- Home

- History

-

Controversies

- Controversies

- Is John Smith's account of his rescue by Pocahontas true?

- Did John Smith misunderstand a Powhatan 'adoption ceremony'?

- What was the relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith?

- Is it possible that John Smith never actually met Pocahontas?

- Was Smith's gunpowder accident actually a murder plot?

- How should we view John Smith's credibility overall?

- How was Pocahontas captured?

- Did Pocahontas willingly convert to Christianity?

- What should we make of Smith's "rescues" by so many women?

- Were Pocahontas and John Rolfe in love?

- What was the meaning of Pocahontas's final talk with John Smith?

- How did Pocahontas die?

- How did John Rolfe die?

- Was there a Powhatan prophecy?

- Why didnt the Indians wipe out the settlers?

- When did the balance of power shift from the Powhatans to the English?

- How big a part did European diseases play in the Jamestown story?

- Books

- Art

- Films

- Powhatan Tribes

- Links

- Site Map

- Contact

How should we view John Smith's credibility overall?

While the general credibility of John Smith is an important issue for the understanding of the Pocahontas story, it is also a question that I'm hesitant to tackle. Historians, writers and armchair quarterbacks have debated Smith's veracity for centuries, and I feel eminently unqualified to attempt a definitive answer. As I've done with some of the other questions on this site, I'll throw some information at the wall and we'll see what sticks. This page should be viewed, as a long-term project that will have additions over time.

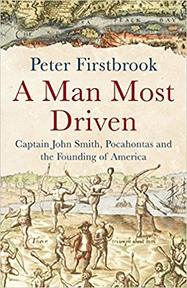

As one means of assessing John Smith's general credibility, I will attempt a complete list of every instance I can find where John Smith's life may have been in mortal danger. The idea here is that these exciting, near-death experiences are what give Smith's life a mythical, adventure story quality that suggest embellishment or even fiction. The majority of these instances are based on Smith's own claims, but we know that there are a number of incidents where the risk to Smith's life was not in dispute. We should remember that Smith, a soldier, sailor and explorer, had many more opportunities to face danger than the average farmer or tradesman. That said, many of the instances on the list cannot be verified, so it's anyone's guess as to whether or not they really happened. There were believers and skeptics in Smith's own lifetime, and more of both in the centuries that followed. [I am relying on Peter Firstbrook's 2014 book, A Man Most Driven: Captain John Smith, Pocahontas and the Founding of America, for events and chronology. I hope to later corroborate these events against Smith's own writings.]

I will also attempt a list of every encounter John Smith had with Indians to try and determine (from Smith's own writings, unfortunately) how fairly or brutally Smith interacted with the Native Americans.

As one means of assessing John Smith's general credibility, I will attempt a complete list of every instance I can find where John Smith's life may have been in mortal danger. The idea here is that these exciting, near-death experiences are what give Smith's life a mythical, adventure story quality that suggest embellishment or even fiction. The majority of these instances are based on Smith's own claims, but we know that there are a number of incidents where the risk to Smith's life was not in dispute. We should remember that Smith, a soldier, sailor and explorer, had many more opportunities to face danger than the average farmer or tradesman. That said, many of the instances on the list cannot be verified, so it's anyone's guess as to whether or not they really happened. There were believers and skeptics in Smith's own lifetime, and more of both in the centuries that followed. [I am relying on Peter Firstbrook's 2014 book, A Man Most Driven: Captain John Smith, Pocahontas and the Founding of America, for events and chronology. I hope to later corroborate these events against Smith's own writings.]

I will also attempt a list of every encounter John Smith had with Indians to try and determine (from Smith's own writings, unfortunately) how fairly or brutally Smith interacted with the Native Americans.

Mary C. Fuller paragraph from Voyages in Print: English Travel to America 1576-1624 (1995)

- "Characterizations of Smith as a liar go back to his own lifetime; a letter by George Percy, one of his fellow colonists, asserts that in his writings Smith 'hathe not spared to appropriate many deserts to himselfe which he never performed, and stuffed his relaycons with many falsities and malycyous detractyons.' (41) Thomas Fuller wrote in 1662 that 'such his perils, preservations, dangers, deliverences, they seem to most men above belief, to some beyond truth.' (42) On the American side, Laura Polayni Striker and Bradford Smith see attacks on Smith by John Gorham Palfrey (History of New England, 1858-90) and Henry Adams as part of the ideological aftermath of the Civil War. 'Smith, once scorned as a fellow without gentle birth, now ironically became the symbol of Southern honor. Northern historians attacked him as a way of undermining the South's symbol of itself, Southern historians defended him. (43) Alexander Brown exhibited striking animus against Smith in his important documentary collection, The Genesis of the United States, casting doubt on virtually every moment of Smith's autobiography and characterizing hims as ' incapable' of telling the truth. (44) Doubt centered particularly around two areas of Smith's narratives: his claim to have been rescued from death by Pocahontas, and the Hungarian and Turkish adventures narrated in True Travels (1630). Striker and Smith say of True Travels that 'with their account of single combat, near death on the battlefield, and a life of slavery in Turkey, these pages had raised scholarly eyebrows for many a year' (477). Documentary research by Striker, Smith and Philip Barbour has verified many of the details of True Travels, and Smith's account of his mock-execution and rescue now seem plausible; (45) yet it is an index of the controversy's vigor that Leo Lemay's 1991 American Dream of Captain Smith makes defense of Smith's honesty into one of its minor themes. (46)" p. 103, 104

Peter Firstbrook' A Man Most Driven: Captain John Smith, Pocahontas and the Founding of America (2014)

Peter Firstbrook' A Man Most Driven: Captain John Smith, Pocahontas and the Founding of America (2014)

Biographer Peter Firstbrook's assessment of John Smith's truthfulness

"The only European witness to [Smith's alleged rescue by Pocahontas] was Smith himself, and his account has been questioned ever since it was first published in 1624. If the only debatable episode in Smith's extraordinary life was this encounter with Pocahontas, then his version of events might not have attracted quite so much attention -- or derision. But this was not the case." A Man Most Driven, p. 4

"Smith's autobiography, The True Travels, Adventures and Observations of Captain John Smith, is packed full of the most incredible incidents: that he fought, defeated and beheaded three enemy commanders in duels' that he was sold into slavery, only to murder his master and escape; that he was captured by pirates, survived shipwrecks and marched up to the gallows to be hanged -- only to be reprieved at the last moment. All this happened, or so John Smith claimed, even before he met Pocahontas and her father." p. 4

"Smith left many diaries and memoirs of his astonishing exploits, but which of his more fanciful claims are the writings of a deceitful self-publicist -- and which are anchored in the historical record?" p. 5

"Throughout all this debate, the fundamental question has remained: can John Smith be relied on to be an honest writer and historian, or is his record so fraught with uncertainties that he cannot - and should not - be trusted?" p. 357

Speaking only of events in and around Jamestown, Firstbrook says that for the most part, Smith's activities were documented and generally corroborated (or apparently not disputed) by other writers among the settlers, such as Percy, Archer, Wingfield and Ratcliffe. Each person's account differed in some details, but no one actively disputed Smith's accounts, though they rarely gave him credit for any successes either.

Firstbrook gives the example of Smith's 1609 incident on the Pamunkey River, when he and his men were surrounded by 700 Indians led by Opechancanough. Smith told of taking Opechancanough at gunpoint and forcing the Indians to give the colonists corn and allow them to return to Jamestown. George Percy, who was present with the group, never wrote about this amazing encounter, which is suspicious. However, Percy was no fan of Smith, and it's possible he chose not to contribute to Smith's legacy. The event was later corroborated by Michel and Wil Phettiplace, who had also been present, when they mentioned the incident in a verse they wrote that appeared in the third volume of The Generall Historie. (Firstbrook, p. 280, 281) [One wonders if Smith may have influenced their memory of the story.] However, there is no record of Percy disputing Smith's own version of the event, and he was alive and would have certainly read about it. [Can we be sure, though, that any rebuttal by Percy has actually survived to be evaluated?]

"Yet where Smith's testimony can be challenged in the details, his writing mostly stands up to intensive scrutiny. It is therefore reasonable to say he was generally accurate, candid and reliable, and that his writings are a vital firsthand history of his period." Firstbrook, p. 359

Speaking of Smith's earlier years, when he traveled alone in Europe and Russia, Firstbrook acknowledges that details are impossible to validate. Smith's writings show some inconsistencies with other contemporary accounts, but overall his "... writings show a remarkable understanding of this very complex and complicated period in the region." p. 358. Smith clearly miss-spoke when he claimed both his parents had died when he was 13, as his mother survived another 3 years. Today, this seems like a serious error, but the writing style of the 16th century would have made allowances for this. Smith may have been hoping to win the compassion of the reader, or he may have considered the detail inconsequential so many years later when he wrote of it. (Firstbrook, p. 359)

My comment on Firstbrook's conclusion:

I am in general agreement that Smith's firsthand accounts of his Jamestown exploits seem reliable, with allowances for puffery and self-congratulation. An exception would be of the Pocahontas rescues, which were added later to the general story, and deserve ample skepticism, as I've pointed out elsewhere on this site. I find more to doubt about Smith's European exploits, particularly when he claims to have made several military innovations. Ultimately, though, it is nearly impossible to say for sure which incidents are true, somewhat true, or simply false. We just have to take everything with a grain of salt.

"The only European witness to [Smith's alleged rescue by Pocahontas] was Smith himself, and his account has been questioned ever since it was first published in 1624. If the only debatable episode in Smith's extraordinary life was this encounter with Pocahontas, then his version of events might not have attracted quite so much attention -- or derision. But this was not the case." A Man Most Driven, p. 4

"Smith's autobiography, The True Travels, Adventures and Observations of Captain John Smith, is packed full of the most incredible incidents: that he fought, defeated and beheaded three enemy commanders in duels' that he was sold into slavery, only to murder his master and escape; that he was captured by pirates, survived shipwrecks and marched up to the gallows to be hanged -- only to be reprieved at the last moment. All this happened, or so John Smith claimed, even before he met Pocahontas and her father." p. 4

"Smith left many diaries and memoirs of his astonishing exploits, but which of his more fanciful claims are the writings of a deceitful self-publicist -- and which are anchored in the historical record?" p. 5

"Throughout all this debate, the fundamental question has remained: can John Smith be relied on to be an honest writer and historian, or is his record so fraught with uncertainties that he cannot - and should not - be trusted?" p. 357

Speaking only of events in and around Jamestown, Firstbrook says that for the most part, Smith's activities were documented and generally corroborated (or apparently not disputed) by other writers among the settlers, such as Percy, Archer, Wingfield and Ratcliffe. Each person's account differed in some details, but no one actively disputed Smith's accounts, though they rarely gave him credit for any successes either.

Firstbrook gives the example of Smith's 1609 incident on the Pamunkey River, when he and his men were surrounded by 700 Indians led by Opechancanough. Smith told of taking Opechancanough at gunpoint and forcing the Indians to give the colonists corn and allow them to return to Jamestown. George Percy, who was present with the group, never wrote about this amazing encounter, which is suspicious. However, Percy was no fan of Smith, and it's possible he chose not to contribute to Smith's legacy. The event was later corroborated by Michel and Wil Phettiplace, who had also been present, when they mentioned the incident in a verse they wrote that appeared in the third volume of The Generall Historie. (Firstbrook, p. 280, 281) [One wonders if Smith may have influenced their memory of the story.] However, there is no record of Percy disputing Smith's own version of the event, and he was alive and would have certainly read about it. [Can we be sure, though, that any rebuttal by Percy has actually survived to be evaluated?]

"Yet where Smith's testimony can be challenged in the details, his writing mostly stands up to intensive scrutiny. It is therefore reasonable to say he was generally accurate, candid and reliable, and that his writings are a vital firsthand history of his period." Firstbrook, p. 359

Speaking of Smith's earlier years, when he traveled alone in Europe and Russia, Firstbrook acknowledges that details are impossible to validate. Smith's writings show some inconsistencies with other contemporary accounts, but overall his "... writings show a remarkable understanding of this very complex and complicated period in the region." p. 358. Smith clearly miss-spoke when he claimed both his parents had died when he was 13, as his mother survived another 3 years. Today, this seems like a serious error, but the writing style of the 16th century would have made allowances for this. Smith may have been hoping to win the compassion of the reader, or he may have considered the detail inconsequential so many years later when he wrote of it. (Firstbrook, p. 359)

My comment on Firstbrook's conclusion:

I am in general agreement that Smith's firsthand accounts of his Jamestown exploits seem reliable, with allowances for puffery and self-congratulation. An exception would be of the Pocahontas rescues, which were added later to the general story, and deserve ample skepticism, as I've pointed out elsewhere on this site. I find more to doubt about Smith's European exploits, particularly when he claims to have made several military innovations. Ultimately, though, it is nearly impossible to say for sure which incidents are true, somewhat true, or simply false. We just have to take everything with a grain of salt.

Firstbrook's assessment of Smith's achievements and legacy

"Some of Smith's achievements are beyond dispute, most especially his success in saving the Jamestown settlement in Virginia during its first two brutal winters. The surviving settlers recognized that Smith had exercised his skill and experience to help them survive. But he was also a difficult and argumentative man, and he clashed constantly with his fellow colonists. One leader of the colony called Smith 'an ambitious, unworthy, and vainglorious fellow'." A Man Most Driven,, p. 5 [Quote within quotes attributed to George Percy, 1612]

"Centuries later, this reputation lived on. Rather than being universally lauded for saving England's first permanent settlement in the Americas -- which ultimately let to North America becoming part of the English-speaking world -- Smith was vilified, maligned and pilloried. Was he really such a villain? Or might he be the victim of envy, internal division and misrepresentation, both in his own day and in the historical record?" p. 5

"Captain John Smith would probably claim there should be more to the assessment of his life than just his writings. He was a tough, fit, resilient man who survived and even thrived on privation, hardship and arduous conditions. He endured illnesses, injuries and accidents that would have killed most men several times over. If he were alive today, he might claim that his greatest contribution to history came not from his writings, but from his performance as a soldier and leader ..." p. 359

"Smith saw action in several military campaigns: the war in the Low Countries, perhaps also in Ireland, certainly in Eastern Europe, at sea in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, and of course in North America. He gained mettle on the battlefield and at the council table, but he was not without fault. Indeed, he made several tactical mistakes during his time in Jamestown, not least by sailing up the Pamunkey River during the drought stricken winter of 1608 in search of food, instead of warning the settlers back in Jamestown of the duplicity of Wahunsenacawh and the danger this posed to the colony. He was also undoubtedly arrogant, testy and difficult." p. 360

"Yet he was more competent and better experienced than most, if not all, of his contemporaries in Virginia. Good leadership was severely lacking in those early years of the colony, and Smith's tenure as a dissident rebel and later as an authoritarian president most likely saved the settlement. Had it not been for Smith's vision, bloody-minded determination and guile, Jamestown would almost certainly have been added to the list of abandoned English colonies, along with Roanoke (1590), Cuttyhunk Island (1602), and Popham (1608)." p. 360

"Smith's turbulent years in Jamestown have cast his achievements in New England in the shade. Although he spent only a short summer surveying the coast from Monhegan Island to Cape Cod, his charts and writings laid a foundation for a different style of settlement in the Americas for decades to come. In New England, Smith saw the opportunity for an individual to create a new life through determination and hard work, in a union of equals. Here a man could be free from the social shackles that had constrained him from birth." p. 363

"After his voyage to New England, Smith became single-minded in his promotion of the colonization of the Americas. Six years later, using his charts and sailing directions, the Pilgrims settled in Plymouth, and put in practice his vision for a new society in the New World. Over the next four centuries, millions of people followed in their footsteps." p. 363

My comments on Firstbrook:

Firstbrook has presumably spent uncountable hours immersed in the writings of John Smith as well as in the research of other Smith scholars, and I find his assessments of Smith to be fair and restrained. No definitive answer about Smith's credibility is offered, but I feel comfortable in this view of his legacy and in the importance of Smith as one of America's "founding fathers." As usual, the Powhatan Indians are given little credit for their role in keeping the Jamestown settlement alive, but given their simultaneous (and eminently reasonable) efforts to dislodge the colonists, I realize that Firstbrook would have had difficulty fitting their contribution into this John Smith narrative. (Certainly Firstbrook wrote about them, but we don't come away thinking of the Powhatans as being among the "founding fathers", not that they would want to be viewed as such. I have heard grumblings, however, that they are never given credit for their contributions.)

"Some of Smith's achievements are beyond dispute, most especially his success in saving the Jamestown settlement in Virginia during its first two brutal winters. The surviving settlers recognized that Smith had exercised his skill and experience to help them survive. But he was also a difficult and argumentative man, and he clashed constantly with his fellow colonists. One leader of the colony called Smith 'an ambitious, unworthy, and vainglorious fellow'." A Man Most Driven,, p. 5 [Quote within quotes attributed to George Percy, 1612]

"Centuries later, this reputation lived on. Rather than being universally lauded for saving England's first permanent settlement in the Americas -- which ultimately let to North America becoming part of the English-speaking world -- Smith was vilified, maligned and pilloried. Was he really such a villain? Or might he be the victim of envy, internal division and misrepresentation, both in his own day and in the historical record?" p. 5

"Captain John Smith would probably claim there should be more to the assessment of his life than just his writings. He was a tough, fit, resilient man who survived and even thrived on privation, hardship and arduous conditions. He endured illnesses, injuries and accidents that would have killed most men several times over. If he were alive today, he might claim that his greatest contribution to history came not from his writings, but from his performance as a soldier and leader ..." p. 359

"Smith saw action in several military campaigns: the war in the Low Countries, perhaps also in Ireland, certainly in Eastern Europe, at sea in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, and of course in North America. He gained mettle on the battlefield and at the council table, but he was not without fault. Indeed, he made several tactical mistakes during his time in Jamestown, not least by sailing up the Pamunkey River during the drought stricken winter of 1608 in search of food, instead of warning the settlers back in Jamestown of the duplicity of Wahunsenacawh and the danger this posed to the colony. He was also undoubtedly arrogant, testy and difficult." p. 360

"Yet he was more competent and better experienced than most, if not all, of his contemporaries in Virginia. Good leadership was severely lacking in those early years of the colony, and Smith's tenure as a dissident rebel and later as an authoritarian president most likely saved the settlement. Had it not been for Smith's vision, bloody-minded determination and guile, Jamestown would almost certainly have been added to the list of abandoned English colonies, along with Roanoke (1590), Cuttyhunk Island (1602), and Popham (1608)." p. 360

"Smith's turbulent years in Jamestown have cast his achievements in New England in the shade. Although he spent only a short summer surveying the coast from Monhegan Island to Cape Cod, his charts and writings laid a foundation for a different style of settlement in the Americas for decades to come. In New England, Smith saw the opportunity for an individual to create a new life through determination and hard work, in a union of equals. Here a man could be free from the social shackles that had constrained him from birth." p. 363

"After his voyage to New England, Smith became single-minded in his promotion of the colonization of the Americas. Six years later, using his charts and sailing directions, the Pilgrims settled in Plymouth, and put in practice his vision for a new society in the New World. Over the next four centuries, millions of people followed in their footsteps." p. 363

My comments on Firstbrook:

Firstbrook has presumably spent uncountable hours immersed in the writings of John Smith as well as in the research of other Smith scholars, and I find his assessments of Smith to be fair and restrained. No definitive answer about Smith's credibility is offered, but I feel comfortable in this view of his legacy and in the importance of Smith as one of America's "founding fathers." As usual, the Powhatan Indians are given little credit for their role in keeping the Jamestown settlement alive, but given their simultaneous (and eminently reasonable) efforts to dislodge the colonists, I realize that Firstbrook would have had difficulty fitting their contribution into this John Smith narrative. (Certainly Firstbrook wrote about them, but we don't come away thinking of the Powhatans as being among the "founding fathers", not that they would want to be viewed as such. I have heard grumblings, however, that they are never given credit for their contributions.)

A different take; Rountree less enthusiastic about Smith

As Firstbrook above is mainly positive about Smith, I think I should present another side. Helen C. Rountree (who is not Native American, by the way) is an anthropologist and recognized expert on the Powhatan Indians I'll present her thoughts here, I am a little doubtful that Rountree's understanding of Smith matches her understanding of the Powhatans, though, as she has been wrong when relating the story of how Smith supposedly told of multiple rescues by beautiful women. Rountree may not have been the first to do this, but numerous historians who followed her took her word for it. This is unfortunate, so read my take on that here. Anyway, here's Rountree on Smith's reliability:

As Firstbrook above is mainly positive about Smith, I think I should present another side. Helen C. Rountree (who is not Native American, by the way) is an anthropologist and recognized expert on the Powhatan Indians I'll present her thoughts here, I am a little doubtful that Rountree's understanding of Smith matches her understanding of the Powhatans, though, as she has been wrong when relating the story of how Smith supposedly told of multiple rescues by beautiful women. Rountree may not have been the first to do this, but numerous historians who followed her took her word for it. This is unfortunate, so read my take on that here. Anyway, here's Rountree on Smith's reliability:

- "Historians have a standard against which to measure accounts of past events: an account is more likely to be reliable if it is written by a neutral party very soon after the events described in it. Thus letters home, if they are not self-justifying ones, are more trustworthy than later accounts written for the public, especially self-aggrandizing accounts written many years later. That comparison encapsulates the writings of Captain John Smith, who stayed in Virginia between only April 1607 and September 1609. Smith's 1608 True Relation was a report sent home to an unknown person and quickly published without the writer's knowledge. Virginia's native people appear in the narrative as unknown quantities, which they were to Europeans at the time: people who were potentially either friendly or hostile. Smith's "Map of Virginia," written in 1612, was a factual account of the Powhatans' way of life, but it was followed by a history, the "Proceedings of the English Colony, that was produced with his approval by several friends and composed for public consumption during a period in which the Jamestown colony was expanding successfully. The Powhatans appear as formidable adversaries but not monstrous ones. Yet the time lapse and the story's tendency to upgrade Smith and downgrade the colony's other leaders should make a skeptic's radar go off occasionally. Smith wrote his Generall Historie in 1624, adding to the "Proceedings" and taking the story onward during a period of vicious war with the Powhatans that often led Smith, who was unwillingly on the shelf, to say, "I told you so!" The Powhatans appear repeatedly in that work as unpredictable and murderous, when they are not cowering with fear at Smith's bravado. The one shining exception—in 1607-9 --is Pocahontas, who is given a much-inflated role for a prepubescent female child in her culture. When we read some passages, the radar is screaming now.

All of the writers from Jamestown had the general biases of men of their time: they thought English culture was superior; they considered women, English or Powhatan, to be weak and inferior; and they were uninterested in personalities and motivations (those are twentieth-century concepts). But their accounts can be used, with the same caveats about timing and audience to corroborate or disprove Smith's versions of things. For that reason, the writings of George Percy, Gabriel Archer, and Edward Maria Wingfield are useful, even though they detested Smith personally: very often they back up his early writings about the native people's actions." - Rountree, Helen C. from Pocahontas, Powhatan, Opechancanough: Three Indian Lives Changed by Jamestown (2005), p. 1, 2

A list of times John Smith was (or may have been) in a life or death situation (as per Firstbrook via Smith, 2014)

* John Smith was most likely born in early January of 1580 (some sources say he was baptized Jan. 6, others say Jan. 9.)

More to come ...

* John Smith was most likely born in early January of 1580 (some sources say he was baptized Jan. 6, others say Jan. 9.)

- Although neither Smith nor Firstbrook mentioned it, the fact that Smith survived childhood was something of an accomplishment. According to one 17th Century statistician, 1/3 of children in London never made it past the age of 6. Smith didn't grow up in London, but disease was still a serious issue for every family in Europe in this era, and children were especially vulnerable.

- In 1597 (Firstbrook, p. 25), Smith went off to fight the Spanish in the Low Countries (the Netherlands). Although Smith did not write in detail about his time there, Firstbrook says "there is little doubt Smith saw battle" (p. 26). Firstbrooks says Smith later wrote that he regretted "to have seen so many Christians slaughter one another." (p. 26; citing Smith's The True Travels.)

* Benjamin Woolley in Savage Kingdom (2008), however, says there was a "lull in hostilities" at this time in the Low Countries, so the idea that Smith saw battle there is disputed. (p. 27) - In late 1599, on Smith's voyage to Scotland from France, his boat was shipwrecked on the rocks of Lindisfarne. He got to shore but became ill before making his way to Edinburgh (Firstbrook, p 28, 366).

- At the age (roughly) of 20, while in France, Smith got in a duel with a Monsieur Cursell, a man who, along with 3 others, had relieved Smith of all his possessions during the passage from England. Smith running into him in Brittany was an incredible coincidence and an opportunity for retribution. Although this sword fight appears to be the first specific battle account we know of, Smith managed to defeat his opponent (according to himself), while not actually putting his opponent to death. Firstbrook, p. 39

- In 1600, on a boat from Marseille to Italy (via Toulon), Smith succeeded in sufficiently irritating some Catholic passengers to the point where they threw him overboard. He managed to reach the shore of what he later wrote of as the ‘Isle of St. Mary.’ As it turns out, there is no such island in the vicinity, but biographer Firstbrook believes Smith may have arrived at the peninsula called Saint-John-Cap-Ferat. Firstbrook, p. 40-42.

- In early 1601, while on a ship in the Mediterranean captained by a Frenchman named La Roche, Smith found himself suddenly involved in an attack on a Venetian merchant ship. The two ships exchanged fire, but La Roche emerged the victor. Fifteen of La Roche’s men died, but the survivors, including Smith, shared the lucrative plunder from the sinking Venetian ship. p. 44, 45.

- Smith claimed (summer 1601) to have been involved as a mercenary in military activity at the Turkish siege of "Olumpagh" (so named by Smith). His activities in battle are unknown, but he wrote about his contributions in tactics (signalling "Lord Ebersbaught" and hatching a ruse involving lighting thousands of weapon fuses at night to deceive the Turkish forces about how many soldiers they had ready for battle). The Ottomans were defeated, and according to Smith, his actions led to him being promoted to captain of cavalry and command of 250 men. Firstbrook, p. 54-56

- In Sept. 1601, Smith, then a mercenary officer for the Duke of Mercoeur, was involved in the siege and attack on the the walled city of Alba Regalis in (now) western Hungary. Smith tells of making (inventing?) pyrotechnic grenades for use in this attack, which the soldiers, using slings, tossed over the walls. On Sept. 20, Mercoeur's forces breached the city's walls, and Smith wrote, “... it was taken perforce, with such merciless execution, as was most pitiful to behold.” p. 62, 63 from Firstbrook, citing True Travels, Vol. 3, p. 165.

[Comment: By this point, Smith is only 21 years of age, but his life story is already kind of amazing, if true. He's already had to swim to shore from two ships to save his life, and he has (by his own account) devised unusual battle tactics on two separate occasions. However, if we sort of put those incidents on the shelf (assuming they are suspect) and look only at the more believable aspects of his life, we can say with some confidence that he's already a veteran soldier who knows the rigors of military camps and long marches, followed by battle. He has experienced fighting on several occasions, and witnessed the deaths of thousands of soldiers and horses. He's seen cities totally destroyed and plundered. Whatever else you want to say about him, he was probably a legitimately tough dude. Firstbrook went to some trouble to try and verify some of the details of Smith's account. He found that Smith correctly described Mercoeur's movements after they parted ways, which means either that he researched the information (which could not have been an easy task in those days) or he knew of them through their mutual contacts. Place names and some geographical locations could not be verified, but Firstbrook had some reasonable explanations for those.] - Firstbrook (via Smith's own writings) wrote that in the winter of 1602, Smith and his battalion marched through snow and bitter cold to Transylvania. Smith recorded that three or four hundred of his men (out of 6,000) froze to death at night (maybe even a single night!) on the way. Firstbrook notes that the winter of 1601-02 was the coldest in 600 years due to a South American volcano eruption (unknown to Smith, of course). Whether you wish to put this 400 mile march together in a list of 'near-death' experiences or not is debatable, but again, we can say that Smith survived a tough time. p. 69, 70.

- While as a captain in the forces of the Count of Modrusch, which had recently switched sides to support Sigismund Bathory, Prince of Transylvania, in their fight against "roaming bands of mercenaries" (p. 74) the Hajduk, Smith claimed to have been involved in ambushes and skirmishes. In one assault initiated by the Hajduk, Smith noted 1,500 casualties on both sides. (p. 78) It's not clear exactly what part Smith played in the fighting or how much danger he was in here.

- Following the battle above, the Modrusch forces began a siege of a Hajduk fortress that stretched over several months. As a result of boredom, the Hajduk proposed a truce and a duel, with each side supplying a soldier to fight in a jousting match to the death. According to Smith, his own name was drawn by lot to fight against the Hajduk's chosen warrior. (Smith described the battle in The True Travels, p. 172, or see excerpt below). The two warriors wore steel armor and rode their horses toward each other while carrying 40 lb. lances. Smith:s lance pierced the Turk through a gap in his helmet armor, and after his opponent fell to the ground, Smith completed the man's execution with a coup de grace. He severed the head and presented it to his commander, General Mozes Szekely, to the cheers of his fellow soldiers. (Firstbrook, p. 79-81.)

- A friend of the fallen soldier (Grualgo) issued a challenge to Smith to fight again the next day, which Smith accepted. Apparently, the lances of both soldiers broke in the clash. The two men then fired pistols at each other, with a bullet glancing off Smith's armor, and Smith's bullet hitting his opponent in the arm. The Hajduk Turk fell to the ground, and Smith decapitated him, his second victory in two days. He took his enemy's horse and armor as spoils. p. 81.

- Full of confidence after two victories, Smith issued the next challenge, which was accepted by a Hajduk soldier named Bonny Mulgro. Mulgro had the choice of weapon and selected pistols and battle-axes on horseback. .They both fired and missed in their first attempt. Smith was forced off his horse by blows from his opponent, and he dropped his axe. Mulgro approached for the kill, but Smith still had his sabre, which he used to pierce the man's body between plates in his armor. Smith finished him off, and thus took his third head in as many days, or so he claimed. (Firstbrook, p. 81, 82).

[Comment: In the reading I've done so far about John Smith, authors seem to take issue with the Pocahontas rescue most, and then the additional 'rescues' by various women (Lady Tragabigzanda, etc.), but somehow the three duels to the death get a pass, or else they are lumped in with the general doubts about Smith's entire life. I'm not saying I believe or don't believe these duels happened, but they would seem to be candidates for doubt. Firstbrook devotes several paragraphs to the question. (p. 84, 85]. He points out that the story of the duels is similar to those in "The Famous and Pleasant History of Parismus, the Valiant and Renowned Prince of Bohemia," (1598-99) by Emanuel Ford. However, Firstbrook also points out that there were in fact "trials of arms" on battlefields in those days. Firstbrook also mentions that the location of Regall, where the encounters supposedly took place, has never been identified. Firstbrook says the incident of the three duels is at present "not proven".] - Within weeks of Smith's third duel, and with spirits high, Modrusch's forces breached the defenses of the Hajduk ultimately overwhelming them and putting them to the sword. Firstbrook reckons hundreds, perhaps thousands died in the assault. Firstbrook wrote that many died on the Modrusch side as well, so we can assume that Smith's life was in danger in this battle. p. 83

- Forces under the command of General Szekely, after the victory above, were said to move up the Mures River and sack three more enemy strongholds. We don't know what role Smith may or may not have had in these battles. p. 83

- Under the command of Radul Serban, and in a battle with the forces of Simion Movila, Smith wrote of 25,000 dead in a "bloudy massacre" in which his own side was victorious but battered. p. 92

- While being pursued by an Ottoman force, the forces under Modrusch, of which Smith was a part, took shelter in an isolated wood at night. Smith, according to his own account, proposed fixing a "flammable mixture" to their lances and charging the horses of the enemy, allowing them to break through their encirclement. (Firstbrook makes clear that he is not 100% convinced of this particular story.) p. 92, 93

- In the following days, being pursued by Modrusch's forces, Smith's side dug foxholes and set pointed stakes in the ground to harass enemy cavalry. (Smith claimed the enemy numbered 40,000.) Smith's side survived the initial assault and supposedly mangled many enemy horses and slew their riders. (This and #19 below may be called the Battle of Rottenton.) p. 94

- The Ottoman enemy regrouped and pursued their assault of Modrusch's forces. Smith was one of apparently 30,000 casualties left on the field. He was wounded and unable to move, though we don't know exactly what his injuries were. Modrusch was able to escape with about 1,300 or 1,400 cavalry, though it's unclear how Smith would know this. p. 94. Firstbrook appears to have doubts about this battle, as there is no confirming record of it. However, he wonders why Smith would invent a story of being left incapacitated on the battlefield. p. 98

- Pillagers circulated among the wounded and dead on the battlefield, taking what they could and killing those who still lived. By virtue of Smith's coat of arms and clothing, the pillagers thought Smith might merit a ransom and allowed him to live. They nursed him back to health, though it's not clear in Firstbrook's account that Smith's captors ever actually tried to ransom him. p. 95

- Smith apparently survived a 200 mile march in chains to the Ottoman slave market at Axiopolis (now Cernavoda, Romania). p. 98

- Smith was purchased in the slave market by a man named Bashaw Bogall and marched in chains to Constantinople. p.100

[According to Smith's account, he was assigned to work for Bogall's mistress, Charatza Tragabigzanda, in what would seem to be a rather cushy assignment as her servant. They were apparently able to communicate in Italian. p. 102. She had Smith for a while, then sent him off to work for her brother, "the Tymor Bashaw of Natbrits" p. 102] - Smith was forced to work on a farm, harvesting and separating grain. Smith's master (the brother of Tragabigzanda) treated him cruelly, and Smith managed to kill him with his threshing bat and escape on the man's horse. p. 107

[Smith survived a 16-day journey on horseback to "Muscovia" with the little corn he had taken and was treated kindly by the governor of Aecopolis and by Lady Callamata. p. 108, 109 He then made the 3-month trip back to Transylvania to seek out Sigismund Bathory to recover his coat of arms, which had been lost when he was sold into slavery. He apparently got the papers he needed and some money (1,500 gold ducats). p. 111] After traveling around Germany, France and Spain,Smith went to Morocco and gave a credible (according to Firstbrook) account of his time there. p. 112, 13] - Smith reported meeting a French Captain Merham, on whose boat he was forced by a storm to head for the Canaries. While on that boat, Merham, a pirate, boarded three ships and took what he could. We don't know if Smith was involved in the pirating, but presumably this was a dangerous activity. p. 114.

- Merham's ship was pursued by two Spanish ships and became involved in a 2-day battle at sea. A reported 27 members of Merham's crew were killed, and both ships were damaged. Smith apparently didn't write of his own involvement (if any) in the fighting. Somehow they made it back to Morocco, and then Smith returned to England near the end of 1604 (age 23). p. 115, 116

[Little is known about the time Smith spent in England after his return from Africa and before his departure for Virginia., Firstbrook speculates he may have spent time in Ireland, England's only colony at the time, and a common destination for English soldiers. Edward Maria Wingfield is quoted as having insulted Smith about his behavior in Ireland: "It was proved to his face, that he begged in Ireland like a rogue, without lycence." [9]. However, Firstbrook notes that Wingfield would not himself have been in Ireland at that time. p. 126, 127] - On the voyage to Virginia, Smith managed to antagonize the other passengers (most of all, Wingfield and Percy, according to Firstbrook) and thrown in the brig on charges of mutiny. A charge of mutiny is serious, and he could have been executed at any time, but he made it intact to the Caribbean. Smith claimed that a gallows was built for him on the island of Nevis, but that he was somehow reprieved and re-imprisoned. p. 148-154. Even after his name was revealed to be on the list of seven councilors to govern the new colony, Smith remained in confinement. p. 164.

[The newly arrived colonists in Virginia had several interactions with the Indians, but Smith had no part in these, being still imprisoned. He was not allowed to take his place on the council due to the charges of mutiny. He was not allowed to vote for who would be governor, the result being that Wingfield was elected. As the colonists made preparations to make shelters and defenses, all hands were needed and at this time, it appears that Smith made his reappearance to help with unloading and construction. p. 167-176.] - Smith made his first contact with the Powhatan Indians when he was chosen by Capt. Newport to be part of a crew of 23 men to explore upriver in a first attempt to seek a passage to the South Seas and to look for gold or other minerals. Firstbrook speculates that Smith was chosen to be part of this crew because he was an experienced soldier and in order to put some space between Smith and Wingfield. The expedition put them in contact with the Weyanock, with 8 unspecified Indians in the company of Navirans (Nauriraus), then with the Arrohattoc, and then with Parahunt, a son of Powhatan. Though there is no indication these meetings were particularly dangerous or on the verge of violence, they took place while Jamestown was under attack unbeknownst to this group. As the crew of 23 was outnumbered and arrows were flying elsewhere, a wrong move during this voyage could have put Smith's and the others' lives in danger. p. 179, 180; p. 184, 185.

- In the aftermath of the attack, in which two died, the colonists built a palisade for defense. The Indians tested the fort's defense and killed at least two more. In the months that followed, and after Newport had left with his crew for re-supply, many more settlers died of disease and foul water. Smith also became ill, but he recovered. Roughly half of the remaining colonists died of disease and famine. p. 190.

[Wingfield had been deposed as president of the council and Ratcliffe, with Smith's cooperation, named instead. Smith was named "supply officer" and for organizing work details in the fort. With the surviving colonists unwilling or unable to work hard for their own survival, Smith took it upon himself to seek food from the Indians. (p. 200-202).} - On Smith's first excursion as "supply officer," Smith took a few men in a shallop to the Kecoughtan village to barter for food. Because the Indians there offered so little in return for a hatchet, Smith surmised they had evaluated Smith's group as being desperate. If this is true, there may have been some danger to Smith and his men, though we have no indication they were threatened by the Kecoughtan. However, on the return journey to Jamestown, Smith says they were approached by two canoes from "another village" (p. 203), and in the version he told of this encounter in 1624, they were attacked by an outnumbering force. Smith's men succeeded in repulsing the attack with their muskets and chasing the Indians ashore and into the woods. An Indian counter-attack occurred, which was again repulsed. The two groups then somehow made peace and traded to the benefit of both parties. (p. 204). There appears to have been no English casualties in this encounter, though it should be counted as a dangerous event, assuming it were true. There appears to be some doubt about that, though, by writers and historians (p. 204).

[Smith subsequently went on an unspecified number of trading missions, any of which could be regarded as dangerous, but in the absence of specific information by Smith or others, I won't include them in this list as 'life or death' situations. Firstbrook notes that Smith regarded the Paspahegh as being "churlish and treacherous" (p. 204) and prone to attempts at theft of guns and swords. Smith also made several excursions up the Chickahominy River, where he had much success in procuring corn. Relations with the Chickahominy tribe in these early excursions seem to have been peaceful (p. 205).

In early December of 1607, the situation at Jamestown had become dire under the governance of Ratcliffe. A blacksmith, James Read, was nearly executed for attacking Ratcliffe, but he was spared when he fingered George Kendall as a spy and conspirator against the governing body. Kendall was executed, and Wingfield, Ratcliffe and others lobbied for abandoning the colony and making for England in the small boat they had, the Discovery. John Martin and John Smith opposed the idea, and shots were fired, apparently resulting in no deaths. The colonists ultimately agreed to persevere a bit longer (p. 206, 207). While the state of affairs in Jamestown at this time could arguably be described as dangerous to Smith, I won't include it as a 'life or death' situation.

Still in December, Ratcliffe sent Smith and 9 men up the Chikahominy River to look for a passage to Asia. The group went some 50 miles up the river, but further progress was blocked by a fallen tree. Smith returned 10 miles downstream to the village of Apokant. There he asked the villagers to lend him two guides and a canoe to take him further upstream. He took two colonists with him, Thomas Emry, a carpenter. and John Robinson, a gentleman. The remaining seven colonists in the party were to remain with the shallop. They soon disobeyed this order when they were enticed to shore by some Indian women, and they fell into an ambush by Indian warriors. All of the colonists made it back to the shallop except one, the laborer George Casson, who was captured and tortured to death, apparently in view of the men on the shallop (p. 207, 208)] - Unaware of the incident above, Smith and his party of two Indian guides and two colonists proceeded upriver and passed the fallen tree that had earlier blocked their progress. They went ashore to rest and eat. After eating, Smith took one guide on foot to hunt for more food, leaving the two colonists with the other Indian at the canoe with orders to fire their muskets if there was a problem. Fifteen minutes later, Smith heard distant hollering, but no warning shot. He put his pistol to the head of his guide. He was then struck in the thigh by an arrow. Smith fired at his attackers, and as many as five Indians fired arrows at Smith, somehow missing him. Smith wrote that he was then surrounded by some 200 armed warriors (p. 208).

- Smith, holding close to his guide and trying to use him as a shield, attempted to make his way back to the canoe. They stumbled into a muddy swamp, however, and were unable to proceed. Surrounded by warriors, Smith threw his pistol into the mud and surrendered to the Indians. Amazingly, he was not immediately killed (p. 208).

- The warriors took Smith back to the canoe, where he saw Robinson dead with 20 or 30 arrows in him. Thomas Emry was not there. Smith was taken to the leader of the warriors, Opechancanough, a roughly 60-year-old Pamunkey weroance and the younger brother of Powhatan. Smith attempted to pique the man's interest by showing him a compass, hoping the mysterious north-pointing needle would sufficiently fascinate him. In his excitement, he also began a monologue about the movement of planets and stars in the night sky. Apparently unimpressed, the warriors tied Smith to a tree and stood ready to shoot him with their arrows. Opechancanough, however, decided to spare Smith, thinking perhaps that Smith could be useful to them as a hostage. Smith was then taken to a lodge and allowed to eat. (p. 207, 208).

- Over the course of several weeks, Smith was marched from village to village within the Powhatan confederacy. He reported being bound and released many times and "at each place I expected when they would execute me" (Firstbrook p. 210, citing A True Relation). During this time, Smith was apparently well fed and exchanged information and disinformation with his captors..It was during this tour that Smith claimed to have been on the verge of execution at the command of Powhatan only to be rescued by his daughter, Pocahontas. Two pages (1, 2) on this website are devoted to the controversy surrounding the supposed rescue, but however one chooses to view the 'rescue', there should be no doubt that Smith's life was in the balance during this period. One member of Smith's party had been tortured to death, and another shot full of arrows. That a similar fate didn't befall Smith was due to luck, Smith's bearing as a leader, and the unpredictable deliberations of the Powhatans. Even after Smith was released and sent back to Jamestown with warrior escorts, he continued to expect "every houre to be put to death" (Firstbrook, p. 225, citing A True Relation).

- After arriving 'safely' at Jamestown, and after not providing the warrior escorts with the guns they required as a condition of his release, Smith immediately found himself in a quarrel with John Ratcliffe and John Archer. who now wished to take the Discovery and sail back to England. Smith said he would fire on the boat should they attempt to leave, but Ratcliffe and Archer challenged Smith and charged him with the deaths of Robinson and Emry, who had been under Smith's care on the excursion up the Chickahominy River. Their judgement was that Smith was to be hanged the next day. Amazingly, Captain Newport's supply ship arrived that very night, saving Smith from the noose. Though many doubt Smith's many stories of cheating death, this time there was corroboration: Wingfield's writings backed Smith up: "... I believe his hanging [was to have been] the same or the next daie, so speedie is our lawe thear, but it pleased God to send Captayn Newport unto us the same eevening, to our unspeakable comfortes; whose arryval saved Master Smyth's leif and myne ..." (Firstbrook, p. 227).

[Newport freed Smith and reappointed him to his position on the ruling council. Firstbrook emphasizes that a few hours delay in Newport's arrival, an earlier release of Smith by Powhatan, or a decision by Smith's warrior escorts to not stop for the night en route to Jamestown all could have resulted in the premature death of John Smith (p. 227).]

More to come ...

Peter Firstbrook, in A Man Most Driven (2014), tells us that shortly after Smith's death, a Welsh clergyman named David Lloyd published a satire (The Legend of Captaine Jones, 1631*) that parodied Smith's writings, Firstbrook says the satire was so successful that it was reprinted numerous times over the next 40 years, and was likely more popular than Smith's own account. Lloyd even wrote a sequel in 1648 to take advantage of his success (p. 354).

The Legend of Captain Jones is available for free at The Internet Archive. * Firstbrook uses the spelling 'Captaine,' but the Internet Archive image from a 1671 publication shows the spelling 'Captain.' Below is an excerpt from the title page.

The Legend of Captain Jones is available for free at The Internet Archive. * Firstbrook uses the spelling 'Captaine,' but the Internet Archive image from a 1671 publication shows the spelling 'Captain.' Below is an excerpt from the title page.

|

The legend of Captain Jones: : the first and second part. Relating his adventure to sea: his first landing, and strange combat with a mighty bear. His furious battel with his six and thirty men against the army of eleven kings, with their overthrow and deaths. His relieving of Kemper castle. His strange and admirable sea-fight with six huge gallies of Spain, and nine thousand souldiers. His being taken prisoner, and hard usage. His being set at liberty by the kings command, and return for England. Also, his other incredible adventures and atchievements by sea and land; continued to his death

by Lloyd, David, 1597-1663 From The Internet Archive (accessed Jan. 27, 2018); link to document, The Legend of Captain Jones |

Short Biographies of John Smith

"The Adventures of John Smith," by Ken Ringle, March 11, 1998 (The Washington Post)

"Captain John Smith," by Bill Warder, June 2009 (Historic Jamestowne)

"Soldier of Fortune: John Smith Before Jamestown," by Meredith Hindley, Jan./Feb. 2007 (Humanities)

"John Smith (bap. 1580-1631)" by Martha McCartney at Virginia Encyclopedia

Also ...

"Our Town: Four centuries on, the battles over John Smith and Jamestown still rage" The New Yorker article (2007), by Jill Lepore

"The Adventures of John Smith," by Ken Ringle, March 11, 1998 (The Washington Post)

"Captain John Smith," by Bill Warder, June 2009 (Historic Jamestowne)

"Soldier of Fortune: John Smith Before Jamestown," by Meredith Hindley, Jan./Feb. 2007 (Humanities)

"John Smith (bap. 1580-1631)" by Martha McCartney at Virginia Encyclopedia

Also ...

"Our Town: Four centuries on, the battles over John Smith and Jamestown still rage" The New Yorker article (2007), by Jill Lepore

John Smith's account of 3 duels with Turks (1602) from The True Travels, Adventures, and Observations of Captain John Smith into Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, excerpt from Chap. VII, at Project Gutenberg

|

The next day Zachel Moyses, General of the Army, pitched also his Tents with nine thousand Foot and Horse, and six and twenty Pieces of Ordnance; but in regard of the Situation of this strong Fortress, they did neither fear them nor hurt them, being upon the point of a fair Promontory, environed on the one side within half a Mile with an un-useful Mountain, and on the other side with a fair Plain, where the Christians encamped, but so commanded by their Ordnance, they spent near a Month in entrenching themselves, and raising their Mounts to plant their Batteries; which slow proceedings the Turks oft derided, that their Ordnance were at pawn, and how they grew fat for want of Exercise, and fearing lest they should depart ere they could assault their City, sent this Challenge to any Captain in the Army.

That to delight the Ladies, who did long to see some Court-like pastime, the Lord Turbashaw did defie any Captain, that had the command of a Company, who durst Combate with him for his Head: The matter being discussed, it was accepted, but so many Questions grew for the undertaking, it was decided by Lots, which fell upon Captain Smith, before spoken of. Truce being made for that time, the Rampires all beset with fair Dames, and Men in Arms, the Christians in Battalia; Turbashaw with a noise of Haut-boys entred the Field well mounted and armed; on his shoulders were fixed a pair of great Wings, compacted of Eagles Feathers, within a ridge of Silver, richly garnished with Gold and precious Stones, a Janizary before him, bearing his Lance, on each side another leading his Horse; where long he stayed not, ere Smith with a noise of Trumpets, only a Page bearing his Lance, passing by him with a courteous Salute, took his Ground with such good success, that at the sound of the charge, he passed the Turk thorow the sight of his Beaver, Face, Head and all, that he fell dead to the Ground, where alighting and unbracing his Helmet, cut off his Head, and the Turks took his Body; and so returned without any hurt at all. The Head he presented to the Lord Moyses, the General, who kindly accepted it, and with joy to the whole Army he was generally welcomed. The Death of this Captain so swelled in the Heart of one Grualgo, his vowed Friend, as rather inraged with madness than choler, he directed a particular challenge to the Conqueror, to regain his Friends Head, or Idle his own, with his Horse and Armour for advantage, which according to his desire, was the next day undertaken: as before upon the sound of the Trumpets, their Lances flew in pieces upon a clear Passage, but the Turk, was near unhorsed. Their Pistols was the next, which marked Smith upon the Placard; but the next shot the Turk, was so Wounded in the left Arm, that being not able to rule his Horse, and defend himself, he was thrown to the ground, and so bruised with the fall, that he lost his Head, as his Friend before him, with his Horse and Armour; but his Body, and his rich Apparel were sent back to the Town. Every day the Turks made some Sallies, but few Skirmishes would they endure to any purpose. Our Works and Approaches being not yet advanced to that heighth and effect, which was of necessity to be performed; to delude time, Smith with so many incontradictible perswading Reasons, obtained leave, that the Ladies might know he was not so much enamoured of their Servants Heads; but if any Turk, of their rank would come to the place of Combate to redeem them, should have his also upon the like conditions, if he could win it. The challenge presently was accepted by Bonny Mulgro. The next day, both the Champions entring the Field as before, each discharging their Pistol, having no Lances, but such martial Weapons as the Defendant appointed, no hurt was done; their Battle-Axes was the next, whose piercing Bills made sometime the one, sometime the other to have scarce sense to keep their Saddles, specially the Christian received such a blow, that he lost his Battle axe, and failed not much to have fallen after it, whereat the supposed conquering Turk, had a great shout from the Rampires. The Turk, prosecuted his advantage to the uttermost of his power; yet the other, what by the readiness of his Horse, and his judgement and dexterity in such a business, beyond all Mens expectation, by God's assistance, not only avoided the Turks violence but having drawn his Faulchion, pierced the Turk, so under the Culets, thorow back and body, that altho' he alighted from his Horse, he stood not long ere he lost his Head, as the rest had done. |

On the portrayal of John Smith in James A. Michener's Chesapeake

James Michener (1907-1997) was a best-selling author who researched locales around the globe, investigating their history and culture, and then wrote "historical" novels that drew on the events that transpired there. Among the locations covered was the Chesapeake area of Virginia and Maryland, and Michener wrote a multi-generational novel that started with some fictional Choptank Indians circa 1583 and ended in the story of a hurricane in 1978. I'm not a fan of Michener, as I stated on my Books for Adults page, However, I think his portrayal of John Smith, while entirely fictitious, does present a point of view about Smith that should at least be explored. I want to emphasize that Michener's ideas about John Smith are just one person's speculation, and I doubt Michener went very deeply into John Smith's writings in his research, However, I think it may be worthwhile to consider the possibility that Smith embellished his account with details that, while false, created an overall story which reflected a truth as Smith saw it, and possibly a "higher truth", if we're willing to buy into that. Personally, I prefer to stick as much as possible with the historical record about Smith over what we can imagine with no restraint, but I think we may gain a perspective with Michener's portrayal here nonetheless.

Quoting from Chesapeake:

[Again, the above quotes are from a fictional book (Chesapeake) by James A. Michener, and are not actual quotes by John Smith. I include them here as one possible way to view the John Smith record.]

James Michener (1907-1997) was a best-selling author who researched locales around the globe, investigating their history and culture, and then wrote "historical" novels that drew on the events that transpired there. Among the locations covered was the Chesapeake area of Virginia and Maryland, and Michener wrote a multi-generational novel that started with some fictional Choptank Indians circa 1583 and ended in the story of a hurricane in 1978. I'm not a fan of Michener, as I stated on my Books for Adults page, However, I think his portrayal of John Smith, while entirely fictitious, does present a point of view about Smith that should at least be explored. I want to emphasize that Michener's ideas about John Smith are just one person's speculation, and I doubt Michener went very deeply into John Smith's writings in his research, However, I think it may be worthwhile to consider the possibility that Smith embellished his account with details that, while false, created an overall story which reflected a truth as Smith saw it, and possibly a "higher truth", if we're willing to buy into that. Personally, I prefer to stick as much as possible with the historical record about Smith over what we can imagine with no restraint, but I think we may gain a perspective with Michener's portrayal here nonetheless.

Quoting from Chesapeake:

- "[Smith's] buoyancy was remarkable, and when the shallop responded nicely to the wind he cried, 'Fairly launched! It's to be a famous journey!' Steed [a fictitious character and scribe] wrote down these remarks and others on the folded sheets he carried in a canvas bag, and that night he transcribed them into a proper journal, which Captain Smith reached for as soon as it was completed. [p. 74, 75]

He did not like what he saw. He did not like it at all. The geographical facts were accurate enough, but he was chagrined that he should have misjudged Steed's talents by such a margin, and with the forthrightness which characterized him, he broached the subject. 'Mister Steed, at the beginning of our historic journey you have me saying, 'We shall be gone thirty days, and at the end you will wish it had been ninety.' That's a poor speech for the launching of a great adventure.'

'It's what you said, sir.'

'I know. But our time onshore was brief. You must take that into consideration.' And he grabbed the pen from his scribe and sat for some time beneath the swaying lantern, composing a more appropriate opening address:

[Michener then has Smith writing a fictitious inspirational speech as a record for the journal, one which I doubt would have occurred to Smith to make, but then, I can't claim to say I alone know the real John Smith.]

With a flourish, Captain Smith shoved the paper back to his scribe, who held it near the lantern, his blond features betraying the astonishment he felt as he read the captain's corrections.

'You never said those things, Captain.'

'I was thinking them,' Smith snapped. 'Had there been time, I'd have said them.'

Steed was about to protest when he looked into the shadows and saw the bearded face of his little commander. It was like iron edged with oak, and he realized that Smith would have made just such a speech had the occasion permitted, and he sensed that it was not what a soldier said, but what he intended, which provided motivation. John Smith lived intimately with possibilities that other men could not even imagine, and in his dreaming he forced them to become reality." [p.75, 76] - *When they returned to the shallop, [Steed] faced the exacting task of describing this adventure. He wanted to be accurate and to report the placid quality of this Indian village, yet he knew that he must also display Captain Smith in heroic posture, and this was difficult. When the commander read the narrative he could not hide his displeasure. [p. 79]

'You want to name the island Devon? And so it shall be, but would it not be wiser to show in the record that this was my decision, not yours?' [p. 80]

'I merely proposed it, sir. Confirmation is left to you.'

'Confirmed, but I would prefer the record to show that the suggestion came from me, too.'

'It will be noted.'

Then Smith frowned.and pointed to the real trouble. 'You spend too few words on our departure. You must recall, for you were involved, what a risky business we undertook. It is no mean task for three men to go unarmed into the heart of hostile Indian territory.'

Steed was about to say that he had never seen people less hostile, Indian or not, but he deemed it wiser to keep his silence. Passing the pages over to the captain, he held the lantern so that Smith could edit them, and after a while he was handed this:

[Michener then has Smith giving Steed an embellished account in which Smith alone names the aforementioned island Devon and relates their mission with Smith acting conspicuously bravely. I am omitting the text, as well as the previous one above, as I don't want Michener's words to be confused with actual writing by the real, historical John Smith.]

When Steed read this dumbfounding report he did not know where to begin. It was all true, and at the same time totally false. He skipped the part about the naming of Devon Island; Captain Smith commanded, and until he confirmed a name, it had not been given. He was also willing to ignore Smith's claims that the Indians had been hostile; to one so often the victim of Indian guile they might have seemed so. And he was even content to have the giant warrior with the three turkey feathers appear stupid, because the others were. He thought, with some accuracy: Smith hated the clever Choptank because the Indian was so very tall and he so very short. He wanted him to be stupid. [p. 81]

But it did gall the Oxford student to have Smith quoting Machiavelli to inspire his men. 'I heard no Machiavel,' he said cautiously.

'The Indians were pressing, and I had not the time.'

[Again, the above quotes are from a fictional book (Chesapeake) by James A. Michener, and are not actual quotes by John Smith. I include them here as one possible way to view the John Smith record.]

Relevant Documents

- A True Relation by Captain John Smith, 1608 at Virtual Jamestown

- A Description of New England, 1616 (PDF)

- New England's Trials by Captain John Smith, 1620 (rare first edition, PDF)

- The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England and the Summer Isles by Captain John Smith (PDF)

- The Complete Works of Captain John Smith at Virtual Jamestown

- The True Travels, Adventures, and Observations of Captain John Smith into Europe, Asia, Africa, and America at Project Gutenberg .

- All of John Smith's references to Pocahontas (compiled by me on this site; html)

Return to Controversies page

(C) Kevin Miller 2018

Updated August 14, 2022

Updated August 14, 2022

- Home

- History

-

Controversies

- Controversies

- Is John Smith's account of his rescue by Pocahontas true?

- Did John Smith misunderstand a Powhatan 'adoption ceremony'?

- What was the relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith?

- Is it possible that John Smith never actually met Pocahontas?

- Was Smith's gunpowder accident actually a murder plot?

- How should we view John Smith's credibility overall?

- How was Pocahontas captured?

- Did Pocahontas willingly convert to Christianity?

- What should we make of Smith's "rescues" by so many women?

- Were Pocahontas and John Rolfe in love?

- What was the meaning of Pocahontas's final talk with John Smith?

- How did Pocahontas die?

- How did John Rolfe die?

- Was there a Powhatan prophecy?

- Why didnt the Indians wipe out the settlers?

- When did the balance of power shift from the Powhatans to the English?

- How big a part did European diseases play in the Jamestown story?

- Books

- Art

- Films

- Powhatan Tribes

- Links

- Site Map

- Contact