- Home

- History

-

Controversies

- Controversies

- Is John Smith's account of his rescue by Pocahontas true?

- Did John Smith misunderstand a Powhatan 'adoption ceremony'?

- What was the relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith?

- Is it possible that John Smith never actually met Pocahontas?

- Was Smith's gunpowder accident actually a murder plot?

- How should we view John Smith's credibility overall?

- How was Pocahontas captured?

- Did Pocahontas willingly convert to Christianity?

- What should we make of Smith's "rescues" by so many women?

- Were Pocahontas and John Rolfe in love?

- What was the meaning of Pocahontas's final talk with John Smith?

- How did Pocahontas die?

- How did John Rolfe die?

- Was there a Powhatan prophecy?

- Why didnt the Indians wipe out the settlers?

- When did the balance of power shift from the Powhatans to the English?

- How big a part did European diseases play in the Jamestown story?

- Books

- Art

- Films

- Powhatan Tribes

- Links

- Site Map

- Contact

More on the Simon van de Passe Engraving

|

The Simon van de Passe engraving of 1616. For a general introduction to this image and its context with other portraits of Pocahontas, see the main Portraits page. This page will cover certain aspects of the portrait in more detail, namely the inscription, the ostrich feather fan, the beaver hat, the collar, and the artist's skill (or lack thereof) in depicting a Powhatan Indian. An interesting (I hope) addition to this page is in the Inscription section below, where I quote a visitor to this site on the Matoaka vs Matoaks variation. High res image of the Van de Passe engraving on Wikimedia Commons More to come! |

The inscription

There are many sites that show what is written on the engraving, but you will find little analysis of it anywhere. Thankfully, I was provided some valuable new information by a visitor to this website, Jean Fontaine of Quebec (scroll down).

But first, under the portrait in script is the following:

- Ætatis suæ 21. Ao [according to Merriam-Webster, anno ætatis suæ means "in the year of her age", the age being 21; we can assume the Ao (with the 'o' raised) is an abbreviation of anno]

- 1616 [the year the portrait was made; this is our source for Pocahontas being 21 in the year 1616]

- Matoaks als Rebecka daughter to the mighty Prince Powhatan Emperour of Attanoughkomouck als virginia converted and baptized in the Christian faith, and wife to the wor.ff Mr: Joh: Rolff. [Attanoughkomouck is a variation of Tsenacommacah, aka Tsenacomoco, the Powhatan word for what is now Tidewater Virginia; Joh: is an abbreviation of John; Rolff is a variation of Rolfe]

- Si:PaSs:Sculp: [abbreviation of the engraver's name and profession/title, Simon van de Passe Sculptor]

- ComptonHolland excud: [basically, published by Compton Holland. According to Encyclo.co.uk, "excud:" means "He [or she] struck [this]. A printer or engraver's mark, 'made by' [followed by the person's name], used to identify the person who executed, or completed, the work." In this case, the company is named here, though the engraver - Van de Passe - is also named nearby.]

Encircling the portrait in capital letters is the Latin inscription:

- MATOAKA ALS REBECCA FILIA POTENTISS: PRINC: POWHATANI IMP: VIRGINIÆ. [This means "Matoaks, also known as Rebecca, daughter of the powerful prince Powhatan of the empire of Virginia]

Now here's the exciting part .... What if Pocahontas's private name was never Matoaka? There is reason to believe that the inscription below the portrait is the actual name, Matoaks, sometimes spelled Matoax, which is phonetically the same. I am printing this here thanks to an observation by a visitor to this website, Jean Fontaine of Quebec. He wrote the following on May 15, 2021 in the contact form of this site:

- " ... when I first saw her 1616 engraved portrait by Simon van de Passe, I assumed that the "MATOAKA" name in the Latin title on the oval frame was simply an ad hoc Latinization of the name "Matoaks" that can be read in the English caption engraved below the portrait, since the whole Latin inscription is basically an abridged translation of the caption. The same way the names "Henry" and "Mary" would, in those days, be Latinized as "HENRICVS" and "MARIA" for the sake of a Latin inscription in a portrait, I assumed that the translator of the caption gave the name "Matoaks" an "-a" ending, which is expected for Latin female names and feminine nouns. It would seem much less probable that the "Matoaks" form in the caption, with its strange "-aks" ending, is an Anglicization of "Matoaka" than the other way around, that is, "Matoaka" being a Latinization of "Matoaks".

Are there earlier instances of the "Matoaka" variant in a non-Latin context?

If not, my uninformed guess would be that the "Matoaks" variant is closer to the original form, and the "Matoaka" Latinized variant was popularized by the 1616 engraving, where the "Matoaks" form is not helped by the fact that it is much less visually striking than the large "MATOAKA" near the sitter's face.

"Matoaks" would also be consistent with the similar sounding "Matoax" variant mentioned elsewhere.

I suppose a search for the earliest instances of each variant would be the only way to try to establish their genealogy." - Jean Fontaine

My comment:

This makes so much sense! I can't believe I haven't seen this anywhere before. Certainly the Matoaks/Matoax spellings appear in some articles, but the Matoaka spelling and pronunciation seems to have taken over as the presumed correct version. I need to research this more, but for now, I'm more comfortable with Matoaks as the actual name rather than Matoaka. Thank you Jean Fontaine!

More to come ...

Neither Matoaks nor Matoaka were used in early chronicler writings prior to publication of the Van de Passe engraving. Inconveniently, the only references to Pocahontas's private name were by Alexander Whitaker, who offered the variation Matoa, and Samuel Purchas, who recorded it as Matokes.

For more information about Pocahontas's names, check the Four Names of Pocahontas page on this website.

- "Sir the Colony here is much better. Sir Thomas Dale our religious and valiant Governour, hath now brough that to passe, which never before could be effected. For by warre upon our enemies, and kinde usage of our friends, he hath brought them to seeke for peace of us, which is made, and they dare not breake. But that which is best, one Pocahuntas or Matoa the daughter of Powhatan, is married to an honest and discreete English Gentleman Master Rolfe, and that after she had openly I2renounced her countrey Idolatry, confessed the faith of Jesus Christ, and was baptized; which thing Sir Thomas Dale had laboured along time to ground in her." - Alexander Whitaker via Ralph Hamor at Virtual Jamestown

- "Samuel Argall in the yeare 1613, affirmed likewise that he found the state of Virginia farre better then was reported. In one voyage they had gotten one thousand and one bushels of corne: they found a slow kinde of Cattell, as bigge as Kinde, which were good meate; and a medicinal sort of earth. They tooke Pokahuntis (Powhatans deerest daughter) prisoner, a matter of good consequence to them, of best to her, by this meanes becoming a Christian, & married to Master Rolfe, an English Gentleman.

Her true Name was Matokes, which they concealed from the English, in a superstitious feare of hurt by the English if her name were knowne: she is now Christened Rebecca." - Samuel Purchas, from Purchas his Pilgrimage, 1617, 3rd Edition.

For more information about Pocahontas's names, check the Four Names of Pocahontas page on this website.

The ostrich feather fan

Various authors have commented on the white ostrich feathers we see in the Van de Passe engraving, and which are also present in the oil painting copies of the engraving.

Rasmussen & Tilton, Pocahontas; Her life and Legend (1994):

Townsend, Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma (2004)::

Gunn Allen, Pocahontas: Medicine Woman Spy Entrepreneur Diplomat (2003)

As we see, the top two references describe the ostrich feathers as a symbol of royalty, while the third describes the white feathers as a symbol of Pocahontas's office as "Beloved Woman". Both interpretations could be correct, even simultaneously, but I'd like to look at these suggestions a little more closely.

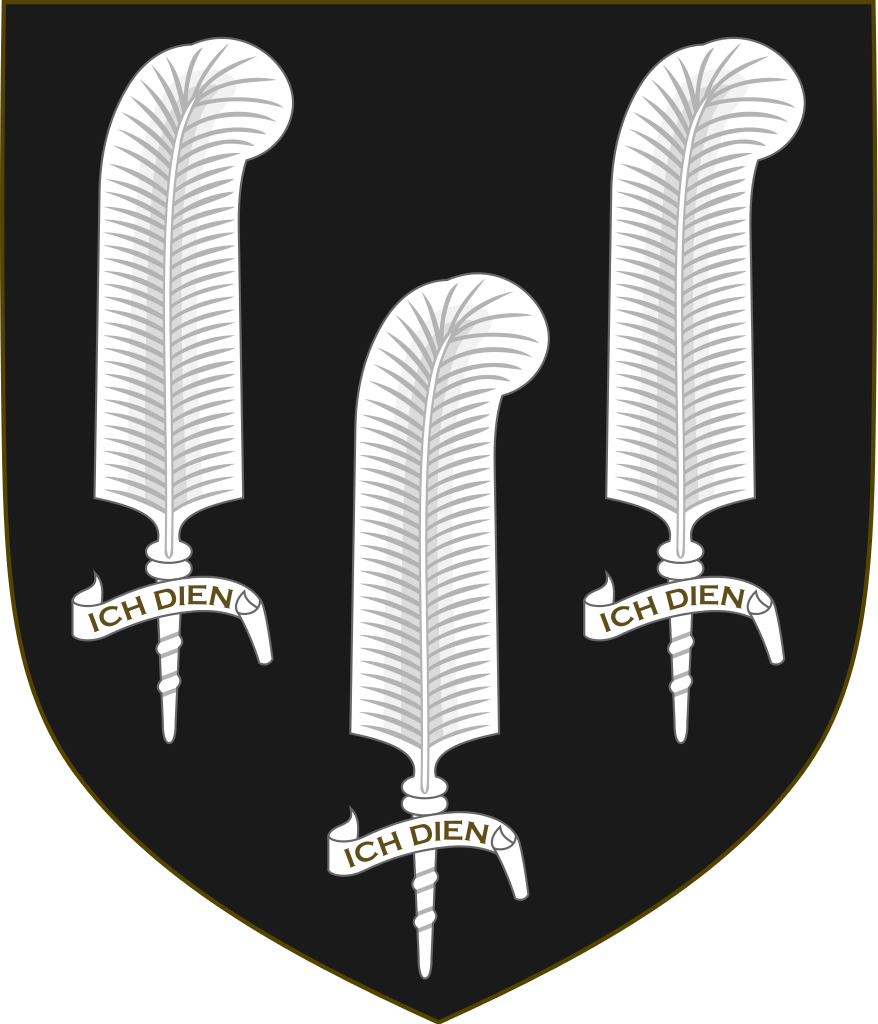

On whether or not ostrich feathers are a symbol of royalty, that appears to be basically true. Ostrich feathers can be seen in the heraldic badge of the Prince of Wales, more specifically, the one that represents Edward the Black Prince (1330-1376). Ostrich feathers continued to be used in badges and emblems by members of the royal family in the 15th Century and beyond.

Various authors have commented on the white ostrich feathers we see in the Van de Passe engraving, and which are also present in the oil painting copies of the engraving.

Rasmussen & Tilton, Pocahontas; Her life and Legend (1994):

- "She holds an ostrich feather, which had long been a symbol of royalty." p. 32

Townsend, Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma (2004)::

- "Long delicate fingers hold a fan of ostrich feathers, a symbol of royalty." p. 152

Gunn Allen, Pocahontas: Medicine Woman Spy Entrepreneur Diplomat (2003)

- "In one hand, a three-plumed white feather fan is propped gracefully, signifying her office as Beloved Woman--a significance perhaps known only to her and the Powhatan members of her party. That she holds this staff of office, as it were, for this formal portrait says much of her self-image and the image she intended to transmit to the English rulers and high society." p. 152

As we see, the top two references describe the ostrich feathers as a symbol of royalty, while the third describes the white feathers as a symbol of Pocahontas's office as "Beloved Woman". Both interpretations could be correct, even simultaneously, but I'd like to look at these suggestions a little more closely.

On whether or not ostrich feathers are a symbol of royalty, that appears to be basically true. Ostrich feathers can be seen in the heraldic badge of the Prince of Wales, more specifically, the one that represents Edward the Black Prince (1330-1376). Ostrich feathers continued to be used in badges and emblems by members of the royal family in the 15th Century and beyond.

Whether the people responsible for arranging the Van de Passe engraving and the outfit Pocahontas wore for it intended the feather fan to be a symbol of royalty, however, is less clear. That is one likely explanation, of course, but the fan could also have been merely a prop or artistic choice. I am inclined to believe it was at least partially an intentional suggestion of royalty for the purpose of emphasizing Pocahontas's status as a "princess", but we'll never know for sure.

With the Gunn Allen reference, there seems to be a suggestion that Pocahontas was making a subversive gesture by holding the white feathers, quietly proclaiming to be a "Beloved Woman". (That the feathers were ostrich obviously would have no significance, since there were no ostriches in America, so Gunn Allen speaks only of the feathers being white.) While I see that this is a possibility, the idea works only if we can assume that Pocahontas chose on her own to hold the feather fan. If so, did she also choose her attire? It's probably more likely that the sitting was arranged, with most details of the portrait meant to fulfill the London Company's mission of propaganda for the Jamestown colony. Pocahontas had probably never had her portrait done before, so she would have likely cooperated with the request to hold an ostrich feather fan. We must also consider the possibility that there was no actual feather fan at all, but that it was added to the image by Van de Passe as an artistic or stylistic embellishment.

Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) really seemed to love having her portrait done, there being hundreds in existence. In many of the portraits, she is not holding anything, but when she is pictured holding something, it is quite often a feathered fan. The center and right fan below are both white ostrich fans, not unlike the fan Pocahontas is seen holding in the Van de Passe engraving. Elizabeth I is also seen with colored feather fans, as in the Darnley portrait at left. Portraits like these would have helped to foster the association of ostrich fans with royalty in the minds of the viewing public, and since they preceded the Van de Passe engraving, we may assume Van de Passe and other prominent portrait artists were well aware of them. That the people who commissioned Pocahontas's portrait hoped to evoke a royal or noble presence by having her hold an ostrich feather fan would not be difficult to imagine.

The beaver hat

I've always been intrigued by the tall beaver hat Pocahontas is wearing in the Van de Passe engraving. There is much to be said about it, but most writers leave it alone. The fur trade, with beaver as a primary objective, changed the lives of North American Indians perhaps more than any other factor, with the exception of old world diseases. Pocahontas could not have foreseen the impact of the fur trade, obviously, but I wonder what her thoughts were of that hat, and did she even realize what she was wearing? How did she acquire it? Did it belong to her, or was it loaned for the portrait? Did she choose to wear it? I have so many questions about it, and very few answers, unfortunately, but I will record here some observations and my limited research on the questions I have.

What color was the beaver hat?

With all the problems in the world, I may be crazy to be concerned about this, but I have always wondered about the color What color was it, and why does it seem to me that most assumptions about it are wrong? The answer, literally, seems to be black or white for most historians and artists, but I have my doubts that either of those are true. You may be reading this for the first time, but in my view, the beaver hat of Pocahontas was neither black nor white, but probably light brown, tan, light gray or cream colored. What follows is information that leads me to that conclusion.

I've always been intrigued by the tall beaver hat Pocahontas is wearing in the Van de Passe engraving. There is much to be said about it, but most writers leave it alone. The fur trade, with beaver as a primary objective, changed the lives of North American Indians perhaps more than any other factor, with the exception of old world diseases. Pocahontas could not have foreseen the impact of the fur trade, obviously, but I wonder what her thoughts were of that hat, and did she even realize what she was wearing? How did she acquire it? Did it belong to her, or was it loaned for the portrait? Did she choose to wear it? I have so many questions about it, and very few answers, unfortunately, but I will record here some observations and my limited research on the questions I have.

What color was the beaver hat?

With all the problems in the world, I may be crazy to be concerned about this, but I have always wondered about the color What color was it, and why does it seem to me that most assumptions about it are wrong? The answer, literally, seems to be black or white for most historians and artists, but I have my doubts that either of those are true. You may be reading this for the first time, but in my view, the beaver hat of Pocahontas was neither black nor white, but probably light brown, tan, light gray or cream colored. What follows is information that leads me to that conclusion.

Black - the default color

There's a reason most artists who used the Van de Passe engraving as a model for their paintings chose to make the hat black. It's because hats in that era that appeared in formal portraits were almost always black (or very dark brown). To be sure, most portraits from the 1600s don't feature hats at all. Women often had elaborate hairstyles, and they usually chose not to cover them, though they sometimes decorated their hair with lace accessories or small white fabric hair coverings. Some men and women did, however, choose to wear a hat. Beaver hats were in fashion, and they were expensive prestige items. A cherished hat may have become an extension of their personality, so they chose to wear a hat in their painted portrait. Some fabric hats, which tend to be sort of flat and shapeless, were light in color, but hats that might be reasonably considered beaver hats were almost always black. I have searched for other colors and have found a few, but the point I'm making here is that if an artist making a painted copy was not sure of the hat color when looking at an engraving, black would certainly be a reasonable choice. Nevertheless, a case can be made that the color of Pocahontas's hat was not black (though not white either).

There's a reason most artists who used the Van de Passe engraving as a model for their paintings chose to make the hat black. It's because hats in that era that appeared in formal portraits were almost always black (or very dark brown). To be sure, most portraits from the 1600s don't feature hats at all. Women often had elaborate hairstyles, and they usually chose not to cover them, though they sometimes decorated their hair with lace accessories or small white fabric hair coverings. Some men and women did, however, choose to wear a hat. Beaver hats were in fashion, and they were expensive prestige items. A cherished hat may have become an extension of their personality, so they chose to wear a hat in their painted portrait. Some fabric hats, which tend to be sort of flat and shapeless, were light in color, but hats that might be reasonably considered beaver hats were almost always black. I have searched for other colors and have found a few, but the point I'm making here is that if an artist making a painted copy was not sure of the hat color when looking at an engraving, black would certainly be a reasonable choice. Nevertheless, a case can be made that the color of Pocahontas's hat was not black (though not white either).

The problem of attempting to deduce color from engravings

Engravers worked in black and white with highlights and shadowing, so colors were left to the imagination of the viewer. Determining colors from these engravings is guesswork at best and compromised by the need of the artist to suggest depth by setting the subject off from the background. Painters who later based their portraits on the Van de Passe engraving were able to choose the colors they imagined, since there is no known written record of what Pocahontas wore for the Van de Passe sitting. All artists saw the lace collar as white, as there are numerous portraits available of similar white lace collars*. The decorative coat has typically been portrayed as being red with gold brocade, though it could just as easily have been green or blue. The beaver hat was often portrayed by artists as being black, since that was the typical color of beaver hats in that era. However, the hat in the engraving appears light and closer to the white of the collar than to the coat, so for at least one artist (Mary Ellen Howe), the hat was pure white. However, I have doubts that her guess was correct. * Note too that not all lace collars were white! See below.

Engravers worked in black and white with highlights and shadowing, so colors were left to the imagination of the viewer. Determining colors from these engravings is guesswork at best and compromised by the need of the artist to suggest depth by setting the subject off from the background. Painters who later based their portraits on the Van de Passe engraving were able to choose the colors they imagined, since there is no known written record of what Pocahontas wore for the Van de Passe sitting. All artists saw the lace collar as white, as there are numerous portraits available of similar white lace collars*. The decorative coat has typically been portrayed as being red with gold brocade, though it could just as easily have been green or blue. The beaver hat was often portrayed by artists as being black, since that was the typical color of beaver hats in that era. However, the hat in the engraving appears light and closer to the white of the collar than to the coat, so for at least one artist (Mary Ellen Howe), the hat was pure white. However, I have doubts that her guess was correct. * Note too that not all lace collars were white! See below.

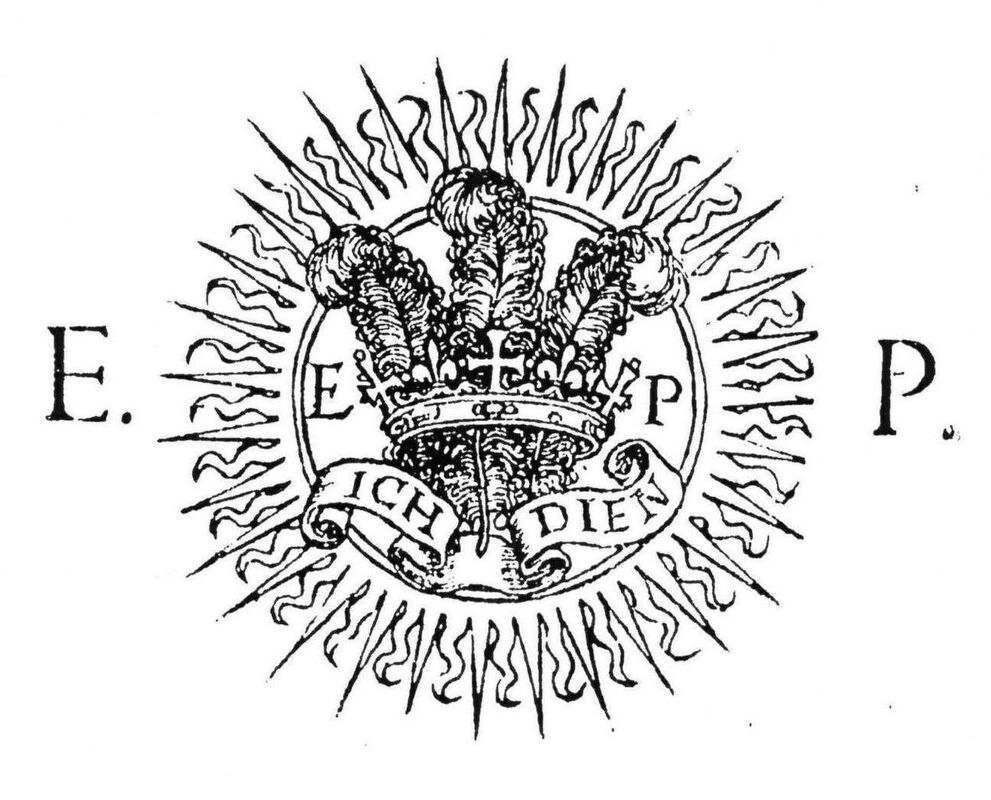

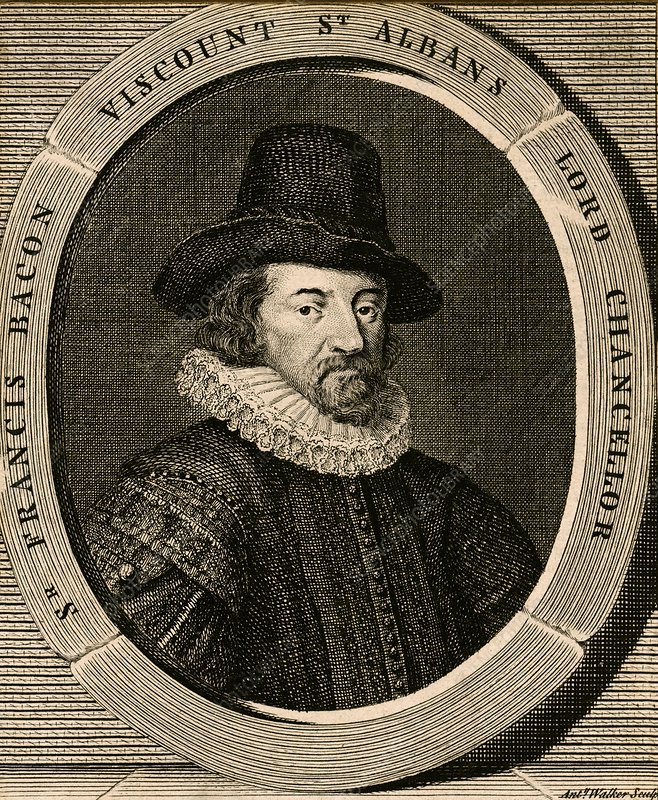

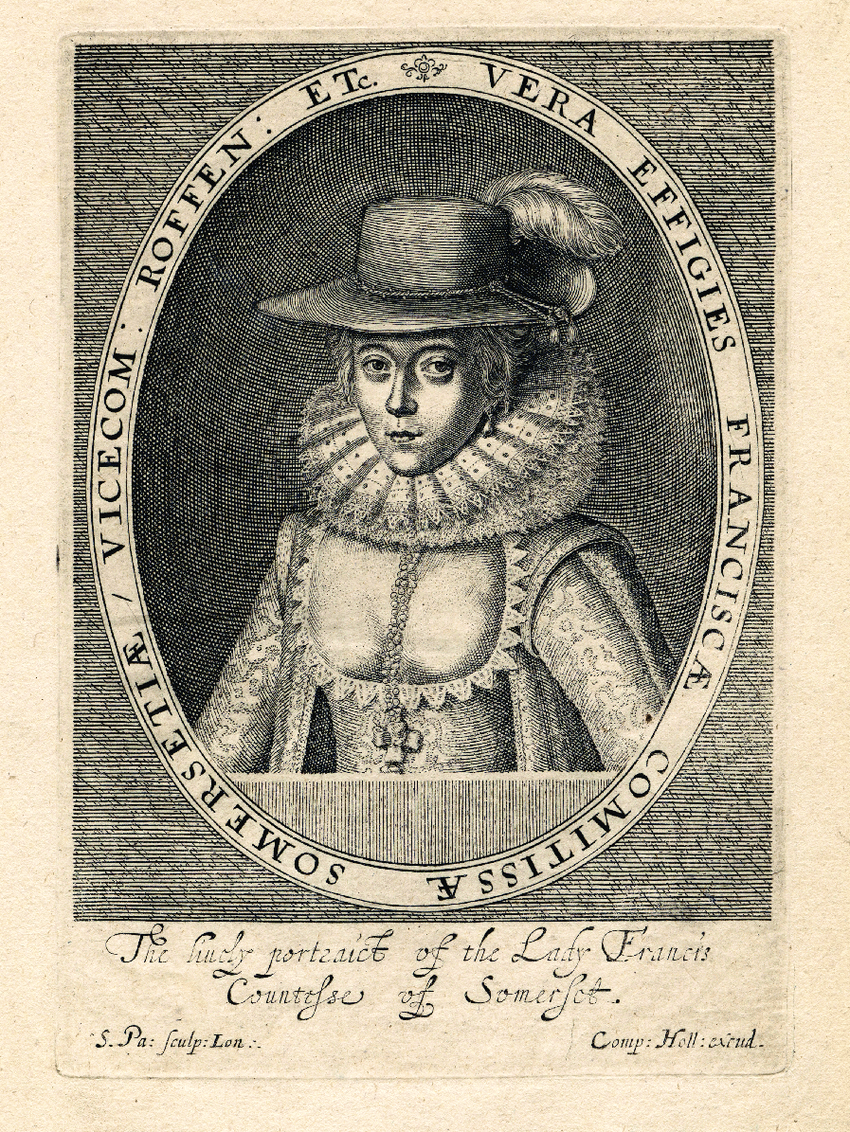

I am not at all an expert on engraving or 17th Century fashion, so I am approaching this topic from a viewpoint of layman's logic. In the engraving of Francis Bacon on the far left, we see a hat that is presumably black, which was the most common color for hats of this type. The second engraving, which is of Lady Frances by Van de Passe, has an ambiguity to it. It's not clearly black, but it might suggest black. We may consider the engraver's need to set the hat off from the background by making it lighter than it actually was. On the other hand, we have to leave open the possibility that the original hat was really brown or gray. The third image is the Van de Passe Pocahontas (1616). Van de Passe had no obligation to maintain consistency between his various engravings, but we might make a guess that he intended the hat to be lighter in color than the Lady Frances one. It could certainly be white as Howe (1994) believes, since it appears no darker than the lace collar, which was likely white (though possibly cream colored). On the other hand, if the hat were light brown, tan, or light gray, would it look any different? Probably not. Lastly, we have the hat of Frederick Hendrick on the far right. Of all the hats shown here, it is the lightest, but can we assume that the engraver meant it to be white? And is his robe also white, like the collar? I don't think so. The vast majority of men in this era wore black hats, so I am of the mind that this engraving is not mean to suggest any particular color. Rather the artist is attempting to put focus on the subject and give it depth by maximizing the contrast with the background. In this case, I think we can assign any color to the hat and clothing that we wish as long as the colors are reasonable for the era. Now, I may be wrong about that, and I welcome any comments or evidence viewers may have to the contrary. So what is the point of this little exercise? To me, based on a comparison of engravings, we can't really determine the color of Pocahontas's hat. A light color is certainly within the realm of possibility, which leaves open choices of white, cream, light gray, tan or light brown. But I am not through with this topic and will make my case that the hat was not pure white.

More to come!

The lace collar

(top row) Pocahontas, by Van de Passe, 1616; Shakespeare (Cobbe Portrait) 1600s; Elizabeth Poulett, by Robert Peake, 1616; Lady Francis Fairfax by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, 1605-1615

(bottom row) Thomas Pope, by William Larkin, 1580-1619; (maybe) Elizabeth Cary, Viscountess Falkland, by Wm. Larkin, 1614-1618; Grey Brydges, by Wm. Larkin, 1615; Frances de Vere, by Wm. Larkin, 1615

The lace collar in the Van de Passe engraving is similar to collars found in some other portraits of the time period. It has a half-oval shape with small leaf-shaped extensions all around the edge. The front edge runs horizontally below the chin, which has the effect of framing the face. The way the collar angles up behind her head has the effect of providing a backdrop to set off the face. I should emphasize that this collar style is just one of many from the time period. We can see that it was in fashion, but there were many other options to choose from at the time.

Lace collars were most often white in 17th Century portraits, but we can see by the bottom row that at least one artist, William Larkin (d. 1619) painted some lace collars of this type in off-white or cream color. Other portraits of his feature white collars, however, so it's unlikely this color was merely a characteristic of the painter. Also, this cream color is not discoloration of the paint, as other parts of the portraits remain white.. I chose to gather these cream-colored collars here to point out that we can't be certain that Pocahontas's collar was white. And if we're not sure the collar was white, then we can't be sure about the hat either.

On Van de Passe's skill (or lack thereof) in depicting a Powhatan Indian

Both Rountree and Townsend commented on Van de Passe's ability to adequately portray a Powhatan Indian. Van de Passe would have had little experience with faces having ethnic features that differed from those of the English and Dutch he lived among. As you can see, Rountree and Townsend had different takes on this aspect of the Van de Passe engraving:

Helen Rountree, Pocahontas, Powhatan and Opechancanough (2005)

Camilla Townsend, Smithsonian Channel (2017) Pocahontas: Beyond the Myth (video):

While researching the Van de Passe engraving, I was fortunate to stumble on another engraving by the same artist of an English woman, Lady Frances, Countess of Somerset. The engraving seems to have been done near in time to the Pocahontas engraving, though there is no clear date. My initial reaction to the Lady Frances image was that it greatly resembled the Pocahontas image, though by looking at it more carefully, I have been able to identify some differences, which I will describe below. I will leave it to the viewer to decide who is more correct, Rountree or Townsend, regarding Van de Passe's skill or lack thereof in depicting a Powhatan Indian.

Both Rountree and Townsend commented on Van de Passe's ability to adequately portray a Powhatan Indian. Van de Passe would have had little experience with faces having ethnic features that differed from those of the English and Dutch he lived among. As you can see, Rountree and Townsend had different takes on this aspect of the Van de Passe engraving:

Helen Rountree, Pocahontas, Powhatan and Opechancanough (2005)

- "That engraving was the only portrait of her done from life, so it is unfortunate that van de Passe was no expert at depicting an Amerind face with epicanthic folds over the eyes."

Camilla Townsend, Smithsonian Channel (2017) Pocahontas: Beyond the Myth (video):

- "It is noteworthy that he did not at that time attempt to make her look like your average white English girl or German girl or French girl, right? She is very clearly in that image a native American person."

While researching the Van de Passe engraving, I was fortunate to stumble on another engraving by the same artist of an English woman, Lady Frances, Countess of Somerset. The engraving seems to have been done near in time to the Pocahontas engraving, though there is no clear date. My initial reaction to the Lady Frances image was that it greatly resembled the Pocahontas image, though by looking at it more carefully, I have been able to identify some differences, which I will describe below. I will leave it to the viewer to decide who is more correct, Rountree or Townsend, regarding Van de Passe's skill or lack thereof in depicting a Powhatan Indian.

Side by side comparison of the faces of Lady Frances and Pocahontas, both by Simon van de Passe, early 1600s

Simon van de Passe likely had more experience depicting men than women during his career. His engraving of John Smith has now become the template for all subsequent images of Smith. Rountree (see above) commented that Van de Passe may have lacked the skill to adequately portray a Native American. Personally, when I first saw the Lady Frances engraving, I wondered if the problem wasn't more that Van de Passe had a limited pallet when portraying women. The eyes and eyebrows seemed to me to be very similar. However, it occurred to me too that a similarity in makeup may have contributed to that effect. I have no definitive answer on that, and I have since identified many differences in the two portraits.

Simon van de Passe likely had more experience depicting men than women during his career. His engraving of John Smith has now become the template for all subsequent images of Smith. Rountree (see above) commented that Van de Passe may have lacked the skill to adequately portray a Native American. Personally, when I first saw the Lady Frances engraving, I wondered if the problem wasn't more that Van de Passe had a limited pallet when portraying women. The eyes and eyebrows seemed to me to be very similar. However, it occurred to me too that a similarity in makeup may have contributed to that effect. I have no definitive answer on that, and I have since identified many differences in the two portraits.

|

Starting from the top:

|

- The eyelids of Lady Frances end more closely at the corners of the eyes, which points to a difference in how Van de Passe depicted the eyelids of the two women. Rountree apparently found Pocahontas's Native American eyelids inadequately represented here, though we can see a difference.

- The eyes of Pocahontas are set slightly wider apart than the eyes of Lady Frances.

- Both images show shadows under the eyes. The shadows of Lady Frances are arguably deeper, but it's difficult to say. Do these shadows reflect sunken eyes, makeup, or neither? Pocahontas has sometimes been described as ill around the time of her portrait sitting, and I have often wondered if that was due to the shadows under her eyes in the engraving. These side by side images, however, reduce that as a possibility (unless both women were ill!)

- The nose of Lady Frances turns up a bit, showing more of her nostrils. We could say that Pocahontas's nose is straighter with less slope, and it's slightly wider at the bridge.

- Lady Frances has puffier cheeks compared to Pocahontas's rather sunken cheeks. This has the effect of accentuating Pocahontas's cheekbones. Later artists chose to reduce that effect in order to make her look more European.

- Pocahontas has a wider mouth, and there is more shadowing at the sides of the upper lip. This could be an effect of the higher cheekbones, or it could indicate a slight overbite.

- Pocahontas has a dimpled chin and a straighter jaw line.

Links to engravings

Francis Bacon, by Anthony Walker, 1700s

https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/608527/view/francis-bacon-english-philosopher

Lady Frances, Countess of Somerset by Van de Passe

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Frances-Countess-of-Somerset-by-Simon-de-Passe-National-Portrait-Gallery-London-D6807_fig3_343764296

Pocahontas, by Van de Passe, 1616

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pocahontas_by_Simon_van_de_Passe_(1616).png

Frederick Hendrick, by Adriaen van de Venne

https://www.wikiart.org/en/adriaen-van-de-venne/portrait-of-frederick-hendrick-prince-of-orange-nassau

National Portrait Galler,y Frances Countess of Somerset

https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp04187/frances-countess-of-somerset

Francis Bacon, by Anthony Walker, 1700s

https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/608527/view/francis-bacon-english-philosopher

Lady Frances, Countess of Somerset by Van de Passe

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Frances-Countess-of-Somerset-by-Simon-de-Passe-National-Portrait-Gallery-London-D6807_fig3_343764296

Pocahontas, by Van de Passe, 1616

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pocahontas_by_Simon_van_de_Passe_(1616).png

Frederick Hendrick, by Adriaen van de Venne

https://www.wikiart.org/en/adriaen-van-de-venne/portrait-of-frederick-hendrick-prince-of-orange-nassau

National Portrait Galler,y Frances Countess of Somerset

https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp04187/frances-countess-of-somerset

(C) Kevin Miller 2019

Updated June 15, 2024

Updated June 15, 2024

- Home

- History

-

Controversies

- Controversies

- Is John Smith's account of his rescue by Pocahontas true?

- Did John Smith misunderstand a Powhatan 'adoption ceremony'?

- What was the relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith?

- Is it possible that John Smith never actually met Pocahontas?

- Was Smith's gunpowder accident actually a murder plot?

- How should we view John Smith's credibility overall?

- How was Pocahontas captured?

- Did Pocahontas willingly convert to Christianity?

- What should we make of Smith's "rescues" by so many women?

- Were Pocahontas and John Rolfe in love?

- What was the meaning of Pocahontas's final talk with John Smith?

- How did Pocahontas die?

- How did John Rolfe die?

- Was there a Powhatan prophecy?

- Why didnt the Indians wipe out the settlers?

- When did the balance of power shift from the Powhatans to the English?

- How big a part did European diseases play in the Jamestown story?

- Books

- Art

- Films

- Powhatan Tribes

- Links

- Site Map

- Contact