|

Charles Dudley Warner (1829-1900) was a 19th Century writer and friend of Mark Twain (see Wikipedia page). His short biography of Pocahontas is posted here because it covers much of the known facts about her as revealed by the original chroniclers and because it's free and public domain. While the writing style and sensibility are very outdated, the account is not terrible or misleading. This biography is actually still being marketed and sold as a paper edition by some publishers. Why buy it when you can read it (legally) here? The actual publication date is something of a mystery (anywhere from 1870-1892?) but I will post the date here if and when I discover it. My quibbles with the account will appear at the bottom of the page (when I get to it).

Also, get Warner's work at Project Gutenberg |

The Story of Pocahontas

Public domain Pocahontas biography by Charles Dudley Warner (1829-1900)

The simple story of the life of Pocahontas is sufficiently romantic without the embellishments which have been wrought on it either by the vanity of Captain Smith or the natural pride of the descendants of this dusky princess who have been ennobled by the smallest rivulet of her red blood.

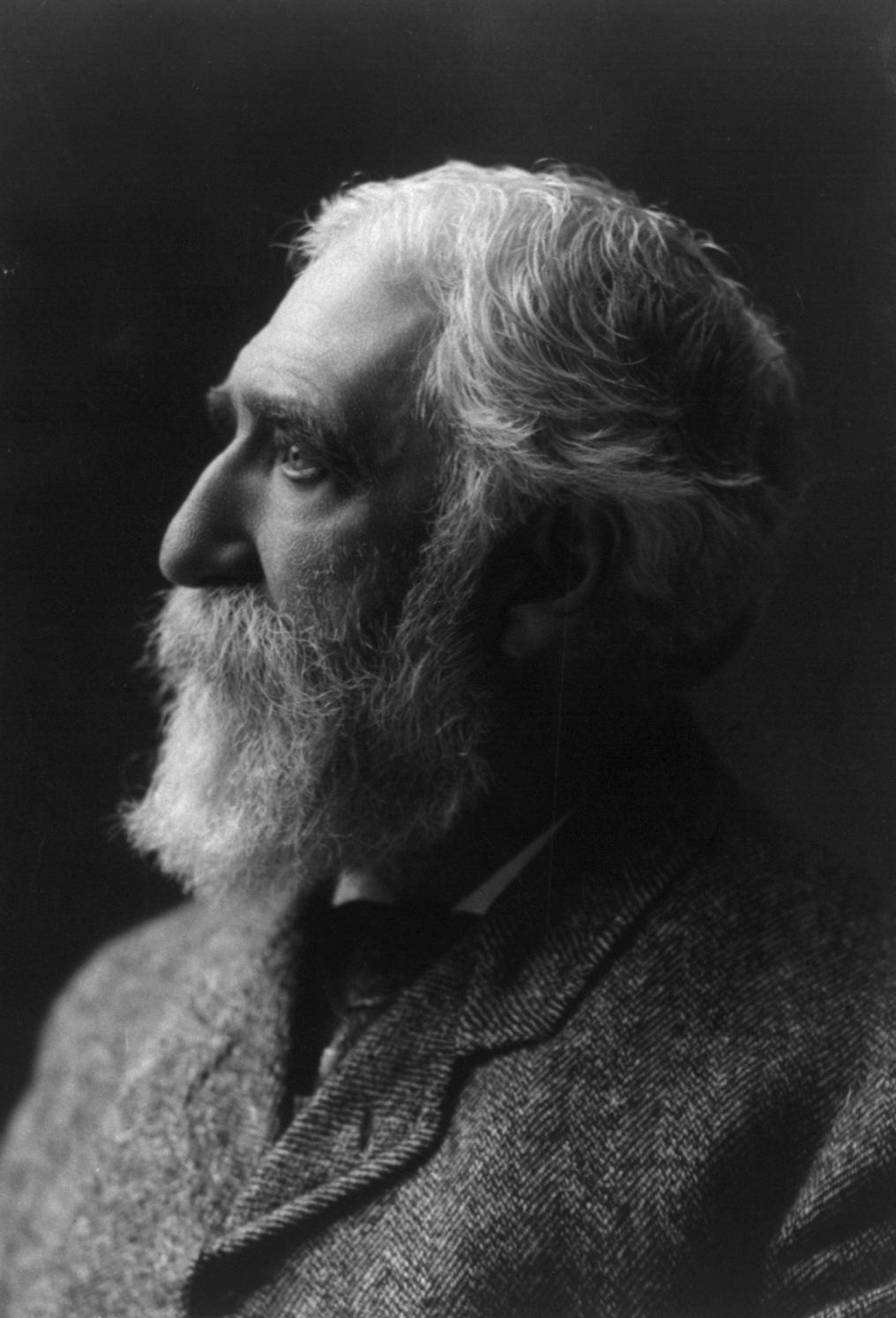

That she was a child of remarkable intelligence, and that she early showed a tender regard for the whites and rendered them willing and unwilling service, is the concurrent evidence of all contemporary testimony. That as a child she was well-favored, sprightly, and prepossessing above all her copper-colored companions, we can believe, and that as a woman her manners were attractive. If the portrait taken of her in London—the best engraving of which is by Simon de Passe—in 1616, when she is said to have been twenty-one years old, does her justice, she had marked Indian features.

The first mention of her is in “The True Relation,” written by Captain Smith in Virginia in 1608. In this narrative, as our readers have seen, she is not referred to until after Smith's return from the captivity in which Powhatan used him “with all the kindness he could devise.” Her name first appears, toward the close of the relation, in the following sentence:

“Powhatan understanding we detained certain salvages, sent his daughter, a child of tenne yeares old, which not only for feature, countenance, and proportion, much exceedeth any of the rest of his people, but for wit and spirit the only nonpareil of his country: this hee sent by his most trusty messenger, called Rawhunt, as much exceeding in deformitie of person, but of a subtill wit and crafty understanding, he with a long circumstance told mee how well Powhatan loved and respected mee, and in that I should not doubt any way of his kindness, he had sent his child, which he most esteemed, to see mee, a Deere, and bread, besides for a present: desiring mee that the Boy [Thomas Savage, the boy given by Newport to Powhatan] might come again, which he loved exceedingly, his little Daughter he had taught this lesson also: not taking notice at all of the Indians that had been prisoners three daies, till that morning that she saw their fathers and friends come quietly, and in good termes to entreate their libertie.

“In the afternoon they [the friends of the prisoners] being gone, we guarded them [the prisoners] as before to the church, and after prayer, gave them to Pocahuntas the King's Daughter, in regard of her father's kindness in sending her: after having well fed them, as all the time of their imprisonment, we gave them their bows, arrowes, or what else they had, and with much content, sent them packing: Pocahuntas, also we requited with such trifles as contented her, to tel that we had used the Paspaheyans very kindly in so releasing them.”

The next allusion to her is in the fourth chapter of the narratives which are appended to the “Map of Virginia,” etc. This was sent home by Smith, with a description of Virginia, in the late autumn of 1608. It was published at Oxford in 1612, from two to three years after Smith's return to England. The appendix contains the narratives of several of Smith's companions in Virginia, edited by Dr. Symonds and overlooked by Smith. In one of these is a brief reference to the above-quoted incident.

This Oxford tract, it is scarcely necessary to repeat, contains no reference to the saving of Smith's life by Pocahontas from the clubs of Powhatan.

The next published mention of Pocahontas, in point of time, is in Chapter X. and the last of the appendix to the “Map of Virginia,” and is Smith's denial, already quoted, of his intention to marry Pocahontas. In this passage he speaks of her as “at most not past 13 or 14 years of age.” If she was thirteen or fourteen in 1609, when Smith left Virginia, she must have been more than ten when he wrote his “True Relation,” composed in the winter of 1608, which in all probability was carried to England by Captain Nelson, who left Jamestown June 2d.

The next contemporary authority to be consulted in regard to Pocahontas is William Strachey, who, as we have seen, went with the expedition of Gates and Somers, was shipwrecked on the Bermudas, and reached Jamestown May 23 or 24, 1610, and was made Secretary and Recorder of the colony under Lord Delaware. Of the origin and life of Strachey, who was a person of importance in Virginia, little is known. The better impression is that he was the William Strachey of Saffron Walden, who was married in 1588 and was living in 1620, and that it was his grandson of the same name who was subsequently connected with the Virginia colony. He was, judged by his writings, a man of considerable education, a good deal of a pedant, and shared the credulity and fondness for embellishment of the writers of his time. His connection with Lord Delaware, and his part in framing the code of laws in Virginia, which may be inferred from the fact that he first published them, show that he was a trusted and capable man.

William Strachey left behind him a manuscript entitled “The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britanica, &c., gathered and observed as well by those who went first thither, as collected by William Strachey, gent., three years thither, employed as Secretaire of State.” How long he remained in Virginia is uncertain, but it could not have been “three years,” though he may have been continued Secretary for that period, for he was in London in 1612, in which year he published there the laws of Virginia which had been established by Sir Thomas Gates May 24, 1610, approved by Lord Delaware June 10, 1610, and enlarged by Sir Thomas Dale June 22, 1611.

The “Travaile” was first published by the Hakluyt Society in 1849. When and where it was written, and whether it was all composed at one time, are matters much in dispute. The first book, descriptive of Virginia and its people, is complete; the second book, a narration of discoveries in America, is unfinished. Only the first book concerns us. That Strachey made notes in Virginia may be assumed, but the book was no doubt written after his return to England.

[This code of laws, with its penalty of whipping and death for what are held now to be venial offenses, gives it a high place among the Black Codes. One clause will suffice:

“Every man and woman duly twice a day upon the first towling of the Bell shall upon the working daies repaire unto the church, to hear divine service upon pain of losing his or her allowance for the first omission, for the second to be whipt, and for the third to be condemned to the Gallies for six months. Likewise no man or woman shall dare to violate the Sabbath by any gaming, publique or private, abroad or at home, but duly sanctifie and observe the same, both himselfe and his familie, by preparing themselves at home with private prayer, that they may be the better fitted for the publique, according to the commandments of God, and the orders of our church, as also every man and woman shall repaire in the morning to the divine service, and sermons preached upon the Sabbath day, and in the afternoon to divine service, and Catechism upon paine for the first fault to lose their provision, and allowance for the whole week following, for the second to lose the said allowance and also to be whipt, and for the third to suffer death.”]

Was it written before or after the publication of Smith's “Map and Description” at Oxford in 1612? The question is important, because Smith's “Description” and Strachey's “Travaile” are page after page literally the same. One was taken from the other. Commonly at that time manuscripts seem to have been passed around and much read before they were published. Purchas acknowledges that he had unpublished manuscripts of Smith when he compiled his narrative. Did Smith see Strachey's manuscript before he published his Oxford tract, or did Strachey enlarge his own notes from Smith's description? It has been usually assumed that Strachey cribbed from Smith without acknowledgment. If it were a question to be settled by the internal evidence of the two accounts, I should incline to think that Smith condensed his description from Strachey, but the dates incline the balance in Smith's favor.

Strachey in his “Travaile” refers sometimes to Smith, and always with respect. It will be noted that Smith's “Map” was engraved and published before the “Description” in the Oxford tract. Purchas had it, for he says, in writing of Virginia for his “Pilgrimage” (which was published in 1613):

“Concerning-the latter [Virginia], Capt. John Smith, partly by word of mouth, partly by his mappe thereof in print, and more fully by a Manuscript which he courteously communicated to mee, hath acquainted me with that whereof himselfe with great perill and paine, had been the discoverer.” Strachey in his “Travaile” alludes to it, and pays a tribute to Smith in the following: “Their severall habitations are more plainly described by the annexed mappe, set forth by Capt. Smith, of whose paines taken herein I leave to the censure of the reader to judge. Sure I am there will not return from thence in hast, any one who hath been more industrious, or who hath had (Capt. Geo. Percie excepted) greater experience amongst them, however misconstruction may traduce here at home, where is not easily seen the mixed sufferances, both of body and mynd, which is there daylie, and with no few hazards and hearty griefes undergon.”

There are two copies of the Strachey manuscript. The one used by the Hakluyt Society is dedicated to Sir Francis Bacon, with the title of “Lord High Chancellor,” and Bacon had not that title conferred on him till after 1618. But the copy among the Ashmolean manuscripts at Oxford is dedicated to Sir Allen Apsley, with the title of “Purveyor to His Majestie's Navie Royall”; and as Sir Allen was made “Lieutenant of the Tower” in 1616, it is believed that the manuscript must have been written before that date, since the author would not have omitted the more important of the two titles in his dedication.

Strachey's prefatory letter to the Council, prefixed to his “Laws” (1612), is dated “From my lodging in the Black Friars. At your best pleasures, either to return unto the colony, or pray for the success of it heere.” In his letter he speaks of his experience in the Bermudas and Virginia: “The full storie of both in due time [I] shall consecrate unto your view.... Howbit since many impediments, as yet must detaine such my observations in the shadow of darknesse, untill I shall be able to deliver them perfect unto your judgments,” etc.

This is not, as has been assumed, a statement that the observations were not written then, only that they were not “perfect”; in fact, they were detained in the “shadow of darknesse” till the year 1849. Our own inference is, from all the circumstances, that Strachey began his manuscript in Virginia or shortly after his return, and added to it and corrected it from time to time up to 1616.

We are now in a position to consider Strachey's allusions to Pocahontas. The first occurs in his description of the apparel of Indian women:

“The better sort of women cover themselves (for the most part) all over with skin mantells, finely drest, shagged and fringed at the skyrt, carved and coloured with some pretty work, or the proportion of beasts, fowle, tortayses, or other such like imagry, as shall best please or expresse the fancy of the wearer; their younger women goe not shadowed amongst their owne companie, until they be nigh eleaven or twelve returnes of the leafe old (for soe they accompt and bring about the yeare, calling the fall of the leaf tagnitock); nor are thev much ashamed thereof, and therefore would the before remembered Pocahontas, a well featured, but wanton yong girle, Powhatan's daughter, sometymes resorting to our fort, of the age then of eleven or twelve yeares, get the boyes forth with her into the markett place, and make them wheele, falling on their hands, turning up their heeles upwards, whome she would followe and wheele so herself, naked as she was, all the fort over; but being once twelve yeares, they put on a kind of semecinctum lethern apron (as do our artificers or handycrafts men) before their bellies, and are very shamefac't to be seene bare. We have seene some use mantells made both of Turkey feathers, and other fowle, so prettily wrought and woven with threeds, that nothing could be discerned but the feathers, which were exceedingly warme and very handsome.”

Strachey did not see Pocahontas. She did not resort to the camp after the departure of Smith in September, 1609, until she was kidnapped by Governor Dale in April, 1613. He repeats what he heard of her. The time mentioned by him of her resorting to the fort, “of the age then of eleven or twelve yeares,” must have been the time referred to by Smith when he might have married her, namely, in 1608-9, when he calls her “not past 13 or 14 years of age.” The description of her as a “yong girle” tumbling about the fort, “naked as she was,” would seem to preclude the idea that she was married at that time.

The use of the word “wanton” is not necessarily disparaging, for “wanton” in that age was frequently synonymous with “playful” and “sportive”; but it is singular that she should be spoken of as “well featured, but wanton.” Strachey, however, gives in another place what is no doubt the real significance of the Indian name “Pocahontas.” He says:

“Both men, women, and children have their severall names; at first according to the severall humor of their parents; and for the men children, at first, when they are young, their mothers give them a name, calling them by some affectionate title, or perhaps observing their promising inclination give it accordingly; and so the great King Powhatan called a young daughter of his, whom he loved well, Pocahontas, which may signify a little wanton; howbeyt she was rightly called Amonata at more ripe years.”

The Indian girls married very young. The polygamous Powhatan had a large number of wives, but of all his women, his favorites were a dozen “for the most part very young women,” the names of whom Strachey obtained from one Kemps, an Indian a good deal about camp, whom Smith certifies was a great villain. Strachey gives a list of the names of twelve of them, at the head of which is Winganuske. This list was no doubt written down by the author in Virginia, and it is followed by a sentence, quoted below, giving also the number of Powhatan's children. The “great darling” in this list was Winganuske, a sister of Machumps, who, according to Smith, murdered his comrade in the Bermudas. Strachey writes:

“He [Powhatan] was reported by the said Kemps, as also by the Indian Machumps, who was sometyme in England, and comes to and fro amongst us as he dares, and as Powhatan gives him leave, for it is not otherwise safe for him, no more than it was for one Amarice, who had his braynes knockt out for selling but a baskett of corne, and lying in the English fort two or three days without Powhatan's leave; I say they often reported unto us that Powhatan had then lyving twenty sonnes and ten daughters, besyde a young one by Winganuske, Machumps his sister, and a great darling of the King's; and besides, younge Pocohunta, a daughter of his, using sometyme to our fort in tymes past, nowe married to a private Captaine, called Kocoum, some two years since.”

This passage is a great puzzle. Does Strachey intend to say that Pocahontas was married to an Iniaan named Kocoum? She might have been during the time after Smith's departure in 1609, and her kidnapping in 1613, when she was of marriageable age. We shall see hereafter that Powhatan, in 1614, said he had sold another favorite daughter of his, whom Sir Thomas Dale desired, and who was not twelve years of age, to be wife to a great chief. The term “private Captain” might perhaps be applied to an Indian chief. Smith, in his “General Historie,” says the Indians have “but few occasions to use any officers more than one commander, which commonly they call Werowance, or Caucorouse, which is Captaine.” It is probably not possible, with the best intentions, to twist Kocoum into Caucorouse, or to suppose that Strachey intended to say that a private captain was called in Indian a Kocoum. Werowance and Caucorouse are not synonymous terms. Werowance means “chief,” and Caucorouse means “talker” or “orator,” and is the original of our word “caucus.”

Either Strachey was uninformed, or Pocahontas was married to an Indian—a not violent presumption considering her age and the fact that war between Powhatan and the whites for some time had cut off intercourse between them—or Strachey referred to her marriage with Rolfe, whom he calls by mistake Kocoum. If this is to be accepted, then this paragraph must have been written in England in 1616, and have referred to the marriage to Rolfe it “some two years since,” in 1614.

That Pocahontas was a gentle-hearted and pleasing girl, and, through her acquaintance with Smith, friendly to the whites, there is no doubt; that she was not different in her habits and mode of life from other Indian girls, before the time of her kidnapping, there is every reason to suppose. It was the English who magnified the imperialism of her father, and exaggerated her own station as Princess. She certainly put on no airs of royalty when she was “cart-wheeling” about the fort. Nor does this detract anything from the native dignity of the mature, and converted, and partially civilized woman.

We should expect there would be the discrepancies which have been noticed in the estimates of her age. Powhatan is not said to have kept a private secretary to register births in his family. If Pocahontas gave her age correctly, as it appears upon her London portrait in 1616, aged twenty-one, she must have been eighteen years of age when she was captured in 1613 This would make her about twelve at the time of Smith's captivity in 1607-8. There is certainly room for difference of opinion as to whether so precocious a woman, as her intelligent apprehension of affairs shows her to have been, should have remained unmarried till the age of eighteen. In marrying at least as early as that she would have followed the custom of her tribe. It is possible that her intercourse with the whites had raised her above such an alliance as would be offered her at the court of Werowocomoco.

We are without any record of the life of Pocahontas for some years. The occasional mentions of her name in the “General Historie” are so evidently interpolated at a late date, that they do not aid us. When and where she took the name of Matoaka, which appears upon her London portrait, we are not told, nor when she was called Amonata, as Strachey says she was “at more ripe yeares.” How she was occupied from the departure of Smith to her abduction, we can only guess. To follow her authentic history we must take up the account of Captain Argall and of Ralph Hamor, Jr., secretary of the colony under Governor Dale.

Captain Argall, who seems to have been as bold as he was unscrupulous in the execution of any plan intrusted to him, arrived in Virginia in September, 1612, and early in the spring of 1613 he was sent on an expedition up the Patowomek to trade for corn and to effect a capture that would bring Powhatan to terms. The Emperor, from being a friend, had become the most implacable enemy of the English. Captain Argall says: “I was told by certain Indians, my friends, that the great Powhatan's daughter Pokahuntis was with the great King Potowomek, whither I presently repaired, resolved to possess myself of her by any stratagem that I could use, for the ransoming of so many Englishmen as were prisoners with Powhatan, as also to get such armes and tooles as he and other Indians had got by murther and stealing some others of our nation, with some quantity of corn for the colonies relief.”

By the aid of Japazeus, King of Pasptancy, an old acquaintance and friend of Argall's, and the connivance of the King of Potowomek, Pocahontas was enticed on board Argall's ship and secured. Word was sent to Powhatan of the capture and the terms on which his daughter would be released; namely, the return of the white men he held in slavery, the tools and arms he had gotten and stolen, and a great quantity of corn. Powhatan, “much grieved,” replied that if Argall would use his daughter well, and bring the ship into his river and release her, he would accede to all his demands. Therefore, on the 13th of April, Argall repaired to Governor Gates at Jamestown, and delivered his prisoner, and a few days after the King sent home some of the white captives, three pieces, one broad-axe, a long whip-saw, and a canoe of corn. Pocahontas, however, was kept at Jamestown.

Why Pocahontas had left Werowocomoco and gone to stay with Patowomek we can only conjecture. It is possible that Powhatan suspected her friendliness to the whites, and was weary of her importunity, and it may be that she wanted to escape the sight of continual fighting, ambushes, and murders. More likely she was only making a common friendly visit, though Hamor says she went to trade at an Indian fair.

The story of her capture is enlarged and more minutely related by Ralph Hamor, Jr., who was one of the colony shipwrecked on the Bermudas in 1609, and returned to England in 1614, where he published (London, 1615) “A True Discourse of Virginia, and the Success of the Affairs there till the 18th of June, 1614.” Hamor was the son of a merchant tailor in London who was a member of the Virginia company. Hamor writes:

“It chanced Powhatan's delight and darling, his daughter Pocahuntas (whose fame has even been spread in England by the title of Nonparella of Firginia) in her princely progresse if I may so terme it, tooke some pleasure (in the absence of Captaine Argall) to be among her friends at Pataomecke (as it seemeth by the relation I had), implored thither as shopkeeper to a Fare, to exchange some of her father's commodities for theirs, where residing some three months or longer, it fortuned upon occasion either of promise or profit, Captaine Argall to arrive there, whom Pocahuntas, desirous to renew her familiaritie with the English, and delighting to see them as unknown, fearefull perhaps to be surprised, would gladly visit as she did, of whom no sooner had Captaine Argall intelligence, but he delt with an old friend Iapazeus, how and by what meanes he might procure her caption, assuring him that now or never, was the time to pleasure him, if he intended indeede that love which he had made profession of, that in ransome of hir he might redeeme some of our English men and armes, now in the possession of her father, promising to use her withall faire and gentle entreaty; Iapazeus well assured that his brother, as he promised, would use her courteously, promised his best endeavors and service to accomplish his desire, and thus wrought it, making his wife an instrument (which sex have ever been most powerful in beguiling inticements) to effect his plot which hee had thus laid, he agreed that himself, his wife and Pocahuntas, would accompanie his brother to the water side, whither come, his wife should faine a great and longing desire to goe aboorde, and see the shippe, which being there three or four times before she had never seene, and should be earnest with her husband to permit her—he seemed angry with her, making as he pretended so unnecessary request, especially being without the company of women, which denial she taking unkindly, must faine to weepe (as who knows not that women can command teares) whereupon her husband seeming to pitty those counterfeit teares, gave her leave to goe aboord, so that it would pleese Pocahuntas to accompany her; now was the greatest labour to win her, guilty perhaps of her father's wrongs, though not knowne as she supposed, to goe with her, yet by her earnest persuasions, she assented: so forthwith aboord they went, the best cheere that could be made was seasonably provided, to supper they went, merry on all hands, especially Iapazeus and his wife, who to expres their joy would ere be treading upon Captaine Argall's foot, as who should say tis don, she is your own. Supper ended Pocahuntas was lodged in the gunner's roome, but Iapazeus and his wife desired to have some conference with their brother, which was onely to acquaint him by what stratagem they had betraied his prisoner as I have already related: after which discourse to sleepe they went, Pocahuntas nothing mistrusting this policy, who nevertheless being most possessed with feere, and desire of returne, was first up, and hastened Iapazeus to be gon. Capt. Argall having secretly well rewarded him, with a small Copper kittle, and some other les valuable toies so highly by him esteemed, that doubtlesse he would have betraied his own father for them, permitted both him and his wife to returne, but told him that for divers considerations, as for that his father had then eight of our Englishe men, many swords, peeces, and other tooles, which he hid at severall times by trecherous murdering our men, taken from them which though of no use to him, he would not redeliver, he would reserve Pocahuntas, whereat she began to be exceeding pensive, and discontented, yet ignorant of the dealing of Japazeus who in outward appearance was no les discontented that he should be the meanes of her captivity, much adoe there was to pursuade her to be patient, which with extraordinary curteous usage, by little and little was wrought in her, and so to Jamestowne she was brought.”

Smith, who condenses this account in his “General Historie,” expresses his contempt of this Indian treachery by saying: “The old Jew and his wife began to howle and crie as fast as Pocahuntas.” It will be noted that the account of the visit (apparently alone) of Pocahontas and her capture is strong evidence that she was not at this time married to “Kocoum” or anybody else.

Word was despatched to Powhatan of his daughter's duress, with a demand made for the restitution of goods; but although this savage is represented as dearly loving Pocahontas, his “delight and darling,” it was, according to Hamor, three months before they heard anything from him. His anxiety about his daughter could not have been intense. He retained a part of his plunder, and a message was sent to him that Pocahontas would be kept till he restored all the arms.

This answer pleased Powhatan so little that they heard nothing from him till the following March. Then Sir Thomas Dale and Captain Argall, with several vessels and one hundred and fifty men, went up to Powhatan's chief seat, taking his daughter with them, offering the Indians a chance to fight for her or to take her in peace on surrender of the stolen goods. The Indians received this with bravado and flights of arrows, reminding them of the fate of Captain Ratcliffe. The whites landed, killed some Indians, burnt forty houses, pillaged the village, and went on up the river and came to anchor in front of Matchcot, the Emperor's chief town. Here were assembled four hundred armed men, with bows and arrows, who dared them to come ashore. Ashore they went, and a palaver was held. The Indians wanted a day to consult their King, after which they would fight, if nothing but blood would satisfy the whites.

Two of Powhatan's sons who were present expressed a desire to see their sister, who had been taken on shore. When they had sight of her, and saw how well she was cared for, they greatly rejoiced and promised to persuade their father to redeem her and conclude a lasting peace. The two brothers were taken on board ship, and Master John Rolfe and Master Sparkes were sent to negotiate with the King. Powhatan did not show himself, but his brother Apachamo, his successor, promised to use his best efforts to bring about a peace, and the expedition returned to Jamestown.

“Long before this time,” Hamor relates, “a gentleman of approved behaviour and honest carriage, Master John Rolfe, had been in love with Pocahuntas and she with him, which thing at the instant that we were in parlee with them, myselfe made known to Sir Thomas Dale, by a letter from him [Rolfe] whereby he entreated his advice and furtherance to his love, if so it seemed fit to him for the good of the Plantation, and Pocahuntas herself acquainted her brethren therewith.” Governor Dale approved this, and consequently was willing to retire without other conditions. “The bruite of this pretended marriage [Hamor continues] came soon to Powhatan's knowledge, a thing acceptable to him, as appeared by his sudden consent thereunto, who some ten daies after sent an old uncle of hirs, named Opachisco, to give her as his deputy in the church, and two of his sonnes to see the mariage solemnized which was accordingly done about the fifth of April 1614, and ever since we have had friendly commerce and trade, not only with Powhatan himself, but also with his subjects round about us; so as now I see no reason why the collonie should not thrive a pace.”

This marriage was justly celebrated as the means and beginning of a firm peace which long continued, so that Pocahontas was again entitled to the grateful remembrance of the Virginia settlers. Already, in 1612, a plan had been mooted in Virginia of marrying the English with the natives, and of obtaining the recognition of Powhatan and those allied to him as members of a fifth kingdom, with certain privileges. Cunega, the Spanish ambassador at London, on September 22, 1612, writes: “Although some suppose the plantation to decrease, he is credibly informed that there is a determination to marry some of the people that go over to Virginia; forty or fifty are already so married, and English women intermingle and are received kindly by the natives. A zealous minister hath been wounded for reprehending it.”

Mr. John Rolfe was a man of industry, and apparently devoted to the welfare of the colony. He probably brought with him in 1610 his wife, who gave birth to his daughter Bermuda, born on the Somers Islands at the time of the shipwreck. We find no notice of her death. Hamor gives him the distinction of being the first in the colony to try, in 1612, the planting and raising of tobacco. “No man [he adds] hath labored to his power, by good example there and worthy encouragement into England by his letters, than he hath done, witness his marriage with Powhatan's daughter, one of rude education, manners barbarous and cursed generation, meerely for the good and honor of the plantation: and least any man should conceive that some sinister respects allured him hereunto, I have made bold, contrary to his knowledge, in the end of my treatise to insert the true coppie of his letter written to Sir Thomas Dale.”

The letter is a long, labored, and curious document, and comes nearer to a theological treatise than any love-letter we have on record. It reeks with unction. Why Rolfe did not speak to Dale, whom he saw every day, instead of inflicting upon him this painful document, in which the flutterings of a too susceptible widower's heart are hidden under a great resolve of self-sacrifice, is not plain.

The letter protests in a tedious preamble that the writer is moved entirely by the Spirit of God, and continues:

“Let therefore this my well advised protestation, which here I make between God and my own conscience, be a sufficient witness, at the dreadful day of judgment (when the secrets of all men's hearts shall be opened) to condemne me herein, if my chiefest interest and purpose be not to strive with all my power of body and mind, in the undertaking of so weighty a matter, no way led (so far forth as man's weakness may permit) with the unbridled desire of carnall affection; but for the good of this plantation, for the honour of our countrie, for the glory of God, for my owne salvation, and for the converting to the true knowledge of God and Jesus Christ, an unbelieving creature, namely Pokahuntas. To whom my heartie and best thoughts are, and have a long time bin so entangled, and inthralled in so intricate a laborinth, that I was even awearied to unwinde myself thereout.”

Master Rolfe goes on to describe the mighty war in his meditations on this subject, in which he had set before his eyes the frailty of mankind and his proneness to evil and wicked thoughts. He is aware of God's displeasure against the sons of Levi and Israel for marrying strange wives, and this has caused him to look about warily and with good circumspection “into the grounds and principall agitations which should thus provoke me to be in love with one, whose education hath bin rude, her manners barbarous, her generation accursed, and so discrepant in all nurtriture from myselfe, that oftentimes with feare and trembling, I have ended my private controversie with this: surely these are wicked instigations, fetched by him who seeketh and delighteth in man's distruction; and so with fervent prayers to be ever preserved from such diabolical assaults (as I looke those to be) I have taken some rest.”

The good man was desperately in love and wanted to marry the Indian, and consequently he got no peace; and still being tormented with her image, whether she was absent or present, he set out to produce an ingenious reason (to show the world) for marrying her. He continues:

“Thus when I thought I had obtained my peace and quietnesse, beholde another, but more gracious tentation hath made breaches into my holiest and strongest meditations; with which I have been put to a new triall, in a straighter manner than the former; for besides the weary passions and sufferings which I have dailey, hourely, yea and in my sleepe indured, even awaking me to astonishment, taxing me with remissnesse, and carelessnesse, refusing and neglecting to perform the duteie of a good Christian, pulling me by the eare, and crying: Why dost thou not indeavor to make her a Christian? And these have happened to my greater wonder, even when she hath been furthest seperated from me, which in common reason (were it not an undoubted work of God) might breede forgetfulnesse of a far more worthie creature.”

He accurately describes the symptoms and appears to understand the remedy, but he is after a large-sized motive:

“Besides, I say the holy Spirit of God hath often demanded of me, why I was created? If not for transitory pleasures and worldly vanities, but to labour in the Lord's vineyard, there to sow and plant, to nourish and increase the fruites thereof, daily adding with the good husband in the gospell, somewhat to the tallent, that in the ends the fruites may be reaped, to the comfort of the labourer in this life, and his salvation in the world to come.... Likewise, adding hereunto her great appearance of love to me, her desire to be taught and instructed in the knowledge of God, her capablenesse of understanding, her aptness and willingness to receive anie good impression, and also the spirituall, besides her owne incitements stirring me up hereunto.”

The “incitements” gave him courage, so that he exclaims: “Shall I be of so untoward a disposition, as to refuse to lead the blind into the right way? Shall I be so unnatural, as not to give bread to the hungrie, or uncharitable, as not to cover the naked?”

It wasn't to be thought of, such wickedness; and so Master Rolfe screwed up his courage to marry the glorious Princess, from whom thousands of people were afterwards so anxious to be descended. But he made the sacrifice for the glory of the country, the benefit of the plantation, and the conversion of the unregenerate, and other and lower motive he vigorously repels: “Now, if the vulgar sort, who square all men's actions by the base rule of their own filthinesse, shall tax or taunt mee in this my godly labour: let them know it is not hungry appetite, to gorge myselfe with incontinency; sure (if I would and were so sensually inclined) I might satisfy such desire, though not without a seared conscience, yet with Christians more pleasing to the eie, and less fearefull in the offense unlawfully committed. Nor am I in so desperate an estate, that I regard not what becometh of me; nor am I out of hope but one day to see my country, nor so void of friends, nor mean in birth, but there to obtain a mach to my great con'tent.... But shall it please God thus to dispose of me (which I earnestly desire to fulfill my ends before set down) I will heartily accept of it as a godly taxe appointed me, and I will never cease (God assisting me) untill I have accomplished, and brought to perfection so holy a worke, in which I will daily pray God to bless me, to mine and her eternal happiness.”

It is to be hoped that if sanctimonious John wrote any love-letters to Amonata they had less cant in them than this. But it was pleasing to Sir Thomas Dale, who was a man to appreciate the high motives of Mr. Rolfe. In a letter which he despatched from Jamestown, June 18, 1614, to a reverend friend in London, he describes the expedition when Pocahontas was carried up the river, and adds the information that when she went on shore, “she would not talk to any of them, scarcely to them of the best sort, and to them only, that if her father had loved her, he would not value her less than old swords, pieces, or axes; wherefore she would still dwell with the Englishmen who loved her.”

“Powhatan's daughter [the letter continues] I caused to be carefully instructed in Christian Religion, who after she had made some good progress therein, renounced publically her countrey idolatry, openly confessed her Christian faith, was, as she desired, baptized, and is since married to an English Gentleman of good understanding (as by his letter unto me, containing the reasons for his marriage of her you may perceive), an other knot to bind this peace the stronger. Her father and friends gave approbation to it, and her uncle gave her to him in the church; she lives civilly and lovingly with him, and I trust will increase in goodness, as the knowledge of God increaseth in her. She will goe into England with me, and were it but the gayning of this one soule, I will think my time, toile, and present stay well spent.”

Hamor also appends to his narration a short letter, of the same date with the above, from the minister Alexander Whittaker, the genuineness of which is questioned. In speaking of the good deeds of Sir Thomas Dale it says: “But that which is best, one Pocahuntas or Matoa, the daughter of Powhatan, is married to an honest and discreet English Gentleman—Master Rolfe, and that after she had openly renounced her countrey Idolatry, and confessed the faith of Jesus Christ, and was baptized, which thing Sir Thomas Dale had laboured a long time to ground her in.” If, as this proclaims, she was married after her conversion, then Rolfe's tender conscience must have given him another twist for wedding her, when the reason for marrying her (her conversion) had ceased with her baptism. His marriage, according to this, was a pure work of supererogation. It took place about the 5th of April, 1614. It is not known who performed the ceremony.

How Pocahontas passed her time in Jamestown during the period of her detention, we are not told. Conjectures are made that she was an inmate of the house of Sir Thomas Dale, or of that of the Rev. Mr. Whittaker, both of whom labored zealously to enlighten her mind on religious subjects. She must also have been learning English and civilized ways, for it is sure that she spoke our language very well when she went to London. Mr. John Rolfe was also laboring for her conversion, and we may suppose that with all these ministrations, mingled with her love of Mr. Rolfe, which that ingenious widower had discovered, and her desire to convert him into a husband, she was not an unwilling captive. Whatever may have been her barbarous instincts, we have the testimony of Governor Dale that she lived “civilly and lovingly” with her husband.

Sir Thomas Dale was on the whole the most efficient and discreet Governor the colony had had. One element of his success was no doubt the change in the charter of 1609. By the first charter everything had been held in common by the company, and there had been no division of property or allotment of land among the colonists. Under the new regime land was held in severalty, and the spur of individual interest began at once to improve the condition of the settlement. The character of the colonists was also gradually improving. They had not been of a sort to fulfill the earnest desire of the London promoter's to spread vital piety in the New World. A zealous defense of Virginia and Maryland, against “scandalous imputation,” entitled “Leah and Rachel; or, The Two Fruitful Sisters,” by Mr. John Hammond, London, 1656, considers the charges that Virginia “is an unhealthy place, a nest of rogues, abandoned women, dissolut and rookery persons; a place of intolerable labour, bad usage and hard diet”; and admits that “at the first settling, and for many years after, it deserved most of these aspersions, nor were they then aspersions but truths.... There were jails supplied, youth seduced, infamous women drilled in, the provision all brought out of England, and that embezzled by the Trustees.”

Governor Dale was a soldier; entering the army in the Netherlands as a private he had risen to high position, and received knighthood in 1606. Shortly after he was with Sir Thomas Gates in South Holland. The States General in 1611 granted him three years' term of absence in Virginia. Upon his arrival he began to put in force that system of industry and frugality he had observed in Holland. He had all the imperiousness of a soldier, and in an altercation with Captain Newport, occasioned by some injurious remarks the latter made about Sir Thomas Smith, the treasurer, he pulled his beard and threatened to hang him. Active operations for settling new plantations were at once begun, and Dale wrote to Cecil, the Earl of Salisbury, for 2,000 good colonists to be sent out, for the three hundred that came were “so profane, so riotous, so full of mutiny, that not many are Christians but in name, their bodies so diseased and crazed that not sixty of them may be employed.” He served afterwards with credit in Holland, was made commander of the East Indian fleet in 1618, had a naval engagement with the Dutch near Bantam in 1619, and died in 1620 from the effects of the climate. He was twice married, and his second wife, Lady Fanny, the cousin of his first wife, survived him and received a patent for a Virginia plantation.

Governor Dale kept steadily in view the conversion of the Indians to Christianity, and the success of John Rolfe with Matoaka inspired him with a desire to convert another daughter of Powhatan, of whose exquisite perfections he had heard. He therefore despatched Ralph Hamor, with the English boy, Thomas Savage, as interpreter, on a mission to the court of Powhatan, “upon a message unto him, which was to deale with him, if by any means I might procure a daughter of his, who (Pocahuntas being already in our possession) is generally reported to be his delight and darling, and surely he esteemed her as his owne Soule, for surer pledge of peace.” This visit Hamor relates with great naivete.

At his town of Matchcot, near the head of York River, Powhatan himself received his visitors when they landed, with great cordiality, expressing much pleasure at seeing again the boy who had been presented to him by Captain Newport, and whom he had not seen since he gave him leave to go and see his friends at Jamestown four years before; he also inquired anxiously after Namontack, whom he had sent to King James's land to see him and his country and report thereon, and then led the way to his house, where he sat down on his bedstead side. “On each hand of him was placed a comely and personable young woman, which they called his Queenes, the howse within round about beset with them, the outside guarded with a hundred bowmen.”

The first thing offered was a pipe of tobacco, which Powhatan “first drank,” and then passed to Hamor, who “drank” what he pleased and then returned it. The Emperor then inquired how his brother Sir Thomas Dale fared, “and after that of his daughter's welfare, her marriage, his unknown son, and how they liked, lived and loved together.” Hamor replied “that his brother was very well, and his daughter so well content that she would not change her life to return and live with him, whereat he laughed heartily, and said he was very glad of it.”

Powhatan then desired to know the cause of his unexpected coming, and Mr. Hamor said his message was private, to be delivered to him without the presence of any except one of his councilors, and one of the guides, who already knew it.

Therefore the house was cleared of all except the two Queens, who may never sequester themselves, and Mr. Hamor began his palaver. First there was a message of love and inviolable peace, the production of presents of coffee, beads, combs, fish-hooks, and knives, and the promise of a grindstone when it pleased the Emperor to send for it. Hamor then proceeded:

“The bruite of the exquesite perfection of your youngest daughter, being famous through all your territories, hath come to the hearing of your brother, Sir Thomas Dale, who for this purpose hath addressed me hither, to intreate you by that brotherly friendship you make profession of, to permit her (with me) to returne unto him, partly for the desire which himselfe hath, and partly for the desire her sister hath to see her of whom, if fame hath not been prodigall, as like enough it hath not, your brother (by your favour) would gladly make his nearest companion, wife and bed fellow [many times he would have interrupted my speech, which I entreated him to heare out, and then if he pleased to returne me answer], and the reason hereof is, because being now friendly and firmly united together, and made one people [as he supposeth and believes] in the bond of love, he would make a natural union between us, principally because himself hath taken resolution to dwel in your country so long as he liveth, and would not only therefore have the firmest assurance hee may, of perpetuall friendship from you, but also hereby binde himselfe thereunto.”

Powhatan replied with dignity that he gladly accepted the salute of love and peace, which he and his subjects would exactly maintain. But as to the other matter he said: “My daughter, whom my brother desireth, I sold within these three days to be wife to a great Weroance for two bushels of Roanoke [a small kind of beads made of oyster shells], and it is true she is already gone with him, three days' journey from me.”

Hamor persisted that this marriage need not stand in the way; “that if he pleased herein to gratify his Brother he might, restoring the Roanoke without the imputation of injustice, take home his daughter again, the rather because she was not full twelve years old, and therefore not marriageable; assuring him besides the bond of peace, so much the firmer, he should have treble the price of his daughter in beads, copper, hatchets, and many other things more useful for him.”

The reply of the noble old savage to this infamous demand ought to have brought a blush to the cheeks of those who made it. He said he loved his daughter as dearly as his life; he had many children, but he delighted in none so much as in her; he could not live if he did not see her often, as he would not if she were living with the whites, and he was determined not to put himself in their hands. He desired no other assurance of friendship than his brother had given him, who had already one of his daughters as a pledge, which was sufficient while she lived; “when she dieth he shall have another child of mine.” And then he broke forth in pathetic eloquence: “I hold it not a brotherly part of your King, to desire to bereave me of two of my children at once; further give him to understand, that if he had no pledge at all, he should not need to distrust any injury from me, or any under my subjection; there have been too many of his and my men killed, and by my occasion there shall never be more; I which have power to perform it have said it; no not though I should have just occasion offered, for I am now old and would gladly end my days in peace; so as if the English offer me any injury, my country is large enough, I will remove myself farther from you.”

The old man hospitably entertained his guests for a day or two, loaded them with presents, among which were two dressed buckskins, white as snow, for his son and daughter, and, requesting some articles sent him in return, bade them farewell with this message to Governor Dale: “I hope this will give him good satisfaction, if it do not I will go three days' journey farther from him, and never see Englishmen more.” It speaks well for the temperate habits of this savage that after he had feasted his guests, “he caused to be fetched a great glass of sack, some three quarts or better, which Captain Newport had given him six or seven years since, carefully preserved by him, not much above a pint in all this time spent, and gave each of us in a great oyster shell some three spoonfuls.”

We trust that Sir Thomas Dale gave a faithful account of all this to his wife in England.

Sir Thomas Gates left Virginia in the spring of 1614 and never returned. After his departure scarcity and severity developed a mutiny, and six of the settlers were executed. Rolfe was planting tobacco (he has the credit of being the first white planter of it), and his wife was getting an inside view of Christian civilization.

In 1616 Sir Thomas Dale returned to England with his company and John Rolfe and Pocahontas, and several other Indians. They reached Plymouth early in June, and on the 20th Lord Carew made this note: “Sir Thomas Dale returned from Virginia; he hath brought divers men and women of thatt countrye to be educated here, and one Rolfe who married a daughter of Pohetan (the barbarous prince) called Pocahuntas, hath brought his wife with him into England.” On the 22d Sir John Chamberlain wrote to Sir Dudley Carlton that there were “ten or twelve, old and young, of that country.”

The Indian girls who came with Pocahontas appear to have been a great care to the London company. In May, 1620, is a record that the company had to pay for physic and cordials for one of them who had been living as a servant in Cheapside, and was very weak of a consumption. The same year two other of the maids were shipped off to the Bermudas, after being long a charge to the company, in the hope that they might there get husbands, “that after they were converted and had children, they might be sent to their country and kindred to civilize them.” One of them was there married. The attempt to educate them in England was not very successful, and a proposal to bring over Indian boys obtained this comment from Sir Edwin Sandys:

“Now to send for them into England, and to have them educated here, he found upon experience of those brought by Sir Thomas Dale, might be far from the Christian work intended.” One Nanamack, a lad brought over by Lord Delaware, lived some years in houses where “he heard not much of religion but sins, had many times examples of drinking, swearing and like evils, ran as he was a mere Pagan,” till he fell in with a devout family and changed his life, but died before he was baptized. Accompanying Pocahontas was a councilor of Powhatan, one Tomocomo, the husband of one of her sisters, of whom Purchas says in his “Pilgrimes”: “With this savage I have often conversed with my good friend Master Doctor Goldstone where he was a frequent geust, and where I have seen him sing and dance his diabolical measures, and heard him discourse of his country and religion.... Master Rolfe lent me a discourse which I have in my Pilgrimage delivered. And his wife did not only accustom herself to civility, but still carried herself as the daughter of a king, and was accordingly respected, not only by the Company which allowed provision for herself and her son, but of divers particular persons of honor, in their hopeful zeal by her to advance Christianity. I was present when my honorable and reverend patron, the Lord Bishop of London, Doctor King, entertained her with festival state and pomp beyond what I had seen in his great hospitality offered to other ladies. At her return towards Virginia she came at Gravesend to her end and grave, having given great demonstration of her Christian sincerity, as the first fruits of Virginia conversion, leaving here a goodly memory, and the hopes of her resurrection, her soul aspiring to see and enjoy permanently in heaven what here she had joyed to hear and believe of her blessed Saviour. Not such was Tomocomo, but a blasphemer of what he knew not and preferring his God to ours because he taught them (by his own so appearing) to wear their Devil-lock at the left ear; he acquainted me with the manner of that his appearance, and believed that their Okee or Devil had taught them their husbandry.”

Upon news of her arrival, Captain Smith, either to increase his own importance or because Pocahontas was neglected, addressed a letter or “little booke” to Queen Anne, the consort of King James. This letter is found in Smith's “General Historie” ( 1624), where it is introduced as having been sent to Queen Anne in 1616. Probably he sent her such a letter. We find no mention of its receipt or of any acknowledgment of it. Whether the “abstract” in the “General Historie” is exactly like the original we have no means of knowing. We have no more confidence in Smith's memory than we have in his dates. The letter is as follows:

“To the most high and vertuous Princesse Queene Anne of Great Brittaine.

“Most ADMIRED QUEENE.

“The love I beare my God, my King and Countrie hath so oft emboldened me in the worst of extreme dangers, that now honestie doth constraine mee presume thus farre beyond my selfe, to present your Majestie this short discourse: if ingratitude be a deadly poyson to all honest vertues, I must be guiltie of that crime if I should omit any meanes to bee thankful. So it is.

“That some ten yeeres agoe being in Virginia, and taken prisoner by the power of Powhaten, their chiefe King, I received from this great Salvage exceeding great courtesie, especially from his sonne Nantaquaus, the most manliest, comeliest, boldest spirit, I ever saw in a Salvage and his sister Pocahontas, the Kings most deare and well-beloved daughter, being but a childe of twelve or thirteen yeeres of age, whose compassionate pitifull heart, of desperate estate, gave me much cause to respect her: I being the first Christian this proud King and his grim attendants ever saw, and thus enthralled in their barbarous power, I cannot say I felt the least occasion of want that was in the power of those my mortall foes to prevent notwithstanding al their threats. After some six weeks fatting amongst those Salvage Courtiers, at the minute of my execution, she hazarded the beating out of her owne braines to save mine, and not onely that, but so prevailed with her father, that I was safely conducted to Jamestowne, where I found about eight and thirty miserable poore and sicke creatures, to keepe possession of all those large territories of Virginia, such was the weaknesse of this poore Commonwealth, as had the Salvages not fed us, we directly had starved.

“And this reliefe, most gracious Queene, was commonly brought us by this Lady Pocahontas, notwithstanding all these passages when inconstant Fortune turned our Peace to warre, this tender Virgin would still not spare to dare to visit us, and by her our jarres have been oft appeased, and our wants still supplyed; were it the policie of her father thus to imploy her, or the ordinance of God thus to make her his instrument, or her extraordinarie affection to our Nation, I know not: but of this I am sure: when her father with the utmost of his policie and power, sought to surprize mee, having but eighteene with mee, the dark night could not affright her from comming through the irksome woods, and with watered eies gave me intilligence, with her best advice to escape his furie: which had hee known hee had surely slaine her. Jamestowne with her wild traine she as freely frequented, as her father's habitation: and during the time of two or three yeares, she next under God, was still the instrument to preserve this Colonie from death, famine and utter confusion, which if in those times had once beene dissolved, Virginia might have laine as it was at our first arrivall to this day. Since then, this buisinesse having been turned and varied by many accidents from that I left it at: it is most certaine, after a long and troublesome warre after my departure, betwixt her father and our Colonie, all which time shee was not heard of, about two yeeres longer, the Colonie by that meanes was releived, peace concluded, and at last rejecting her barbarous condition, was maried to an English Gentleman, with whom at this present she is in England; the first Christian ever of that Nation, the first Virginian ever spake English, or had a childe in mariage by an Englishman, a matter surely, if my meaning bee truly considered and well understood, worthy a Princes understanding.

“Thus most gracious Lady, I have related to your Majestic, what at your best leasure our approved Histories will account you at large, and done in the time of your Majesties life, and however this might bee presented you from a more worthy pen, it cannot from a more honest heart, as yet I never begged anything of the State, or any, and it is my want of abilitie and her exceeding desert, your birth, meanes, and authoritie, her birth, vertue, want and simplicitie, doth make mee thus bold, humbly to beseech your Majestic: to take this knowledge of her though it be from one so unworthy to be the reporter, as myselfe, her husband's estate not being able to make her fit to attend your Majestic: the most and least I can doe, is to tell you this, because none so oft hath tried it as myselfe: and the rather being of so great a spirit, however her station: if she should not be well received, seeing this Kingdome may rightly have a Kingdome by her meanes: her present love to us and Christianitie, might turne to such scorne and furie, as to divert all this good to the worst of evill, when finding so great a Queene should doe her some honour more than she can imagine, for being so kinde to your servants and subjects, would so ravish her with content, as endeare her dearest bloud to effect that, your Majestic and all the Kings honest subjects most earnestly desire: and so I humbly kisse your gracious hands.”

The passage in this letter, “She hazarded the beating out of her owne braines to save mine,” is inconsistent with the preceding portion of the paragraph which speaks of “the exceeding great courtesie” of Powhatan; and Smith was quite capable of inserting it afterwards when he made up his “General Historie.”

Smith represents himself at this time—the last half of 1616 and the first three months of 1617—as preparing to attempt a third voyage to New England (which he did not make), and too busy to do Pocahontas the service she desired. She was staying at Branford, either from neglect of the company or because the London smoke disagreed with her, and there Smith went to see her. His account of his intercourse with her, the only one we have, must be given for what it is worth. According to this she had supposed Smith dead, and took umbrage at his neglect of her. He writes:

“After a modest salutation, without any word, she turned about, obscured her face, as not seeming well contented; and in that humour, her husband with divers others, we all left her two or three hours repenting myself to have writ she could speak English. But not long after she began to talke, remembering me well what courtesies she had done: saying, 'You did promise Powhatan what was yours should be his, and he the like to you; you called him father, being in his land a stranger, and by the same reason so must I do you:' which though I would have excused, I durst not allow of that title, because she was a king's daughter. With a well set countenance she said: 'Were you not afraid to come into my father's country and cause fear in him and all his people (but me), and fear you have I should call you father; I tell you then I will, and you shall call me childe, and so I will be forever and ever, your contrieman. They did tell me alwaies you were dead, and I knew no other till I came to Plymouth, yet Powhatan did command Uttamatomakkin to seek you, and know the truth, because your countriemen will lie much.”'

This savage was the Tomocomo spoken of above, who had been sent by Powhatan to take a census of the people of England, and report what they and their state were. At Plymouth he got a long stick and began to make notches in it for the people he saw. But he was quickly weary of that task. He told Smith that Powhatan bade him seek him out, and get him to show him his God, and the King, Queen, and Prince, of whom Smith had told so much. Smith put him off about showing his God, but said he had heard that he had seen the King. This the Indian denied, James probably not coming up to his idea of a king, till by circumstances he was convinced he had seen him. Then he replied very sadly: “You gave Powhatan a white dog, which Powhatan fed as himself, but your king gave me nothing, and I am better than your white dog.”

Smith adds that he took several courtiers to see Pocahontas, and “they did think God had a great hand in her conversion, and they have seen many English ladies worse favoured, proportioned, and behavioured;” and he heard that it had pleased the King and Queen greatly to esteem her, as also Lord and Lady Delaware, and other persons of good quality, both at the masques and otherwise.

Much has been said about the reception of Pocahontas in London, but the contemporary notices of her are scant. The Indians were objects of curiosity for a time in London, as odd Americans have often been since, and the rank of Pocahontas procured her special attention. She was presented at court. She was entertained by Dr. King, Bishop of London. At the playing of Ben Jonson's “Christmas his Mask” at court, January 6, 1616-17, Pocahontas and Tomocomo were both present, and Chamberlain writes to Carleton: “The Virginian woman Pocahuntas with her father counsellor have been with the King and graciously used, and both she and her assistant were pleased at the Masque. She is upon her return though sore against her will, if the wind would about to send her away.”

Mr. Neill says that “after the first weeks of her residence in England she does not appear to be spoken of as the wife of Rolfe by the letter writers,” and the Rev. Peter Fontaine says that “when they heard that Rolfe had married Pocahontas, it was deliberated in council whether he had not committed high treason by so doing, that is marrying an Indian princesse.”

It was like James to think so. His interest in the colony was never the most intelligent, and apt to be in things trivial. Lord Southampton (Dec. 15, 1609) writes to Lord Salisbury that he had told the King of the Virginia squirrels brought into England, which are said to fly. The King very earnestly asked if none were provided for him, and said he was sure Salisbury would get him one. Would not have troubled him, “but that you know so well how he is affected to these toys.”

There has been recently found in the British Museum a print of a portrait of Pocahontas, with a legend round it in Latin, which is translated: “Matoaka, alias Rebecka, Daughter of Prince Powhatan, Emperor of Virginia; converted to Christianity, married Mr. Rolff; died on shipboard at Gravesend 1617.” This is doubtless the portrait engraved by Simon De Passe in 1616, and now inserted in the extant copies of the London edition of the “General Historie,” 1624. It is not probable that the portrait was originally published with the “General Historie.” The portrait inserted in the edition of 1624 has this inscription:

Round the portrait:

“Matoaka als Rebecca Filia Potentiss Princ: Pohatani Imp: Virginim.”

In the oval, under the portrait:

“Aetatis suae 21 A.

1616”

“Matoaks als Rebecka daughter to the mighty Prince Powhatan Emprour of Attanoughkomouck als virginia converted and baptized in the Christian faith, and wife to the worth Mr. job Rolff. i: Pass: sculp. Compton Holland excud.”

Camden in his “History of Gravesend” says that everybody paid this young lady all imaginable respect, and it was believed she would have sufficiently acknowledged those favors, had she lived to return to her own country, by bringing the Indians to a kinder disposition toward the English; and that she died, “giving testimony all the time she lay sick, of her being a very good Christian.”

The Lady Rebecka, as she was called in London, died on shipboard at Gravesend after a brief illness, said to be of only three days, probably on the 21st of March, 1617. I have seen somewhere a statement, which I cannot confirm, that her disease was smallpox. St. George's Church, where she was buried, was destroyed by fire in 1727. The register of that church has this record:

“1616, May 21 Rebecca Wrothe

Wyff of Thomas Wroth gent

A Virginia lady borne, here was buried

in ye chaunncle.”

Yet there is no doubt, according to a record in the Calendar of State Papers, dated “1617, 29 March, London,” that her death occurred March 21, 1617.

John Rolfe was made Secretary of Virginia when Captain Argall became Governor, and seems to have been associated in the schemes of that unscrupulous person and to have forfeited the good opinion of the company. August 23, 1618, the company wrote to Argall: “We cannot imagine why you should give us warning that Opechankano and the natives have given the country to Mr. Rolfe's child, and that they reserve it from all others till he comes of years except as we suppose as some do here report it be a device of your own, to some special purpose for yourself.” It appears also by the minutes of the company in 1621 that Lady Delaware had trouble to recover goods of hers left in Rolfe's hands in Virginia, and desired a commission directed to Sir Thomas Wyatt and Mr. George Sandys to examine what goods of the late “Lord Deleware had come into Rolfe's possession and get satisfaction of him.” This George Sandys is the famous traveler who made a journey through the Turkish Empire in 1610, and who wrote, while living in Virginia, the first book written in the New World, the completion of his translation of Ovid's “Metamorphosis.”

John Rolfe died in Virginia in 1622, leaving a wife and children. This is supposed to be his third wife, though there is no note of his marriage to her nor of the death of his first. October 7, 1622, his brother Henry Rolfe petitioned that the estate of John should be converted to the support of his relict wife and children and to his own indemnity for having brought up John's child by Powhatan's daughter.

This child, named Thomas Rolfe, was given after the death of Pocahontas to the keeping of Sir Lewis Stukely of Plymouth, who fell into evil practices, and the boy was transferred to the guardianship of his uncle Henry Rolfe, and educated in London. When he was grown up he returned to Virginia, and was probably there married. There is on record his application to the Virginia authorities in 1641 for leave to go into the Indian country and visit Cleopatra, his mother's sister. He left an only daughter who was married, says Stith (1753), “to Col. John Bolling; by whom she left an only son, the late Major John Bolling, who was father to the present Col. John Bolling, and several daughters, married to Col. Richard Randolph, Col. John Fleming, Dr. William Gay, Mr. Thomas Eldridge, and Mr. James Murray.” Campbell in his “History of Virginia” says that the first Randolph that came to the James River was an esteemed and industrious mechanic, and that one of his sons, Richard, grandfather of the celebrated John Randolph, married Jane Bolling, the great granddaughter of Pocahontas.

In 1618 died the great Powhatan, full of years and satiated with fighting and the savage delights of life. He had many names and titles; his own people sometimes called him Ottaniack, sometimes Mamauatonick, and usually in his presence Wahunsenasawk. He ruled, by inheritance and conquest, with many chiefs under him, over a large territory with not defined borders, lying on the James, the York, the Rappahannock, the Potomac, and the Pawtuxet Rivers. He had several seats, at which he alternately lived with his many wives and guard of bowmen, the chief of which at the arrival of the English was Werowomocomo, on the Pamunkey (York) River. His state has been sufficiently described. He is said to have had a hundred wives, and generally a dozen—the youngest—personally attending him. When he had a mind to add to his harem he seems to have had the ancient oriental custom of sending into all his dominions for the fairest maidens to be brought from whom to select. And he gave the wives of whom he was tired to his favorites.

Strachey makes a striking description of him as he appeared about 1610: “He is a goodly old man not yet shrincking, though well beaten with cold and stormeye winters, in which he hath been patient of many necessityes and attempts of his fortune to make his name and famely great. He is supposed to be little lesse than eighty yeares old, I dare not saye how much more; others saye he is of a tall stature and cleane lymbes, of a sad aspect, rownd fatt visaged, with graie haires, but plaine and thin, hanging upon his broad showlders; some few haires upon his chin, and so on his upper lippe: he hath been a strong and able salvadge, synowye, vigilant, ambitious, subtile to enlarge his dominions:... cruell he hath been, and quarellous as well with his own wcrowanccs for trifles, and that to strike a terrour and awe into them of his power and condicion, as also with his neighbors in his younger days, though now delighted in security and pleasure, and therefore stands upon reasonable conditions of peace with all the great and absolute werowances about him, and is likewise more quietly settled amongst his own.”

It was at this advanced age that he had the twelve favorite young wives whom Strachey names. All his people obeyed him with fear and adoration, presenting anything he ordered at his feet, and trembling if he frowned. His punishments were cruel; offenders were beaten to death before him, or tied to trees and dismembered joint by joint, or broiled to death on burning coals. Strachey wondered how such a barbarous prince should put on such ostentation of majesty, yet he accounted for it as belonging to the necessary divinity that doth hedge in a king: “Such is (I believe) the impression of the divine nature, and however these (as other heathens forsaken by the true light) have not that porcion of the knowing blessed Christian spiritt, yet I am perswaded there is an infused kind of divinities and extraordinary (appointed that it shall be so by the King of kings) to such as are his ymedyate instruments on earth.”

Here is perhaps as good a place as any to say a word or two about the appearance and habits of Powhatan's subjects, as they were observed by Strachey and Smith. A sort of religion they had, with priests or conjurors, and houses set apart as temples, wherein images were kept and conjurations performed, but the ceremonies seem not worship, but propitiations against evil, and there seems to have been no conception of an overruling power or of an immortal life. Smith describes a ceremony of sacrifice of children to their deity; but this is doubtful, although Parson Whittaker, who calls the Indians “naked slaves of the devil,” also says they sacrificed sometimes themselves and sometimes their own children. An image of their god which he sent to England “was painted upon one side of a toadstool, much like unto a deformed monster.” And he adds: “Their priests, whom they call Quockosoughs, are no other but such as our English witches are.” This notion I believe also pertained among the New England colonists. There was a belief that the Indian conjurors had some power over the elements, but not a well-regulated power, and in time the Indians came to a belief in the better effect of the invocations of the whites. In “Winslow's Relation,” quoted by Alexander Young in his “Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers,” under date of July, 1623, we read that on account of a great drought a fast day was appointed. When the assembly met the sky was clear. The exercise lasted eight or nine hours. Before they broke up, owing to prayers the weather was overcast. Next day began a long gentle rain. This the Indians seeing, admired the goodness of our God: “showing the difference between their conjuration and our invocation in the name of God for rain; theirs being mixed with such storms and tempests, as sometimes, instead of doing them good, it layeth the corn flat on the ground; but ours in so gentle and seasonable a manner, as they never observed the like.”

It was a common opinion of the early settlers in Virginia, as it was of those in New England, that the Indians were born white, but that they got a brown or tawny color by the use of red ointments, made of earth and the juice of roots, with which they besmear themselves either according to the custom of the country or as a defense against the stinging of mosquitoes. The women are of the same hue as the men, says Strachey; “howbeit, it is supposed neither of them naturally borne so discolored; for Captain Smith (lyving sometymes amongst them) affirmeth how they are from the womb indifferent white, but as the men, so doe the women,” “dye and disguise themselves into this tawny cowler, esteeming it the best beauty to be nearest such a kind of murrey as a sodden quince is of,” as the Greek women colored their faces and the ancient Britain women dyed themselves with red; “howbeit [Strachey slyly adds] he or she that hath obtained the perfected art in the tempering of this collour with any better kind of earth, yearb or root preserves it not yet so secrett and precious unto herself as doe our great ladyes their oyle of talchum, or other painting white and red, but they frindly communicate the secret and teach it one another.”

Thomas Lechford in his “Plain Dealing; or Newes from New England,” London, 1642, says: “They are of complexion swarthy and tawny; their children are borne white, but they bedawbe them with oyle and colors presently.”

The men are described as tall, straight, and of comely proportions; no beards; hair black, coarse, and thick; noses broad, flat, and full at the end; with big lips and wide mouths', yet nothing so unsightly as the Moors; and the women as having “handsome limbs, slender arms, pretty hands, and when they sing they have a pleasant tange in their voices. The men shaved their hair on the right side, the women acting as barbers, and left the hair full length on the left side, with a lock an ell long.” A Puritan divine—“New England's Plantation, 1630”—says of the Indians about him, “their hair is generally black, and cut before like our gentlewomen, and one lock longer than the rest, much like to our gentlemen, which fashion I think came from hence into England.”

Their love of ornaments is sufficiently illustrated by an extract from Strachey, which is in substance what Smith writes:

“Their eares they boare with wyde holes, commonly two or three, and in the same they doe hang chaines of stayned pearle braceletts, of white bone or shreeds of copper, beaten thinne and bright, and wounde up hollowe, and with a grate pride, certaine fowles' legges, eagles, hawkes, turkeys, etc., with beasts clawes, bears, arrahacounes, squirrells, etc. The clawes thrust through they let hang upon the cheeke to the full view, and some of their men there be who will weare in these holes a small greene and yellow-couloured live snake, neere half a yard in length, which crawling and lapping himself about his neck oftentymes familiarly, he suffreeth to kisse his lippes. Others weare a dead ratt tyed by the tayle, and such like conundrums.”

This is the earliest use I find of our word “conundrum,” and the sense it bears here may aid in discovering its origin.

Powhatan is a very large figure in early Virginia history, and deserves his prominence. He was an able and crafty savage, and made a good fight against the encroachments of the whites, but he was no match for the crafty Smith, nor the double-dealing of the Christians. There is something pathetic about the close of his life, his sorrow for the death of his daughter in a strange land, when he saw his territories overrun by the invaders, from whom he only asked peace, and the poor privilege of moving further away from them into the wilderness if they denied him peace.

In the midst of this savagery Pocahontas blooms like a sweet, wild rose. She was, like the Douglas, “tender and true.” Wanting apparently the cruel nature of her race generally, her heroic qualities were all of the heart. No one of all the contemporary writers has anything but gentle words for her. Barbarous and untaught she was like her comrades, but of a gentle nature. Stripped of all the fictions which Captain Smith has woven into her story, and all the romantic suggestions which later writers have indulged in, she appears, in the light of the few facts that industry is able to gather concerning her, as a pleasing and unrestrained Indian girl, probably not different from her savage sisters in her habits, but bright and gentle; struck with admiration at the appearance of the white men, and easily moved to pity them, and so inclined to a growing and lasting friendship for them; tractable and apt to learn refinements; accepting the new religion through love for those who taught it, and finally becoming in her maturity a well-balanced, sensible, dignified Christian woman.