- Home

- History

-

Controversies

- Controversies

- Is John Smith's account of his rescue by Pocahontas true?

- Did John Smith misunderstand a Powhatan 'adoption ceremony'?

- What was the relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith?

- Is it possible that John Smith never actually met Pocahontas?

- Was Smith's gunpowder accident actually a murder plot?

- How should we view John Smith's credibility overall?

- How was Pocahontas captured?

- Did Pocahontas willingly convert to Christianity?

- What should we make of Smith's "rescues" by so many women?

- Were Pocahontas and John Rolfe in love?

- What was the meaning of Pocahontas's final talk with John Smith?

- How did Pocahontas die?

- How did John Rolfe die?

- Was there a Powhatan prophecy?

- Why didnt the Indians wipe out the settlers?

- When did the balance of power shift from the Powhatans to the English?

- How big a part did European diseases play in the Jamestown story?

- Books

- Art

- Films

- Powhatan Tribes

- Links

- Site Map

- Contact

Is the Sedgeford Hall Portrait Evidence of a Crime?

Tsurumi Review, No. 51 - September 2021

By Kevin Miller

In the 1966 movie, Blow Up, a fashion photographer believed that an image on his roll of film contained clues to a murder. Some have claimed that the Sedgeford Hall Portrait likewise provides evidence of the sexual assault of an icon of American history.

|

Those who have never heard of the Sedgeford Hall Portrait (also known as the Heacham Hall Portrait) have probably seen it in a history book somewhere. For over 140 years it was considered by many to be a painting from life of Pocahontas and her son, Thomas Rolfe. Another image, an undisputed black and white engraving by Simon van de Passe, always lingered nearby, but that likeness, which had the benefit of verified authenticity, lacked warmth and color. Consequently, both the Sedgeford Hall Portrait and the Simon van de Passe engraving appeared in nearly every illustrated biography and children’s book about Pocahontas. Of the two portraits, the Sedgeford Hall Portrait has the more intriguing back story, and it has even been cited as evidence in a colonial era crime. |

The Sedgeford Hall Portrait’s artist was unknown, but some writers imagined that Pocahontas and Thomas must have sat for it in England in late 1616, just months before Pocahontas’s death.1 The Rolfe family once believed that John Rolfe, the English husband of Pocahontas, either brought the painting back to Virginia with him (while leaving his son in England) or sent for it later. Either way, the double portrait was said to have made the Atlantic crossing, vanished for a time, then returned to England by mysterious means.

In the latter decades of the 1800s, the trail became more documented. Eustace Neville Rolfe said she had purchased the portrait from a Mrs. Charlton (in 1875, according to one source), who claimed that “her husband had bought it in America years ago.”2 A plaque was attached to the frame, presumably by the Rolfes, stating in capital letters:

PRINCESS POCAHONTAS

Dau. of PRINCE POWHATTAN & 2nd WIFE of

JOHN ROLFE of HEACHAM (1585-1630)

b. 1595 m.1614 d. AT GRAVESEND 16173

Virginians became aware of a presumably authentic portrait of Pocahontas in England and offered to purchase it. In an 1875 letter, the Virginia Governor’s office posted a letter to the Rolfe family in Heacham with the message “The people of Virginia feel a strong desire to possess for preservation an accurate portrait of the Indian Princess, Pocahontas.”4 It is possible this message may have referred to other images of Pocahontas then in the possession of the Rolfes, but in any case, the Heacham Hall Portrait, so called because of the Rolfe property in which it then resided, was never acquired by the Commonwealth of Virginia.

In the latter decades of the 1800s, the trail became more documented. Eustace Neville Rolfe said she had purchased the portrait from a Mrs. Charlton (in 1875, according to one source), who claimed that “her husband had bought it in America years ago.”2 A plaque was attached to the frame, presumably by the Rolfes, stating in capital letters:

PRINCESS POCAHONTAS

Dau. of PRINCE POWHATTAN & 2nd WIFE of

JOHN ROLFE of HEACHAM (1585-1630)

b. 1595 m.1614 d. AT GRAVESEND 16173

Virginians became aware of a presumably authentic portrait of Pocahontas in England and offered to purchase it. In an 1875 letter, the Virginia Governor’s office posted a letter to the Rolfe family in Heacham with the message “The people of Virginia feel a strong desire to possess for preservation an accurate portrait of the Indian Princess, Pocahontas.”4 It is possible this message may have referred to other images of Pocahontas then in the possession of the Rolfes, but in any case, the Heacham Hall Portrait, so called because of the Rolfe property in which it then resided, was never acquired by the Commonwealth of Virginia.

|

Interestingly, the pearls worn by the woman in the portrait helped to bolster claims of the portrait’s authenticity and featured in a legend of their own. A pearl necklace had graced the neck of the Pocahontas character in Thomas Sully’s 1852 portrait, but that image had been created entirely from fantasy over 200 years after Pocahontas’s death. Nevertheless, an oral tradition arose that Pocahontas had been given a pearl necklace on her wedding day.5 The pearls in the Heacham Hall portrait then became purported evidence that the painting was an authentic likeness of Pocahontas. The pearl earrings from the portrait, too, materialized into an actual set of pearl earrings of unknown provenance that became prized relics handed down for a time by the Rolfe family, though they were later sold to a collector in New York.6

|

At some point, the Rolfes appear to have developed concerns about the Heacham Hall portrait. Art experts suggested that the painting dated from the 1700s,7 and a later estimate suggested the turn of the century (ca. 1800),8 making it less than 100 years old, compared to the over 250 years assumed when it was acquired. If correct, the portrait could not have been painted from life, though hope lingered that it had been copied from an authentic sketch or from a now lost original painting.

|

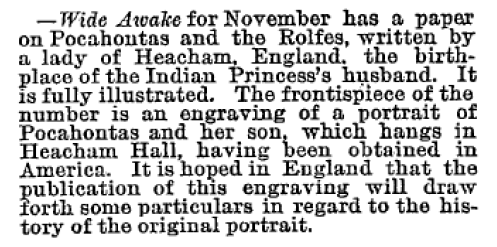

An attempt was made to gather some information about the portrait in America. In 1886, this notice appeared in the New York Times (Nov. 11):

|

Around 1900, the portrait was moved to Sedgeford Hall due to the sale of the Heacham property, and so the portrait became known as the Sedgeford Hall Portrait. In 1990, the painting was moved to its current location at King’s Lynn Town Hall in Norfolk, England.10

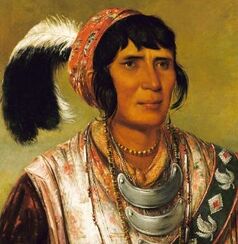

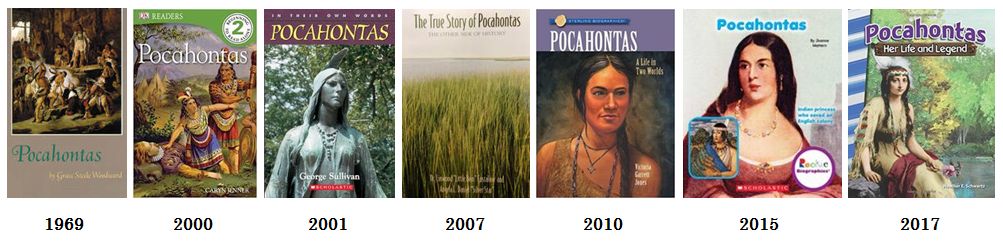

In the 20th Century, after images could be easily reproduced in published media, the Sedgeford Hall Portrait existed in limbo between authentic and disputed provenance. Nevertheless, numerous writers and publishers included the image in their Pocahontas-themed books. The portrait stood out for its realism and for how accessible it was compared to the Van de Passe engraving, which was cold and artificial with its formal English costuming, and which was too much of a departure from the prevailing concept of an American Indian. The Sedgeford Hall Portrait was especially valued for its depiction of Thomas, as no other image of him existed. His presence in the portrait may have helped viewers overlook the otherwise obvious fact that the woman in the portrait bore no resemblance to the Van de Passe Pocahontas.

Writers made commentaries on the Sedgeford Hall version of Pocahontas and her son that didn’t age well, as in these thoughts by reporter Vera Palmer from 1935 in the Richmond Times-Dispatch.11

Virginia resident authors Linwood Custalow and Angela Daniel, for their part, were certain of the authenticity of the portrait and that it offered proof of a crime. Noticing that Thomas looked much older than the not-quite two years of age he would have been if Pocahontas had married Rolfe in 1614, they claimed the portrait was evidence of rape and a cover-up, since Pocahontas had to have been impregnated well before her marriage for the child to be as old as depicted in 1616. They speculated in their book, The True Story of Pocahontas: the Other Side of History (2007), that the rapist could have been Sir Thomas Dale, since Dale and son Thomas shared the same given name.13

Sadly for that theory, but happily for Pocahontas, the portrait was revealed to have been misidentified all these years. It wasn’t Pocahontas and Thomas Rolfe at all, but actually Pe-o-ka, a wife of Seminole leader Osceola and their son. The actual story of the portrait was as fascinating as the mistaken one

In the 20th Century, after images could be easily reproduced in published media, the Sedgeford Hall Portrait existed in limbo between authentic and disputed provenance. Nevertheless, numerous writers and publishers included the image in their Pocahontas-themed books. The portrait stood out for its realism and for how accessible it was compared to the Van de Passe engraving, which was cold and artificial with its formal English costuming, and which was too much of a departure from the prevailing concept of an American Indian. The Sedgeford Hall Portrait was especially valued for its depiction of Thomas, as no other image of him existed. His presence in the portrait may have helped viewers overlook the otherwise obvious fact that the woman in the portrait bore no resemblance to the Van de Passe Pocahontas.

Writers made commentaries on the Sedgeford Hall version of Pocahontas and her son that didn’t age well, as in these thoughts by reporter Vera Palmer from 1935 in the Richmond Times-Dispatch.11

- There is something tremendously satisfying about the portrait, for it is filled with the mystery of the Indian people. Even the young Thomas seems to have been far more the son of his redskin mother than of his Anglo-Saxon father. Modern eugenists would answer, "Of course. Do not boys inherit from their mothers, girls from their father?" But these coldly scientific facts bothered nobody back in the early seventeenth century. (Palmer, 1935)

- The shy gladness with which the deep, dark eyes, almost living in their earnestness, look out from the canvas into one's very own, is more than maternal. I think she is feeling that the little hand which she clasps so closely in hers entitles her to be considered one with the nation she so loved and served; it is almost as though she would say, if the secret springs of her heart could find utterance, 'I too, am English now.' (Palmer, 1935)

Virginia resident authors Linwood Custalow and Angela Daniel, for their part, were certain of the authenticity of the portrait and that it offered proof of a crime. Noticing that Thomas looked much older than the not-quite two years of age he would have been if Pocahontas had married Rolfe in 1614, they claimed the portrait was evidence of rape and a cover-up, since Pocahontas had to have been impregnated well before her marriage for the child to be as old as depicted in 1616. They speculated in their book, The True Story of Pocahontas: the Other Side of History (2007), that the rapist could have been Sir Thomas Dale, since Dale and son Thomas shared the same given name.13

Sadly for that theory, but happily for Pocahontas, the portrait was revealed to have been misidentified all these years. It wasn’t Pocahontas and Thomas Rolfe at all, but actually Pe-o-ka, a wife of Seminole leader Osceola and their son. The actual story of the portrait was as fascinating as the mistaken one

|

Osceola (b. 1804), who had the English name Billy Powell, was Creek Indian on his mother’s side and English14 (some sources say Scottish15) on his father’s side and was raised Indian. He was the leader of Seminole resistance during the Second Seminole War until he was captured by a Florida contingent of the U.S. Army in 1837. His capture was controversial, as it occurred under a flag of truce during peace talks. Osceola was imprisoned, during which time his portrait was painted or sketched by at least three artists, George Catlin, W. M. Laning, and Robert John Curtis.16 It is believed that what later became known as the Sedgeford Hall Portrait was painted of Pe-o-ka, one of Osceola’s two wives, and the couple’s son, sometime around the time of Osceola’s death in captivity in 1838, though probably not by any of the three portrait artists named above. (Osceola’s other wife was called Che-cho-ter,17 but no portrait of her is known to exist.) The re-identification of the Sedgeford Hall Portrait as Pe-o-ka came about as follows.

|

In 2010, historian Bill Ryan, while researching Seminole history, came across a Victorian era magazine, Illustrated London News, published in 1848. In the magazine was a black and white engraved image that replicated what Ryan knew to be the Sedgeford Hall Portrait, though it didn’t have that name in 1848. This was the earliest documented evidence of the portrait. The image was identified as “The Wife and Child of Osceola the Last of the Seminole Indian Chiefs” and provided the name of the woman as Pe-o-ka.18

The text from the magazine reads:

The text from the magazine reads:

- “This picture, painted by a North American Indian artist, has lately been brought to London by Colonel Sherburne, who has applied, through the American representative here for a channel by which to present the painting to the queen. The picture portrays Pe-o-ka, the wife of Osceola, the principal War Chief of the Seminoles, in Florida, and her Son, on hearing of his treacherous capture under the white flag, his imprisonment, and death in a dungeon, by the American General, after a seven-years’ war with the Seminole tribe.”19

|

The reference to ‘a Native American Indian artist’ refers to a painter specializing in North American Indians as a subject, not to an actual Native American artist. The story of Osceola and his capture had been widely reported in England, and it is said that English sympathies were with the Indians. Further confirmation of the identification of the sitters as the wife and son of Osceola was found in Holden’s Dollar Magazine of 1850.20 For reasons unknown, the painting was never presented to the queen, as confirmed by the Royal Collection.21 |

The new identification was convincing and had the advantage of matching up better with the timing deduced by art experts. There was no possibility the Sedgeford Hall Portrait could have been painted during Pocahontas’s lifetime, but a likeness of Osceola’s wife, Pe-o-ka, done at a time when interest in Indian paintings had begun in earnest, made much more sense. It also removed the anachronism of Thomas’s advanced age in the final months of Pocahontas’s life.

After the painting had been brought to London, it would have then circulated in England for a number of years until it re-emerged in the possession of the mysterious Mrs. Charlton. She then either passed it off to the Rolfes as Pocahontas and Thomas or sold it to them unidentified. The Rolfes, hoping they had struck gold, believed for a time that they had found an authentic likeness of their famous ancestral relatives

After the painting had been brought to London, it would have then circulated in England for a number of years until it re-emerged in the possession of the mysterious Mrs. Charlton. She then either passed it off to the Rolfes as Pocahontas and Thomas or sold it to them unidentified. The Rolfes, hoping they had struck gold, believed for a time that they had found an authentic likeness of their famous ancestral relatives

|

The surviving descendants of the Rolfe family appear to have been satisfied with the 2010 re-identification of the portrait’s subjects, if perhaps a little disappointed. Less satisfied were the numerous authors and publishers who dearly wanted the portrait to be of Pocahontas and Thomas Rolfe. Many biographies and children’s books that had been published before 2010 still included this image, and amazingly, books published in 2015 and 2017, well after the re-identification, do so as well. And an illustration of Pocahontas based on the Sedgeford Hall image is literally set in stone at Historic Jamestowne in Virginia.22 |

The Sedgeford Hall Portrait may not be evidence of a crime, but it came about as a result of crimes when the U.S. Army captured Osceola during a truce and removed the Seminoles from their lands. For roughly 140 years, the portrait has been misidentified and continues to be, thanks to public fascination with Pocahontas over all other Native Americans. Osceola, the resistance leader of the Seminole Indians, along with his wife and son, deserve to be remembered. Perhaps continued attention to the re-identification of this portrait will be a small step in that direction.

Some of the books in publication today that include within their pages the Sedgeford Hall Portrait as an illustration of Pocahontas and Thomas

Some of the books in publication today that include within their pages the Sedgeford Hall Portrait as an illustration of Pocahontas and Thomas

Sources

(1) Allen, P. G. (2004). Pocahontas: Medicine Woman, Spy, Entrepreneur, Diplomat, Harper One, p. 294

(2) Palm Coast Observer (2011). “Palm Coast author solves 160-year 'Pocahontas' mystery”, http://www.palmcoastobserver.com/article/palm-coast-author-solves-160-year-pocahontas-mystery

(3) Pitcher, David. Borough Council of King's Lynn and West Norfolk, February 2016

(4) Dismore, J. (2015) “The Bones of Pocahontas,” The History Vault, April 2015. From a letter by S. Bassett French, dated Sept. 2, 1875 to Eustace Neville Rolfe from the Rolfe family archives.

(5) Custalow, L., Daniel, A. (2007). The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History. Fulcrum Publishing. p. 67, 70

(6) Palmer, V. Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 17, 1935

(7) Tilton, R. S. (1994). Pocahontas: the Evolution of an American Narrative, p. 108.

(8) Friends of King’s Lynn Museum Newsletter, Spring 2011, http://www.oldkingsroad.com/king's%20lynn/King's%20Lynn%202011.pdf

(9) The New York Times, “Literary Notes”, Nov. 11, 1886

(10) Pitcher, David. Borough Council of King's Lynn and West Norfolk, February 2016

(11) Palmer, V. Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 17, 1935

(12) Rex, C. (2015). Anglo-American Women Writers and Representations of Indianness, 1629-1824, p. 142

(13 Custalow, L., Daniel, A. (2007). The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History. Fulcrum Publishing. p. 64

(14) Wickman, P. R. (2006). Osceola’s Legacy, University of Alabama Press, p. 5

(15) Coe, C. H. (1939) The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 4, p. 304

(16) Wickman, P. R. (2006). Osceola’s Legacy, University of Alabama Press, p. 114

(17) Ibid, p. 54

(18) Friends of Kings Lynn Museum Newsletter, Spring 2011 http://www.oldkingsroad.com/king's%20lynn/King's%20Lynn%202011.pdf

(19) Ibid

(20) Holden’s Dollar Magazine, Vol 5-6, 1850 https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=jHxHAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA592&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false

(21) Friends of Kings Lynn Museum Newsletter, Spring 2011 http://www.oldkingsroad.com/king's%20lynn/King's%20Lynn%202011.pdf

(22) Pocahontas Lives! (2018) https://www.pocahontaslives.com/portraits.html

Illustrations

(1) Allen, P. G. (2004). Pocahontas: Medicine Woman, Spy, Entrepreneur, Diplomat, Harper One, p. 294

(2) Palm Coast Observer (2011). “Palm Coast author solves 160-year 'Pocahontas' mystery”, http://www.palmcoastobserver.com/article/palm-coast-author-solves-160-year-pocahontas-mystery

(3) Pitcher, David. Borough Council of King's Lynn and West Norfolk, February 2016

(4) Dismore, J. (2015) “The Bones of Pocahontas,” The History Vault, April 2015. From a letter by S. Bassett French, dated Sept. 2, 1875 to Eustace Neville Rolfe from the Rolfe family archives.

(5) Custalow, L., Daniel, A. (2007). The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History. Fulcrum Publishing. p. 67, 70

(6) Palmer, V. Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 17, 1935

(7) Tilton, R. S. (1994). Pocahontas: the Evolution of an American Narrative, p. 108.

(8) Friends of King’s Lynn Museum Newsletter, Spring 2011, http://www.oldkingsroad.com/king's%20lynn/King's%20Lynn%202011.pdf

(9) The New York Times, “Literary Notes”, Nov. 11, 1886

(10) Pitcher, David. Borough Council of King's Lynn and West Norfolk, February 2016

(11) Palmer, V. Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 17, 1935

(12) Rex, C. (2015). Anglo-American Women Writers and Representations of Indianness, 1629-1824, p. 142

(13 Custalow, L., Daniel, A. (2007). The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History. Fulcrum Publishing. p. 64

(14) Wickman, P. R. (2006). Osceola’s Legacy, University of Alabama Press, p. 5

(15) Coe, C. H. (1939) The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 4, p. 304

(16) Wickman, P. R. (2006). Osceola’s Legacy, University of Alabama Press, p. 114

(17) Ibid, p. 54

(18) Friends of Kings Lynn Museum Newsletter, Spring 2011 http://www.oldkingsroad.com/king's%20lynn/King's%20Lynn%202011.pdf

(19) Ibid

(20) Holden’s Dollar Magazine, Vol 5-6, 1850 https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=jHxHAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA592&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false

(21) Friends of Kings Lynn Museum Newsletter, Spring 2011 http://www.oldkingsroad.com/king's%20lynn/King's%20Lynn%202011.pdf

(22) Pocahontas Lives! (2018) https://www.pocahontaslives.com/portraits.html

Illustrations

- Sedgeford Hall Portrait, ca. 1837 (Figure 1) Borough Council of King's Lynn and West Norfolk

- Simon van de Passe portrait of Pocahontas, 1616 (Figure 2) public domain

- Thomas Sully portrait of Pocahontas, 1852 (Figure 3) Virginia Museum of History and Culture

- New York Times excerpt (Figure 4) New York Times, 1886

- George Catlin portrait of Osceola, 1838 (Figure 5) public domain

- Illustration (Figure 6) Holden’s Dollar Magazine, Vol 5-6, 1850 https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=jHxHAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA592&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Photo (Figure 7) Pocahontas Lives! (2018) https://www.pocahontaslives.com/portraits.html

- Book covers (Figure 8) Pocahontas Lives! (2018) https://www.pocahontaslives.com/portraits.html

(C) Tsurumi Review, No. 51; author, Kevin Miller 2021

Updated Oct. 31. 2021

Updated Oct. 31. 2021

- Home

- History

-

Controversies

- Controversies

- Is John Smith's account of his rescue by Pocahontas true?

- Did John Smith misunderstand a Powhatan 'adoption ceremony'?

- What was the relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith?

- Is it possible that John Smith never actually met Pocahontas?

- Was Smith's gunpowder accident actually a murder plot?

- How should we view John Smith's credibility overall?

- How was Pocahontas captured?

- Did Pocahontas willingly convert to Christianity?

- What should we make of Smith's "rescues" by so many women?

- Were Pocahontas and John Rolfe in love?

- What was the meaning of Pocahontas's final talk with John Smith?

- How did Pocahontas die?

- How did John Rolfe die?

- Was there a Powhatan prophecy?

- Why didnt the Indians wipe out the settlers?

- When did the balance of power shift from the Powhatans to the English?

- How big a part did European diseases play in the Jamestown story?

- Books

- Art

- Films

- Powhatan Tribes

- Links

- Site Map

- Contact