- Home

- History

-

Controversies

- Controversies

- Is John Smith's account of his rescue by Pocahontas true?

- Did John Smith misunderstand a Powhatan 'adoption ceremony'?

- What was the relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith?

- Is it possible that John Smith never actually met Pocahontas?

- Was Smith's gunpowder accident actually a murder plot?

- How should we view John Smith's credibility overall?

- How was Pocahontas captured?

- Did Pocahontas willingly convert to Christianity?

- What should we make of Smith's "rescues" by so many women?

- Were Pocahontas and John Rolfe in love?

- What was the meaning of Pocahontas's final talk with John Smith?

- How did Pocahontas die?

- How did John Rolfe die?

- Was there a Powhatan prophecy?

- Why didnt the Indians wipe out the settlers?

- When did the balance of power shift from the Powhatans to the English?

- How big a part did European diseases play in the Jamestown story?

- Books

- Art

- Films

- Powhatan Tribes

- Links

- Site Map

- Contact

What was the relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith?

- "Legend - and even worse, the Disney cartoon - speaks of a love affair between Pocahontas and John Smith; many Americans today actually believe that he was her second , English husband. There is no historical evidence at all for such a thing." (p. 142) - Rountree (2005) Pocahontas, Powhatan, Opechancanough: Three Indian Lives Changed by Jamestown

____________

Terrence Malick's 'The New World'

Terrence Malick's 'The New World'

The idea that there was a romance between Pocahontas and John Smith has been around since the early 1800s, if not earlier. John Davis's publications, Travels in the United States of America and Captain Smith and Princess Pocahontas: an Indian tale, (1805) may have been the source of the apocryphal romance. Robert S. Tilton (Pocahontas: The Evolution of an American Narrative, 1994) said of Davis,

From that beginning, the love story angle really took off and had a 200-year run leading up to the 1995 Disney animated movie, Pocahontas, and the 2005 Terrence Malick movie, The New World, with Colin Farrell as an irresistible John Smith. But those movies are for entertainment purposes, and we should not expect to find within them a definitive response to the historical question of a romance that has stoutly resisted an answer for centuries. Today, historians may insist there was no romance, but since we can’t be 100% sure, movie-makers will always go with the most compelling story. That some Native Americans and a handful of ethnohistorians have a different opinion has so far not presented a roadblock to producers who smell a hit.

To be clear, historians today generally reject the idea of a romance between Pocahontas and John Smith. They usually point out the age gap - Pocahontas was about 11-13 during the two years of their interaction, while John Smith was around 28-30 during that time span. More to the point, there were no specific mentions of a romance in the words of the original chroniclers, and we certainly don’t have any words from Pocahontas on the matter (or any matter, unfortunately)..

However, many people interested in Pocahontas today are apt to be open to the idea of a romance largely because the movies present the story that way. And depending on which book on Pocahontas you open, and how old it is, the possibility of a romance is either weakened or strengthened by the imagination of the author.. Estimates of Pocahontas's age in books vary widely, ranging from 8 to 14, depending on the teller and how badly they want a romance to appear possible. John Davis, referenced above, made her 14, of which Tilton wrote, "He makes her fourteen to leave no doubt that a romantic attraction prompted her actions." p. 43. Frances Mossiker, whose 1976 book was THE Pocahontas biography for decades, also liked the idea of a romance. She cited Pocahontas’s participation in the fertility dance as evidence that Pocahontas had already reached puberty, which would make her of marriageable age. More recently, anthropologist Helen Rountree (2005) stated there was no evidence for., a romance” (p. 142).. Camilla Townsend (2004) suggested that Smith had sexual thoughts for Pocahontas, but that she would have had no romantic feelings for him (p. 76). James Horn (2005) dismissed a Smith-Pocahontas relationship as “overblown mythology.” p. 288.

While I favor the “no romance” answer to the question, I will nevertheless investigate the recorded information in detail and try to analyze what we know. Read on for author comments and for the complete story as told by John Smith himself. My conclusions about the possibility of a romance are near the bottom of the page.

- [John Davis] ... first recognized the potential of the narrative to be the germ of a great romance. Davis is also the first to subordinate Pocahontas's relationship with Rolfe to her more dramatic tie to Smith, and to posit that it was her love for the captain that accounted for her heroism. Tilton, p. 3

From that beginning, the love story angle really took off and had a 200-year run leading up to the 1995 Disney animated movie, Pocahontas, and the 2005 Terrence Malick movie, The New World, with Colin Farrell as an irresistible John Smith. But those movies are for entertainment purposes, and we should not expect to find within them a definitive response to the historical question of a romance that has stoutly resisted an answer for centuries. Today, historians may insist there was no romance, but since we can’t be 100% sure, movie-makers will always go with the most compelling story. That some Native Americans and a handful of ethnohistorians have a different opinion has so far not presented a roadblock to producers who smell a hit.

To be clear, historians today generally reject the idea of a romance between Pocahontas and John Smith. They usually point out the age gap - Pocahontas was about 11-13 during the two years of their interaction, while John Smith was around 28-30 during that time span. More to the point, there were no specific mentions of a romance in the words of the original chroniclers, and we certainly don’t have any words from Pocahontas on the matter (or any matter, unfortunately)..

However, many people interested in Pocahontas today are apt to be open to the idea of a romance largely because the movies present the story that way. And depending on which book on Pocahontas you open, and how old it is, the possibility of a romance is either weakened or strengthened by the imagination of the author.. Estimates of Pocahontas's age in books vary widely, ranging from 8 to 14, depending on the teller and how badly they want a romance to appear possible. John Davis, referenced above, made her 14, of which Tilton wrote, "He makes her fourteen to leave no doubt that a romantic attraction prompted her actions." p. 43. Frances Mossiker, whose 1976 book was THE Pocahontas biography for decades, also liked the idea of a romance. She cited Pocahontas’s participation in the fertility dance as evidence that Pocahontas had already reached puberty, which would make her of marriageable age. More recently, anthropologist Helen Rountree (2005) stated there was no evidence for., a romance” (p. 142).. Camilla Townsend (2004) suggested that Smith had sexual thoughts for Pocahontas, but that she would have had no romantic feelings for him (p. 76). James Horn (2005) dismissed a Smith-Pocahontas relationship as “overblown mythology.” p. 288.

While I favor the “no romance” answer to the question, I will nevertheless investigate the recorded information in detail and try to analyze what we know. Read on for author comments and for the complete story as told by John Smith himself. My conclusions about the possibility of a romance are near the bottom of the page.

Journalist David A. Price (2003) described their relationship thus:

These lines are merely speculation on Price's part, but they're not unreasonable.

- "If [Pocahontas] had originally pictured [Smith] as a captive servant who would spend his days making her beads and jewelry, their relationship had evolved to give her something of greater value: friendship with someone who shared her inquisitive sensibility. She was curious about the English, and she enjoyed being among them; in Smith, she had found an Englishman who could speak her language and requite her curiosity about the foreigners. Although Smith had practical reasons to encourage the visits--honing his Algonquian, maintaining lines of communication with an ally in Powhatan's court--he also formed an admiration for the 'nonpareil' and took an avuncular interest in her." Love & Hate in Jamestown, p. 77

These lines are merely speculation on Price's part, but they're not unreasonable.

Camilla Townsend, in Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma (2004), writes of Smith's possible sexual interest in Pocahontas and even hints at possible abuse. She writes:

On the point of Smith being able to sleep with Pocahontas if he had so desired, the relevant quote is "If he would he might have married her, or have done what him listed. For there was none that could have hindered his determination." p. 75 (Townsend), from The Proceedings of the English Colonie in Virginia. This quote is said to have come from friends of John Smith (Richard Pots, William Phettiplace), but the documents are also presumed to have been edited by Smith himself.

On the point of lewd comments and possible abuse, the relevant quote is "So diligent were they in this business [i.e., charges against Smith], that what any could remember, hee had ever done, or said, in mirth, or passion, by some circumstantial oath, it was applied to their fittest use ... I have presumed to say this much in his behalfe for that I never heard such foule slanders ..." p. 76 (Townsend), also from the Proceedings.

Townsend gives credit to Rebecca Faery (Cartographies of Desire, 1999) for Faery's analysis of the "sexual innuendo" found in the Proceedings.

The text of the Proceedings can be found in The Complete Works of Captain John Smith at Virtual Jamestown.

{The Proceedings link is temporarily unavailable; sorry. - 11/3/2021}

- "He claimed that if he had wanted to marry Pocahontas, or to sleep with her, he would have done so, as absolutely no one could have stopped him--including Pocahontas herself, presumably. His own--or his friends'--summary of the council's investigation openly acknowledged that he had made lewd comments about her--or had even done things to her--in jokes ('mirth'), or in moments of sexual arousal ('passion'). Perhaps that is why, even as he reminded the people to whom he was defending himself that she was only a child, not yet fit for marriage, he raised her age by a good three years. Suddenly she was "no more than thirteen or fourteen" at the time, instead of her actual ten or eleven." p. 76

On the point of Smith being able to sleep with Pocahontas if he had so desired, the relevant quote is "If he would he might have married her, or have done what him listed. For there was none that could have hindered his determination." p. 75 (Townsend), from The Proceedings of the English Colonie in Virginia. This quote is said to have come from friends of John Smith (Richard Pots, William Phettiplace), but the documents are also presumed to have been edited by Smith himself.

On the point of lewd comments and possible abuse, the relevant quote is "So diligent were they in this business [i.e., charges against Smith], that what any could remember, hee had ever done, or said, in mirth, or passion, by some circumstantial oath, it was applied to their fittest use ... I have presumed to say this much in his behalfe for that I never heard such foule slanders ..." p. 76 (Townsend), also from the Proceedings.

Townsend gives credit to Rebecca Faery (Cartographies of Desire, 1999) for Faery's analysis of the "sexual innuendo" found in the Proceedings.

The text of the Proceedings can be found in The Complete Works of Captain John Smith at Virtual Jamestown.

{The Proceedings link is temporarily unavailable; sorry. - 11/3/2021}

Native American writer Paul Gunn Allen (2003), referring specifically to Pocahontas's words at her final meeting in England with John Smith, wrote:

My comment:

I don't disagree with Gunn Allen on her main point, and her comment conforms to current historical thinking on this matter. However, I don't understand why she accuses John Smith of thinking Pocahontas was reacting out of romantic pique; there's nothing in his writings to imply such a thing. She's on firmer ground in her accusation against "later writers."

- "There is nothing in Pocahontas's remarks that refers, however tangentially, to romantic love. (p. 293). ... That anyone, either Smith or later writers, could mistake her accusations as words of anger felt by a woman scorned is one of the puzzles of the Pocahontas story in American cultural lore." (p. 294). - Paula Gunn Allen (2003), Pocahontas: Medicine Woman - Spy - Entrepreneur - Diplomat

My comment:

I don't disagree with Gunn Allen on her main point, and her comment conforms to current historical thinking on this matter. However, I don't understand why she accuses John Smith of thinking Pocahontas was reacting out of romantic pique; there's nothing in his writings to imply such a thing. She's on firmer ground in her accusation against "later writers."

In search of romance: analysis of all John Smith writings that mention Pocahontas

John Smith was a prolific writer in his later years, but he wrote in detail mainly about his exploits as a soldier and explorer. As fate would have it, readers some centuries down the road cared less for his tales of adventure than for the few lines he dropped that suggested the possibility of a relationship between himself and Pocahontas. Smith never actually explained their relationship, but every mention of her by Smith has been analyzed for clues, with far-ranging results. Theories have ranged from “Smith never actually met Pocahontas; he just dropped her name to bask in her reflected glory” to “they were friends and language tutors to each other” to “they were lovers” to “Smith was a child abuser.” We will, of course, never know with certainty what their relationship, if they had one, was like. The best we can do is look at the specific mentions of Pocahontas and see what possible interpretations we can glean from them and what conclusions historians have reached based on the thin evidence.

In the paragraphs below, I list all mentions of Pocahontas by John Smith in the order they were published and look for suggestions of a romance between them. Note that the Letter to Queen Anne (1616/1624) is listed earlier than The Generall Historie (1624) on the assumption that it was written and sent to the queen in 1616 (according to Smith), although it was actually published in 1624. My conclusions are at the bottom of the page, following the quotations from Smith.

A True Relation, 1608

First, we should not doubt that Smith knew Pocahontas, as Smith was the first person in recorded history to mention her in A True Relation, 1608.

[I should mention here the theory that there was more than one Pocahontas. Daniel Richter (2001) wrote: "...'Pocahontas' was a nickname, or even just a descriptive term, meaning something to the effect of 'playful one' or 'mischievous girl.' It is possible, therefore, that not every Pocahontas they mention was the one who later became famous." (p. 70) Facing East from Indian Country. We should note, however, that while it's reasonable there was more than one Pocahontas, just like there's more than one John Smith in the world, we have no idea if Richter has even read Smith's writings and if he can point out which mention of her could reasonably be a separate person. Having read Smith myself, I don't believe there was any confusion about who he was writing about.]

[Re. whether the True Relation mention above is the actual first mention of Pocahontas, Philip Barbour (1986), states “This is the first mention of Pocahontas in the True Relation as it was printed, but the casual way in which her name appears on the next page suggests that Smith's original letter had mentioned her before.” – The Complete Works, footnote 237. In other words, Barbour is suggesting the possibility that Smith had written more about her, but the reference or references were deleted.]

Looking at Smith’s words, what can we imagine about their “relationship”? In the 1608 mention, Smith was describing the arrival of Pocahontas (most likely in the company of warrior bodyguards, including the messenger, Rawhunt) to Jamestown to secure the release of the Indian prisoners the colonists held there. Smith commented first on her physical beauty and bearing, saying that her features, countenance (i.e., her expression and composure) and proportion (her body?) were exceptional compared to others. He then added that she had wit and spirit, i.e., charisma, that made her stand out above all of her people. (All this in a girl of about 11!)

There are several ways to look at these comments by Smith. From what we know of the entire body of Smith’s writings, we notice that he mainly stuck to the facts of what happened (as he remembered and chose to tell them) to provide a chronicle of events, and he almost never paused to admire women gratuitously in his writing. (He did, however, describe the queen of Appomattoc as “a comely young salvage” in A True Relation) These comments may have been Smith simply stating the reality as he saw it before him. In other words, Pocahontas was exceptional, and Smith was merely recording the fact of it. Another possibility is that Smith had some degree of attraction to Pocahontas, despite her being only 11. He noticed her, admired her, and his interest in her was inadvertently revealed in this rare mention of an attractive female, perhaps a child who had developed in advance of her years. Thirdly, there is the possibility that Smith was describing a consensus of opinion by fellow settlers. For example, if there was a general buzz in the all-male colony about the arrival of Pocahontas, Smith may have ridden the wave of their shared observations.

In any case, this meeting of Pocahontas and John Smith was for the business of negotiating a release of prisoners in the company of Rawhunt, and there was likely no opportunity for them to develop a relationship of any sort beyond establishing a diplomatic relationship, or possibly deepening one that had been started when Smith had been held prisoner.

And that brings up the next point, which is that this meeting, while the first known mention by Smith in his writings, may not have been the first time Smith had met Pocahontas. While we can’t say with any certainty that Pocahontas actually played a role in the legendary (possibly mythical) rescue of Smith, we do know that Smith had been held prisoner by the Powhatans for about a month. During that time, Smith could have encountered Pocahontas, and they may have established a connection of some sort at that time. That there was such a connection is suggested by the choice of Pocahontas as the emissary sent by Powhatan to secure the release of the prisoners. Some writers have described the arrival of Pocahontas as a reminder to Smith that he owed Pocahontas and Powhatan a debt (i.e., the rescue).

Camilla Townsend (Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma, 2004) believes that Smith had met Pocahontas earlier::

Going back to the meeting at Jamestown, Smith’s first known mention of Pocahontas, his words regarding her continue as follows (from A True Relation):

The following sentences conclude this first mention of Pocahontas in A True Relation:

A Map of Virginia, 1612

The next mention of Pocahontas comes in Smith’s 1612 publication, A Map of Virginia. He includes a list of Powhatan words as well as a few sentences in a glossary (“Because many doe desire to knowe the maner of their language, I have inserted these few words.”) Buried at the end of the list, Smith hints at spending time with Pocahontas in an effort to learn her language:

I am not certain that this really shows how Smith thought of Pocahontas, but it does hint at a friendly relationship, and possibly one that included mutual language tutoring. From a more sinister perspective, and one that could probably only come from a presentist 21st Century outlook, this scenario could hint at a weird uncle relationship, a la Lewis Carroll/Alice Liddell. However, that would require far too much supposition, and since Smith included the phrase as a simple example of Powhatan language,and we have no particular evidence to view it otherwise, I see no reason to blow this mention of Pocahontas out of proportion.

One unfortunate problem with this sentence is that it doesn’t indicate when the encounter with Pocahontas (if there was one) occurred. Was it during Smith’s captivity? During a visit by Pocahontas to Jamestown? On one of Smith’s excursions up the river? There’s no way of knowing.

The Proceedings, 1612

The next mention of Pocahontas by Smith in his writings comes in The Proceedings when the incident above of Pocahontas coming to Jamestown to secure the release of the Indian prisoners is repeated, though much more briefly (and interestingly, with no mention of the chief negotiator, Rawhunt).

[It is worth noting that these three early writings by Smith (A True Relation, Map of Virginia, and The Proceedings), in addition to not mentioning a rescue by Pocahontas during Smith’s captivity, also fail to mention Pocahontas being present at the naked fertility dance. Smith’s later writings would add her to that incident.]

The next mention of Pocahontas is a significant one for its implications of a relationship between Smith and Pocahontas. It comes in The Proceedings (1612), but in a section with uncertain authorship. Richard Pots and William Phettiplace, friends of Smith, are listed as the chapter's authors, but John Smith is presumed to have had a hand in its editing. The passage from which the following sentences come is essentially a defense of Smith's actions in Jamestown and a rebuttal to accusations of wrongdoing by Smith's enemies. The relevant passage is as follows:

These sentences, and those that immediately follow, contain much fodder for speculation. First, it states that at least one contemporary of John Smith (but we may assume others too) suspected Smith of being in a position to marry Pocahontas, and that she was indeed exceptional enough among the Indians that such an idea would have been reasonable, had it been true. The writers then suggest it was not true, given her age of 13 or 14, presumably too young for Smith (despite being several years older than Smith's own estimate of 10 in True Relation). This denial (if it was one) is weak in its wording, but even weaker considering that an age of 13-14 would make Pocahontas old enough to be married off by the Powhatans. (Rountree (2005) wrote, "They helped along the fantasy they were contradicting by adding a couple of years to her age" p. 142). In short, these sentences, while offering no proof of a relationship. open the door to the possibility of one, and state that the idea of a potential marriage between them existed in the earliest days of the Jamestown colony.

The passage then states that Pocahontas often came to the fort with provisions (the first mention of Pocahontas being involved in this), and that the provisions were specifically for Smith (presumably on Powhatan's orders). The passage states that Smith very much respected Pocahontas, and that she certainly deserved it, having risked her life to warn Smith of a plot by Powhatan against his life. These sentences seem to explain why Smith had a special place in his heart for Pocahontas, and that his feelings were reasonable considering the extraordinary services Pocahontas rendered to Smith and the colony.

These sentences are particularly interesting for being the first mention by Smith (and/or Pots/Phettiplace) of Pocahontas's visit in the night to warn Smith of a plot against him and his men. Some have described this as a second (but first in terms of appearance in the writings) rescue of John Smith. This story, while not as dramatic as the legendary rescue from head bashing at Werowocomoco, has the benefit of vague corroboration by Pots and Phettiplace. We can't necessarily place them at the scene, but we at least have their names on the document, and these two were presumably alive at publication. This is in contrast with Thomas Studley, who was already too dead to have authored the passage in The Proceedings he was given credit for.

The passage in The Proceedings continues as follows:

This section is the meat of the defense of John Smith, stating that he would not have inherited the Powhatan empire had he married Pocahontas, as she was not in line to succeed Powhatan. While this is a good point, we should notice that Thomas Rolfe, the son of John Rolfe and Pocahontas, inherited a large piece of property that is said to have come from Powhatan. Smith would have doubtless been granted some amount of land had he married Pocahontas. Instead, he returned to England empty handed. The part that begins "nor was it ever suspected hee had ever such a thought ..." is Smith and his friends denying that Smith had any intention to marry her, and in fact, his thoughts about her were always pure and discrete. Not everyone today believes these words (see Townsend above), but this is the closest we'll ever get to hearing John Smith's thoughts on the issue.

The passage in defense of Smith continues:

These sentences are interesting, as they say that Smith could have married her if had so desired, but he chose not to. The words "...or have done what him listed" are loaded with implication. They could imply that Smith had had opportunities for sexual relations with Pocahontas, either consensual or otherwise. On the other hand, since we can't assume the writing was done with extreme care and attention to implication, the words may simply be repeating the previous point, that he could have married Pocahontas regardless of who objected.

The passage continues:

The lines "... what any could remember hee had ever done or said in mirth or passion by some circumstantiall oath ..." are also interesting and filled with implication. Townsend (2004, p. 75, 76) seems to read into them a kind of confession that Smith had sexually assaulted or abused Pocahontas. While I recognize that possibility, I also think we should consider these words with the presumed intent they were written, which was to defend Smith from allegations. They may be saying, "Hey, Smith joked about a lot of things like all soldiers do, but let's not take that too seriously" or something to that effect. They then say clearly that the accusations against Smith are false.

The passage continues with denials of any wrongdoing by Smith:

There is no mention of Pocahontas in these lines, but we are advised that all negative claims against Smith (including, presumably, those involving Pocahontas) were motivated by the desire of Smith's enemies in Jamestown to bring dishonor and disfavor upon him. With hindsight, we know this was to ensure that Smith never returned to Jamestown or had any further influence on the company or Jamestown affairs.

John Smith was a prolific writer in his later years, but he wrote in detail mainly about his exploits as a soldier and explorer. As fate would have it, readers some centuries down the road cared less for his tales of adventure than for the few lines he dropped that suggested the possibility of a relationship between himself and Pocahontas. Smith never actually explained their relationship, but every mention of her by Smith has been analyzed for clues, with far-ranging results. Theories have ranged from “Smith never actually met Pocahontas; he just dropped her name to bask in her reflected glory” to “they were friends and language tutors to each other” to “they were lovers” to “Smith was a child abuser.” We will, of course, never know with certainty what their relationship, if they had one, was like. The best we can do is look at the specific mentions of Pocahontas and see what possible interpretations we can glean from them and what conclusions historians have reached based on the thin evidence.

In the paragraphs below, I list all mentions of Pocahontas by John Smith in the order they were published and look for suggestions of a romance between them. Note that the Letter to Queen Anne (1616/1624) is listed earlier than The Generall Historie (1624) on the assumption that it was written and sent to the queen in 1616 (according to Smith), although it was actually published in 1624. My conclusions are at the bottom of the page, following the quotations from Smith.

A True Relation, 1608

First, we should not doubt that Smith knew Pocahontas, as Smith was the first person in recorded history to mention her in A True Relation, 1608.

- "Powhatan, understanding we detained certaine Salvages, sent his Daughter, a child of tenne yeares old: which, not only for feature, countenance, and proportion, much exceedeth any of the rest of his people: but for wit and spirit, the only Nonpariel of his Country."

[I should mention here the theory that there was more than one Pocahontas. Daniel Richter (2001) wrote: "...'Pocahontas' was a nickname, or even just a descriptive term, meaning something to the effect of 'playful one' or 'mischievous girl.' It is possible, therefore, that not every Pocahontas they mention was the one who later became famous." (p. 70) Facing East from Indian Country. We should note, however, that while it's reasonable there was more than one Pocahontas, just like there's more than one John Smith in the world, we have no idea if Richter has even read Smith's writings and if he can point out which mention of her could reasonably be a separate person. Having read Smith myself, I don't believe there was any confusion about who he was writing about.]

[Re. whether the True Relation mention above is the actual first mention of Pocahontas, Philip Barbour (1986), states “This is the first mention of Pocahontas in the True Relation as it was printed, but the casual way in which her name appears on the next page suggests that Smith's original letter had mentioned her before.” – The Complete Works, footnote 237. In other words, Barbour is suggesting the possibility that Smith had written more about her, but the reference or references were deleted.]

Looking at Smith’s words, what can we imagine about their “relationship”? In the 1608 mention, Smith was describing the arrival of Pocahontas (most likely in the company of warrior bodyguards, including the messenger, Rawhunt) to Jamestown to secure the release of the Indian prisoners the colonists held there. Smith commented first on her physical beauty and bearing, saying that her features, countenance (i.e., her expression and composure) and proportion (her body?) were exceptional compared to others. He then added that she had wit and spirit, i.e., charisma, that made her stand out above all of her people. (All this in a girl of about 11!)

There are several ways to look at these comments by Smith. From what we know of the entire body of Smith’s writings, we notice that he mainly stuck to the facts of what happened (as he remembered and chose to tell them) to provide a chronicle of events, and he almost never paused to admire women gratuitously in his writing. (He did, however, describe the queen of Appomattoc as “a comely young salvage” in A True Relation) These comments may have been Smith simply stating the reality as he saw it before him. In other words, Pocahontas was exceptional, and Smith was merely recording the fact of it. Another possibility is that Smith had some degree of attraction to Pocahontas, despite her being only 11. He noticed her, admired her, and his interest in her was inadvertently revealed in this rare mention of an attractive female, perhaps a child who had developed in advance of her years. Thirdly, there is the possibility that Smith was describing a consensus of opinion by fellow settlers. For example, if there was a general buzz in the all-male colony about the arrival of Pocahontas, Smith may have ridden the wave of their shared observations.

In any case, this meeting of Pocahontas and John Smith was for the business of negotiating a release of prisoners in the company of Rawhunt, and there was likely no opportunity for them to develop a relationship of any sort beyond establishing a diplomatic relationship, or possibly deepening one that had been started when Smith had been held prisoner.

And that brings up the next point, which is that this meeting, while the first known mention by Smith in his writings, may not have been the first time Smith had met Pocahontas. While we can’t say with any certainty that Pocahontas actually played a role in the legendary (possibly mythical) rescue of Smith, we do know that Smith had been held prisoner by the Powhatans for about a month. During that time, Smith could have encountered Pocahontas, and they may have established a connection of some sort at that time. That there was such a connection is suggested by the choice of Pocahontas as the emissary sent by Powhatan to secure the release of the prisoners. Some writers have described the arrival of Pocahontas as a reminder to Smith that he owed Pocahontas and Powhatan a debt (i.e., the rescue).

Camilla Townsend (Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma, 2004) believes that Smith had met Pocahontas earlier::

- "That John Smith got to know Pocahontas at least a little during his days in Werowocomoco seems beyond doubt. She lived there, and her later life proved her to be both outgoing and curious. ... When she later made a brief appearance of only a few hours at the English fort, Smith called her 'the nonpareil of her country' in the report he sent home immediately afterward. If she had been a gorgeous fifteen-year-old, he might--for obvious reasons--have needed only a few minutes to decide that was what he thought of her; but he would not have come to such a judgement of a ten-year-old so immediately without any previous acquaintance." p. 59

Going back to the meeting at Jamestown, Smith’s first known mention of Pocahontas, his words regarding her continue as follows (from A True Relation):

- "He [Rawhunt, a Powhatan messenger] with a long circumstance told mee how well Powhatan loved and respected mee, and in that I should not doubt any way of his kindnesse, he had sent his child, which he most esteemed, to see me, a Deere and bread besides for a present: desiring me that the Boy might come againe, which he loved exceedingly, his litle Daughter hee had taught this lesson also: not taking notice at all of the Indeans that had beene prisoners three daies, till that morning that she saw their fathers and friends come quietly, and in good tearmes to entreate their libertie."

The following sentences conclude this first mention of Pocahontas in A True Relation:

- "In the afternoone, they being gone, we guarded them as before to the Church, and after prayer, gave them to Pocahuntas, the Kings Daughter, in regard of her fathers kindnesse in sending her: after having well fed them, as all the time of their imprisonment, we gave them their bowes, arrowes, or what else they had, and with much content, sent them packing: Pocahuntas also we requited, with such trifles as contented her, to tel that we had used the Paspaheyans very kindly in so releasing them. "

A Map of Virginia, 1612

The next mention of Pocahontas comes in Smith’s 1612 publication, A Map of Virginia. He includes a list of Powhatan words as well as a few sentences in a glossary (“Because many doe desire to knowe the maner of their language, I have inserted these few words.”) Buried at the end of the list, Smith hints at spending time with Pocahontas in an effort to learn her language:

- "Kekaten pokahontas patiaquagh niugh tanks manotyens neer mowchick rawrenock audowgh Bid Pokahontas bring hither two little Baskets, and I wil give her white beads to make her a chaine.."

I am not certain that this really shows how Smith thought of Pocahontas, but it does hint at a friendly relationship, and possibly one that included mutual language tutoring. From a more sinister perspective, and one that could probably only come from a presentist 21st Century outlook, this scenario could hint at a weird uncle relationship, a la Lewis Carroll/Alice Liddell. However, that would require far too much supposition, and since Smith included the phrase as a simple example of Powhatan language,and we have no particular evidence to view it otherwise, I see no reason to blow this mention of Pocahontas out of proportion.

One unfortunate problem with this sentence is that it doesn’t indicate when the encounter with Pocahontas (if there was one) occurred. Was it during Smith’s captivity? During a visit by Pocahontas to Jamestown? On one of Smith’s excursions up the river? There’s no way of knowing.

The Proceedings, 1612

The next mention of Pocahontas by Smith in his writings comes in The Proceedings when the incident above of Pocahontas coming to Jamestown to secure the release of the Indian prisoners is repeated, though much more briefly (and interestingly, with no mention of the chief negotiator, Rawhunt).

- “… he sent his messengers and his dearest Daughter Pocahuntas to excuse him, of the injuries done by his subjects, desiring their liberties, with the assurance of his love. After Smith had given the prisoners what correction hee thought fit, used them well a day or two after, and then delivered them Pocahuntas, for whose sake only he fained to save their lives and graunt them liberty.”

[It is worth noting that these three early writings by Smith (A True Relation, Map of Virginia, and The Proceedings), in addition to not mentioning a rescue by Pocahontas during Smith’s captivity, also fail to mention Pocahontas being present at the naked fertility dance. Smith’s later writings would add her to that incident.]

The next mention of Pocahontas is a significant one for its implications of a relationship between Smith and Pocahontas. It comes in The Proceedings (1612), but in a section with uncertain authorship. Richard Pots and William Phettiplace, friends of Smith, are listed as the chapter's authors, but John Smith is presumed to have had a hand in its editing. The passage from which the following sentences come is essentially a defense of Smith's actions in Jamestown and a rebuttal to accusations of wrongdoing by Smith's enemies. The relevant passage is as follows:

- "Some propheticall spirit calculated hee had the Salvages in such subjection, hee would have made himselfe a king, by marrying Pocahontas, Powhatan's daughter. It is true she was the very nomparell of his kingdome, and at most not past 13 or 14 yeares of age. Very oft she came to our fort, with what she could get for Captaine Smith, that ever loved and used the Countrie well, but her especially he ever much respected: and she so well requited it, that when her father intended to have surprised him, shee by stealth in the darke night came through the wild woods and told him of it. .." from Horn (2007) p. 113.

These sentences, and those that immediately follow, contain much fodder for speculation. First, it states that at least one contemporary of John Smith (but we may assume others too) suspected Smith of being in a position to marry Pocahontas, and that she was indeed exceptional enough among the Indians that such an idea would have been reasonable, had it been true. The writers then suggest it was not true, given her age of 13 or 14, presumably too young for Smith (despite being several years older than Smith's own estimate of 10 in True Relation). This denial (if it was one) is weak in its wording, but even weaker considering that an age of 13-14 would make Pocahontas old enough to be married off by the Powhatans. (Rountree (2005) wrote, "They helped along the fantasy they were contradicting by adding a couple of years to her age" p. 142). In short, these sentences, while offering no proof of a relationship. open the door to the possibility of one, and state that the idea of a potential marriage between them existed in the earliest days of the Jamestown colony.

The passage then states that Pocahontas often came to the fort with provisions (the first mention of Pocahontas being involved in this), and that the provisions were specifically for Smith (presumably on Powhatan's orders). The passage states that Smith very much respected Pocahontas, and that she certainly deserved it, having risked her life to warn Smith of a plot by Powhatan against his life. These sentences seem to explain why Smith had a special place in his heart for Pocahontas, and that his feelings were reasonable considering the extraordinary services Pocahontas rendered to Smith and the colony.

These sentences are particularly interesting for being the first mention by Smith (and/or Pots/Phettiplace) of Pocahontas's visit in the night to warn Smith of a plot against him and his men. Some have described this as a second (but first in terms of appearance in the writings) rescue of John Smith. This story, while not as dramatic as the legendary rescue from head bashing at Werowocomoco, has the benefit of vague corroboration by Pots and Phettiplace. We can't necessarily place them at the scene, but we at least have their names on the document, and these two were presumably alive at publication. This is in contrast with Thomas Studley, who was already too dead to have authored the passage in The Proceedings he was given credit for.

The passage in The Proceedings continues as follows:

- "But her marriage could no way have intitled him by any right to the kingdome, nor was it ever suspected hee had ever such a thought, or more regarded her, or any of them, then in honest reason, and discretion he might." from Horn (2007), p. 113.

This section is the meat of the defense of John Smith, stating that he would not have inherited the Powhatan empire had he married Pocahontas, as she was not in line to succeed Powhatan. While this is a good point, we should notice that Thomas Rolfe, the son of John Rolfe and Pocahontas, inherited a large piece of property that is said to have come from Powhatan. Smith would have doubtless been granted some amount of land had he married Pocahontas. Instead, he returned to England empty handed. The part that begins "nor was it ever suspected hee had ever such a thought ..." is Smith and his friends denying that Smith had any intention to marry her, and in fact, his thoughts about her were always pure and discrete. Not everyone today believes these words (see Townsend above), but this is the closest we'll ever get to hearing John Smith's thoughts on the issue.

The passage in defense of Smith continues:

- "If he would he might have married her, or have done what him listed. For there was none that could have hindred his determination." Horn, p. 113

These sentences are interesting, as they say that Smith could have married her if had so desired, but he chose not to. The words "...or have done what him listed" are loaded with implication. They could imply that Smith had had opportunities for sexual relations with Pocahontas, either consensual or otherwise. On the other hand, since we can't assume the writing was done with extreme care and attention to implication, the words may simply be repeating the previous point, that he could have married Pocahontas regardless of who objected.

The passage continues:

- "Some that knewe not any thing to say, the Councel instructed, and advised what to sweare. So diligent they were in this businesse, that what any could remember, hee had ever done, or said in mirth, or passion, by some circumstantiall oath, it was applied to their fittest use, yet not past 8 or 9 could say much and that nothing but circumstances,10 which || all men did knowe was most false and untrue." Horn, p. 113

The lines "... what any could remember hee had ever done or said in mirth or passion by some circumstantiall oath ..." are also interesting and filled with implication. Townsend (2004, p. 75, 76) seems to read into them a kind of confession that Smith had sexually assaulted or abused Pocahontas. While I recognize that possibility, I also think we should consider these words with the presumed intent they were written, which was to defend Smith from allegations. They may be saying, "Hey, Smith joked about a lot of things like all soldiers do, but let's not take that too seriously" or something to that effect. They then say clearly that the accusations against Smith are false.

The passage continues with denials of any wrongdoing by Smith:

- "Many got their passes by promising in England to say much against him. I have presumed to say this much in his behalfe for that I never heard such foule slaunders, so certainely beleeved, and urged for truthes by many a hundred, that doe still not spare to spread them, say them and sweare them, that I thinke doe scarse know him though they meet him, nor have they ether cause or reason, but their wills, or zeale to rumor or opinion. For the honorable and better sort of our Virginian adventurers I think they understand it as I have writ it. For instead of accusing him, I have never heard any give him a better report, then many of those witnesses themselves that were sent only home to testifie against him." Horn, p. 113, 114

There is no mention of Pocahontas in these lines, but we are advised that all negative claims against Smith (including, presumably, those involving Pocahontas) were motivated by the desire of Smith's enemies in Jamestown to bring dishonor and disfavor upon him. With hindsight, we know this was to ensure that Smith never returned to Jamestown or had any further influence on the company or Jamestown affairs.

Letter to Queen Anne, 1616

The next mention of Pocahontas by John Smith comes in his letter to Queen Anne, which is problematic for its timing. The letter didn't see the light of day until its publication in Smith's The Generall Historie of 1624, though it is presumed to have been written in 1616 on the occasion of Pocahontas's coming to England. As the original copy of the letter has not been found (not unusual, actually) some people have doubts about it. Of course, there is no reason why it would have been published earlier (there was no Facebook in those days for publishing every occurring thought), but one has to leave open the very slight, but unlikely, possibility that the letter was written by Smith after the fact for the purpose of inserting himself into royal affairs in the public mind. Again, though, that seems extremely unlikely and there is no evidence for it. Slightly less unlikely, but still highly speculative, would be that Smith modified his draft of the letter before publishing it. Unfortunately, there is no way of knowing if that happened, so one has to rely on Smith's integrity as a historian. Personally, I have something like a 90% confidence in the letter as published, but I'm leaving open the possibility that it was modified in some way.

In any case, John Smith wrote more in this letter about his feelings for Pocahontas than in any other publication of his,. For the record, he also praised Nantaquaus, the presumed brother of Pocahontas, who he mentioned first as a person of "great courtesie" who was "the most manliest, comeliest, boldest spirit [Smith] ever saw in a Salvage". He continued, by writing:

Looking at these lines in isolation (i.e., without the additional context provided by what follows), we see that Smith evaluated Pocahontas as very compassionate and deserving of his respect, presumably for behavior that was not forthcoming from the other Indians he encountered. He could have been referring to her going to Jamestown with food for the settlers, or for her actions during his captivity at Werowocomoco. He continued with:

Here we see the clearest declaration of Pocahontas having saved his life and then going the extra mile to see him safely returned to Jamestown, or at least, this is how Smith interpreted the events. (We should note one clear inaccuracy, which is that Smith said he was prisoner for 6 weeks, when it was actually one month.) Smith acknowledges his debt to Pocahontas for his life and he also ascribes to Pocahontas his safe return to Jamestown instead of attributing his release to the good will of Powhatan.

A couple lines later, Smith continues:

Smith states here that the fledgling colony owed its continued existence to Pocahontas, who provided food even when the settlers were involved in intermittent skirmishing with the Powhatan Indians. Smith also gives Pocahontas the title of "Lady." which emphasizes her connection to nobility, presumably with the intent of gaining Queen Anne's sympathy.

The lines that follow are interesting:

Smith here offers three possible explanations for the extraordinary aide Pocahontas provided to the colony: 1) Pocahontas was an emissary of her father, or 2) she was God's instrument in His divine plan to maintain the colony, or 3) the aid was entirely owing to the personal good will and sacrifice of Pocahontas. While the first possibility is the most realistic one, it's interesting to me that Smith offers the two alternative explanations in the same breath, and they reveal Smith's gratitude for her actions, or at minimum his belief that these words would persuade Queen Anne of Pocahontas's merit to the colony.

Next, we see the second mention of the rescue in the woods in John Smith's writings:

As Smith had already referred to this incident in The Proceedings (1612), historians seem to accept this 'rescue' as having some basis in fact (in contrast to the legendary 'rescue' at Werowocomoco), though they are not necessarily on board with its significance as a rescue. Rountree, for example, wrote, "A warning to that effect from Pocahontas was completely unnecessary, but since it appears in two different accounts, {14} it could well have happened." from Pocahontas, Powhatan, Opechancanough (2005), p. 123. Rountree, with the benefit of hindsight, says the deed was "completely unnecessary," but we can't assume Pocahontas knew that, and it's not unreasonable to imagine that Smith would have appreciated the warning, considering the danger Pocahontas had faced in bringing him the message. In any case, Smith gives more significance to this 'rescue' than to the other more famous one, and he emphasizes the personal sacrifice Pocahontas performed for him and his soldiers.

The reference to Pocahontas's "watered eies [eyes]" is interesting. Smith is evoking desperation (and perhaps love) in her manner. Of course, this could have been an invention by Smith, but it's a hint at what he believed. Either that or a cynical effort to manipulate the Queen's emotions.

Smith's next lines repeat a point he has already made:

Smith was not much for self-editing, so he repeats the point about Pocahontas often coming to the colony with aid. Here he claims she was at Jamestown as often as she was at Werowocomoco, which we should construe as hyperbole. Smith points out that the continued success of the colony was due to Pocahontas, second only after God. This again emphasizes the high regard Smith held for Pocahontas, and indicates that he hoped the Queen would feel the same.

The lines that follow are:

Smith points out that in his and Pocahontas's absence, the colony descended into war with the Powhatans. However, when Pocahontas was captured and taken prisoner, peace returned to the colony, and she married an Englishman and became the first Powhatan Christian and had a child by an English man. The general facts, of course, would have been well known by the queen already, but Smith emphasizes them anyway, making sure to include his own critical role. Smith doesn't mention John Rolfe's name, which one might construe as a reluctance to elevate Rolfe's status in the drama, On the other hand, we see that Smith clearly understands the importance to the colony of the events he describes. We can't see evidence of Smith feeling regret that Pocahontas married someone else.

Smith next treats us to an impressively long sentence, the construction of which may have been an inspiration to writers like William Faulkner:

Under the apparent assumption that 'more words' equals 'more convincing,' Smith urges the queen to meet with Pocahontas, even if her husband (Rolfe) is not fit to attend with her, and even if Smith's own supplication is not worthy of the queen's attention. Smith then suggests an external threat, that if Pocahontas is not well received as she deserves to be, her negative reports to the Powhatans may result in their taking revenge on the colony, resulting in its failure.

Other than the mention of Pocahontas's virtue, want (need) and simplicity, we don't get any hints about Smith's feelings towards her here, We just know that Smith is going the extra mile to ensure Pocahontas's good reception by the queen, We have to assume, though, that the letter was actually delivered to the queen, and unfortunately, there is no evidence of that. I emphasize however, that we cannot assume there would be evidence.

Smith's letter to Queen Anne in its entirety at Encyclopedia Virginia

New England Trials (1622 re-print version)

In what appears to be the first mention* of the legendary Werowocomoco rescue of John Smith by Pocahontas, Smith writes:

When Smith credits someone with saving his life, it shouldn't be taken lightly. He describes Pocahontas as an instrument of God for freeing him from imprisonment by the Powhatans. This mention comes right after the Powhatan uprising of 1622, when anti-Powhatan sentiment was at a high, yet he chooses to portray Pocahontas as his rescuer.

* Note that when I say 'first mention', I mean first published mention, which would not include the 1616 letter to Queen Anne, which was not published until 1624.

The next mention of Pocahontas by John Smith comes in his letter to Queen Anne, which is problematic for its timing. The letter didn't see the light of day until its publication in Smith's The Generall Historie of 1624, though it is presumed to have been written in 1616 on the occasion of Pocahontas's coming to England. As the original copy of the letter has not been found (not unusual, actually) some people have doubts about it. Of course, there is no reason why it would have been published earlier (there was no Facebook in those days for publishing every occurring thought), but one has to leave open the very slight, but unlikely, possibility that the letter was written by Smith after the fact for the purpose of inserting himself into royal affairs in the public mind. Again, though, that seems extremely unlikely and there is no evidence for it. Slightly less unlikely, but still highly speculative, would be that Smith modified his draft of the letter before publishing it. Unfortunately, there is no way of knowing if that happened, so one has to rely on Smith's integrity as a historian. Personally, I have something like a 90% confidence in the letter as published, but I'm leaving open the possibility that it was modified in some way.

In any case, John Smith wrote more in this letter about his feelings for Pocahontas than in any other publication of his,. For the record, he also praised Nantaquaus, the presumed brother of Pocahontas, who he mentioned first as a person of "great courtesie" who was "the most manliest, comeliest, boldest spirit [Smith] ever saw in a Salvage". He continued, by writing:

- "... and his sister, Pocahontas, the Kings most deare and wel-beloved daughter, being but a child of twelve or thirteene yeers of age, whose compassionate pitifull heart, of my desperate estate, gave me much cause to respect her."

Looking at these lines in isolation (i.e., without the additional context provided by what follows), we see that Smith evaluated Pocahontas as very compassionate and deserving of his respect, presumably for behavior that was not forthcoming from the other Indians he encountered. He could have been referring to her going to Jamestown with food for the settlers, or for her actions during his captivity at Werowocomoco. He continued with:

- "I being the first Christian this proud King and his grim attendants ever saw: and thus inthralled in their barbarous power, I cannot say I felt the least occasion of want that was in the power of those my mortall foes to prevent, notwithstanding al their threats. After some six weeks fatting amongst those Salvage Courtiers, at the minute of my execution, she hazarded the beating out of her owne braines to save mine, and not onely that, but so prevailed with her father, that I was safely conducted to James towne ..."

Here we see the clearest declaration of Pocahontas having saved his life and then going the extra mile to see him safely returned to Jamestown, or at least, this is how Smith interpreted the events. (We should note one clear inaccuracy, which is that Smith said he was prisoner for 6 weeks, when it was actually one month.) Smith acknowledges his debt to Pocahontas for his life and he also ascribes to Pocahontas his safe return to Jamestown instead of attributing his release to the good will of Powhatan.

A couple lines later, Smith continues:

- "... such was the weaknesse of this poore Commonwealth, as had the Salvages not fed us, we directly had starved.

And this reliefe, most gracious Queene, was commonly brought us by this Lady Pocahontas, notwithstanding all these passages when inconstant Fortune turned our peace to warre, this tender Virgin would still not spare to dare to visit us, and by her our jarres have beene oft appeased, and our wants still supplyed; ..."

Smith states here that the fledgling colony owed its continued existence to Pocahontas, who provided food even when the settlers were involved in intermittent skirmishing with the Powhatan Indians. Smith also gives Pocahontas the title of "Lady." which emphasizes her connection to nobility, presumably with the intent of gaining Queen Anne's sympathy.

The lines that follow are interesting:

- "...were it the policie of her father thus to imploy her, or the ordinance of God thus to make her his instrument, or her extraordinarie affection to our Nation, I know not: ...

Smith here offers three possible explanations for the extraordinary aide Pocahontas provided to the colony: 1) Pocahontas was an emissary of her father, or 2) she was God's instrument in His divine plan to maintain the colony, or 3) the aid was entirely owing to the personal good will and sacrifice of Pocahontas. While the first possibility is the most realistic one, it's interesting to me that Smith offers the two alternative explanations in the same breath, and they reveal Smith's gratitude for her actions, or at minimum his belief that these words would persuade Queen Anne of Pocahontas's merit to the colony.

Next, we see the second mention of the rescue in the woods in John Smith's writings:

- "...but of this I am sure; when her father with the utmost of his policie and power, sought to surprize mee, having but eighteene with mee, the darke night could not affright her from comming through the irkesome woods, and with watered eies gave me intelligence, with her best advice to escape his furie; which had hee knowne, hee had surely slaine her. "

As Smith had already referred to this incident in The Proceedings (1612), historians seem to accept this 'rescue' as having some basis in fact (in contrast to the legendary 'rescue' at Werowocomoco), though they are not necessarily on board with its significance as a rescue. Rountree, for example, wrote, "A warning to that effect from Pocahontas was completely unnecessary, but since it appears in two different accounts, {14} it could well have happened." from Pocahontas, Powhatan, Opechancanough (2005), p. 123. Rountree, with the benefit of hindsight, says the deed was "completely unnecessary," but we can't assume Pocahontas knew that, and it's not unreasonable to imagine that Smith would have appreciated the warning, considering the danger Pocahontas had faced in bringing him the message. In any case, Smith gives more significance to this 'rescue' than to the other more famous one, and he emphasizes the personal sacrifice Pocahontas performed for him and his soldiers.

The reference to Pocahontas's "watered eies [eyes]" is interesting. Smith is evoking desperation (and perhaps love) in her manner. Of course, this could have been an invention by Smith, but it's a hint at what he believed. Either that or a cynical effort to manipulate the Queen's emotions.

Smith's next lines repeat a point he has already made:

- "James towne with her wild traine she as freely frequented, as her fathers habitation; and during the time of two or three yeeres, she next under God, was still the instrument to preserve this Colonie from death, famine and utter confusion, which if in those times, had once beene dissolved, Virginia might have line as it was at our first arrivall to this day."

Smith was not much for self-editing, so he repeats the point about Pocahontas often coming to the colony with aid. Here he claims she was at Jamestown as often as she was at Werowocomoco, which we should construe as hyperbole. Smith points out that the continued success of the colony was due to Pocahontas, second only after God. This again emphasizes the high regard Smith held for Pocahontas, and indicates that he hoped the Queen would feel the same.

The lines that follow are:

- "Since then, this businesse having beene turned and varied by many accidents from that I left it at: it is most certaine, after a long and troublesome warre after my departure, betwixt her father and our Colonie, all which time shee was not heard of, about two yeeres after shee her selfe was taken prisoner, being so detained neere two yeeres longer, the Colonie by that meanes was relieved, peace concluded, and at last rejecting her barbarous condition, was maried to an English Gentleman, with whom at this present she is in England; the first Christian ever of that Nation, the first Virginian ever spake English, or had a childe in mariage by an Englishman, a matter surely, if my meaning bee truly considered and well understood, worthy a Princes understanding."

Smith points out that in his and Pocahontas's absence, the colony descended into war with the Powhatans. However, when Pocahontas was captured and taken prisoner, peace returned to the colony, and she married an Englishman and became the first Powhatan Christian and had a child by an English man. The general facts, of course, would have been well known by the queen already, but Smith emphasizes them anyway, making sure to include his own critical role. Smith doesn't mention John Rolfe's name, which one might construe as a reluctance to elevate Rolfe's status in the drama, On the other hand, we see that Smith clearly understands the importance to the colony of the events he describes. We can't see evidence of Smith feeling regret that Pocahontas married someone else.

Smith next treats us to an impressively long sentence, the construction of which may have been an inspiration to writers like William Faulkner:

- "Thus most gracious Lady, I have related to your Majestie, what at your best leasure our approved Histories will account you at large, and done in the time of your Majesties life, and however this might bee presented you from a more worthy pen, it cannot from a more honest heart, as yet I never begged any thing of the state, or any, and it is my want of abilitie and her exceeding desert, your birth, meanes and authoritie, hir birth, vertue, want and simplicitie, doth make mee thus bold, humbly to beseech your Majestie to take this knowledge of her, though it be from one so unworthy to be the reporter, as my selfe, her husbands estate not being able to make her fit to attend your Majestie: the most and least I can doe, is to tell you this, because none so oft hath tried it as my selfe, and the rather being of so great a spirit, how ever her stature: if she should not be well received, seeing this Kingdome may rightly have a Kingdome by her meanes; her present love to us and Christianitie, might turne to such scorne and furie, as to divert all this good to the worst of evill, where finding so great a Queene should doe her some honour more than she can imagine, for being so kinde to your servants and subjects, would so ravish her with content, as endeare her dearest bloud to effect that, your Majestie and all the Kings honest subjects most earnestly desire: And so I humbly kisse your gracious hands."

Under the apparent assumption that 'more words' equals 'more convincing,' Smith urges the queen to meet with Pocahontas, even if her husband (Rolfe) is not fit to attend with her, and even if Smith's own supplication is not worthy of the queen's attention. Smith then suggests an external threat, that if Pocahontas is not well received as she deserves to be, her negative reports to the Powhatans may result in their taking revenge on the colony, resulting in its failure.

Other than the mention of Pocahontas's virtue, want (need) and simplicity, we don't get any hints about Smith's feelings towards her here, We just know that Smith is going the extra mile to ensure Pocahontas's good reception by the queen, We have to assume, though, that the letter was actually delivered to the queen, and unfortunately, there is no evidence of that. I emphasize however, that we cannot assume there would be evidence.

Smith's letter to Queen Anne in its entirety at Encyclopedia Virginia

New England Trials (1622 re-print version)

In what appears to be the first mention* of the legendary Werowocomoco rescue of John Smith by Pocahontas, Smith writes:

- "It is true in our greatest extremetie they shot me, slue three of my men, and by the folly of them that fled tooke me prisoner; yet God made Pocahontas the Kings daughter the meanes to deliver me: and thereby taught me to know their trecheries to preserve the rest."

When Smith credits someone with saving his life, it shouldn't be taken lightly. He describes Pocahontas as an instrument of God for freeing him from imprisonment by the Powhatans. This mention comes right after the Powhatan uprising of 1622, when anti-Powhatan sentiment was at a high, yet he chooses to portray Pocahontas as his rescuer.

* Note that when I say 'first mention', I mean first published mention, which would not include the 1616 letter to Queen Anne, which was not published until 1624.

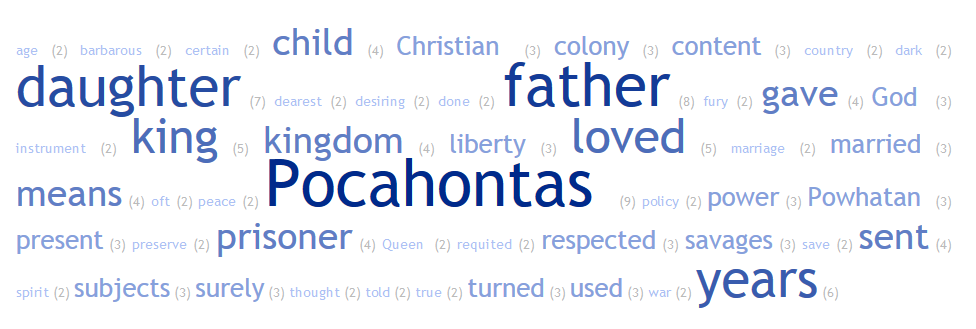

Word frequency list of the above references (with modernized spelling and deletion of non-relevant text)

The General Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles, 1624

Continuing now with mentions of Pocahontas in John Smith's writings, we get to The General Historie (1624), which represents Smith's effort to compile a complete account of English colonization in the New World and cement his legacy in English lore. It contains many references to Pocahontas, but it repeats most of the previous references above, and often with new or differing information. Smith also copies and pastes the accounts of others, such as Hamor, which makes it difficult to separate his own point of view from the authors he copies. It's further problematic because it comes some 15 years after the actual encounters and about 7 years after the death of Pocahontas. On one hand, you could consider it more reflective and showing a willingness to provide additional details, including information somewhat embarrassing to the author. On the other hand, we could say the details had likely become hazy in his mind, and the book may partially be an attempt to foster his own legend. In Smith's era, the line between 'history' and 'fiction' was not so carefully drawn in books of this type, If we apply 21st Century notions of what we should expect from a memoir, we are likely to be disappointed by its standard of historical rigor. Anyway, despite this duplicating much of what has already been said by Smith about Pocahontas, I will list the mentions of her in The General Historie, including some attributed to other authors. (Link to the complete text of The Generall Historie at the Univ. of North Carolina Library)

The first mention of Pocahontas in The Generall Historie comes in the dedication page (called Epistle Dedicatory in the Pocahontas Archive) to Lady Francis, Duchesse of Richmond and Lennox.

- "In the utmost of many extremities, that blessed Pokahontas, the great Kings daughter of Virginia, oft saved my life." from Horn (2007), p. 203

Some early mentions of Pocahontas in The Generall Historie are usually ignored today, probably because they appear in the table of contents and lack exposition. They are as follows (with non-relevant entries deleted):

- "The third Booke.

Of the Accidents and Proceedings of the English.

1607 ... Captaine Smith taken prisoner; their order of Triumph, and how he should have been executed, was preserved, saved James towne from being surprised, how they Conjured him;. Powhatan entertained him, would have slaine him; how Pocahontas his daughter saved him, and sent him to James Towne. ....

1608 ...Captaine Smith visiteth Powhatan; Pocahontas entertains him with a Maske; ...

Powhatan's plot to murther Smith, discovered by his daughter Pocahontas. from Horn (2007), p. 219, 220

The fourth Booke.

With their Proceedings after the alteration of the Government.

1612 ... how Captaine Argall tooke Pocahontas prisoner; ...

1613 ... the marriage of Pocahontas to Master Rolfe ...

1616 .Dale with Pocahontas comes for England....

A relation [letter] to Queene Anne of the quality and condition of Pocahontas

1617 how the Queen entertained her; ..." from Horn (2007), p. 221

Not mentioned in the table of contents are the visits by Pocahontas to Jamestown, Smith's visit with Pocahontas in England, or her death and burial at Gravesend.

So can we glean any useful information from these entries? Not much. It's interesting that Smith has en entry in the table of contents for the death of Powhatan (in the 'fourthe Booke', but not one for Pocahontas.

The next mention of Pocahontas is a copy and paste repeat from what he wrote in A Map of Virginia re. what appears to be an example language exchange with Pocahontas. As in A Map of Virginia, it comes after a glossary of Powhatan words and expressions.

- "Kekaten Pokahontas patiaquagh niugh tanks manotyens neer mowchick rawrenock audowgh, Bid Pokahontas bring hither two little Baskets, and I will give her white Beads to make her a Chaine." from Horn (2007), p. 303

The next Smith mention of Pocahontas in The Generall Historie is probably the most famous and controversial one. While not the 'first mention' of the legendary rescue at Werowocomoco, it's the most detailed and compelling of all mentions.

- "Having feasted him after their best barbarous manner they could, a long consultation was held, but the conclusion was, two great stones were brought before Powhatan: then as many as could layd hands on him, dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs, to beate out his braines, Pocahontas the Kings dearest daughter, when no intreaty could prevaile, got his head in her armes, and laid her owne upon his to save him from death: whereat the Emperour was contented he should live to make him hatchets, and her bells, beads, and copper; for they thought him aswell of all occupations as themselves." from Horn (2007), p. 321.

By giving us the dramatic image of Pocahontas laying her head over his to prevent his death at the risk of her own, Smith ensured their permanent place in history and legend. The mention in 1622 states only "... God made Pocahontas the Kings daughter the meanes to deliver me ..." and the 1616/1624 letter to Queen Anne states "at the minute of my execution, she hazarded the beating out of her owne braines to save mine..." All of these statements describe the same event, but only the 1624 Generall Historie version offers up the skin-on-skin, head-on-head image that the world came to love.

So does this mention imply romance? The face-to-face contact may have suggested so. Smith states no age for Pocahontas in these lines, as he did in previous writings ("a child of tenne" in A True Relation (1608), and "not past 13 or 14 yeares of age" in The Proceedings (1612), so we're free to imagine her as a beautiful adult woman. On the other hand, readers at the time of publication would presumably already know some details about Pocahontas, including perhaps her young age. And Smith doesn't exactly build on the concept of a romance in subsequent mentions, as we'll see. The attractiveness of the scene may just as likely have been the image of a young child saving the life of the hardened English soldier, Smith. And since many ethnohistorians now consider this act by Pocahontas to be part of a role she played in an adoption ceremony, we must give some weight to the possibility that Pocahontas had no choice in the matter, i.e., she placed her head on Smith's at the behest of others (if, in fact it happened at all).

After Smith's return to Jamestown, Pocahontas apparently made repeated appearances:

- "Now ever once in foure or five dayes, Pocahontas with her attendants, brought him so much provision, that saved many of their lives, that els for all this had starved with hunger." from Horn (2007), p. 322.

This is the third mention in Smith's writings (after The Proceedings and 'Letter to Queen Anne') of Pocahontas coming to Jamestown regularly with provisions for the starving colonists. Smith words it as her coming with provisions for 'him', i.e., Smith himself to distribute among the colonists. This may be boastful on Smith's part, but it may also be possible that Powhatan had made the instruction that Smith was the point of contact, since he was the one who had (presumably) been adopted into the Powhatan confederation. Note also that Smith describes the visits as 'Pocahontas with her attendants," though it may more reasonably have been described as 'Powhatan's warriors-messengers with Pocahontas along as a symbol of peaceful intentions. It should also be mentioned that Smith first told of Powhatan providing food to the colonists (in A True Relation) with no mention of Pocahontas at all.

Another mention soon follows:

- "His relation of the plenty he had seene, especially at Werawocomco, and of the state and bountie of Powhatan, (which till that time was unknowne) so revived their dead spirits (especially the love of Pocahontas) as all mens feare was abandoned." Horn (2007), p. 323.

Smith had just previously mentioned how Pocahontas came with provisions, and while his use of the word 'love' here,is somewhat ambiguous, I believe it refers to her compassion, mainly for Smith during the rescue at Werowocomoco, but perhaps also for the colonists for whom the provisions are provided.

- "To whom the Salvages, as is sayd, every other day repaired, with such provisions that sufficiently did serve them from hand to mouth: part alwayes they brought him as Presents from their Kings, or Pocahontas;" Horn (2007), p. 324.

Smith is again referring to the provisions generously provided by Powhatan, his sub-chiefs, and Pocahontas. The influence Pocahontas had on the matter of providing provisions seems doubtful to me, but I suppose we'll never know for sure. In any case, Smith wants to give her a share of the credit. She was the one who was there after all, not Powhatan.

The next mention of Pocahontas is a repetition from earlier writings, the mission sent by Powhatan to obtain the release of imprisoned warriors::

- " ... yet he [Powhatan] sent his messengers, and his dearest daughter Pocahontas with presents to excuse him of the injuries done by some rash untoward Captaines his subjects, desiring their liberties for this time, with the assurance of his love for ever. After Smith had given the prisoners what correction he thought fit, used them well a day or two after, and then delivered them Pocahontas, for whose sake onely he fayned to have saved their lives, and gave them libertie." Horn (2007) p. 331

As in The Proceedings, the name Rawhunt is absent from this version, though we know from previous writings that he is among the messengers. Instead, Smith once again makes Pocahontas the central negotiator here, which was almost certainly not the case. We should note that the word 'love' refers to the love of Powhatan. When people look for romance in Smith's writings, we must remember that the world 'love' has a broader meaning than romantic love, and Smith uses it like we might use the word 'compassion'. When Smith includes the phrase "... for whose sake onely he fayned to have saved their lives", Smith is probably trying to portray himself as an able negotiator, but to the modern reader it makes him sound deceptive and insincere. Nevertheless, the reference to Pocahontas has the effect of elevating her in these types of interactions.

Smith seems legitimately appreciative of Pocahontas, as he repeats yet again that she came often with provisions for the colonists. In this case, Smith also acknowledges the chiefs who were involved in some way in the supplying of food:

- "But Newport got in and arrived at James Towne, not long after the redemption of Captaine Smith. To whom the Salvages, as is sayd, every other day repaired, with such provisions that sufficiently did serve them from hand to mouth: part alwayes they brought him as Presents from their Kings, or Pocahontas;" Horn (2007) p. 324

The next mention of Pocahontas in The Generall Historie is another one of those situations (like the rescue) where Smith inserts Pocahontas into a story where she had previously been absent. This obviously raises some red flags: The first paragraph below and the phrase in bold were added to a nearly identical story from The Proceedings:

- "Powhatan being 30 myles of, was presently sent for: in the meane time, Pocahontas and her women entertained Captaine Smith in this manner.