- Home

- History

-

Controversies

- Controversies

- Is John Smith's account of his rescue by Pocahontas true?

- Did John Smith misunderstand a Powhatan 'adoption ceremony'?

- What was the relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith?

- Is it possible that John Smith never actually met Pocahontas?

- Was Smith's gunpowder accident actually a murder plot?

- How should we view John Smith's credibility overall?

- How was Pocahontas captured?

- Did Pocahontas willingly convert to Christianity?

- What should we make of Smith's "rescues" by so many women?

- Were Pocahontas and John Rolfe in love?

- What was the meaning of Pocahontas's final talk with John Smith?

- How did Pocahontas die?

- How did John Rolfe die?

- Was there a Powhatan prophecy?

- Why didnt the Indians wipe out the settlers?

- When did the balance of power shift from the Powhatans to the English?

- How big a part did European diseases play in the Jamestown story?

- Books

- Art

- Films

- Powhatan Tribes

- Links

- Site Map

- Contact

Portraits

Pocahontas lived in an era before photography and where only the wealthy and influential could commission a painted portrait. There were no portrait artists in Jamestown, so we have no idea what Wahunsenaca or Opechancanough or many of the colonists looked like. We don't know what John Rolfe or Thomas Rolfe looked like either. Nevertheless, we are fortunate to have a single image of Pocahontas in existence that was done during her lifetime, though many people who see it come away slightly disappointed. Some writers have stated that Pocahontas was already ill at the time of the sitting, but that seems to be mainly in reaction to the image, as no one wrote of her being ill at the time. But we do have that one image, and like Pocahontas herself, it has been a source of speculation and story telling. In the paragraphs below, I'll explain what we know about the portrait and its spinoffs.

|

The Simon van de Passe engraving

The 1616 image at right is the only representation of Pocahontas made in her lifetime. It is believed that Simon van de Passe (1595-1647), the Dutch engraver, sketched her likeness in an actual sitting, then created the engraving for the Virginia Company to use in their publicity campaign. This is the closest we'll ever get to knowing what Pocahontas looked like. Interestingly, de Passe is also our source for the likeness of John Smith. The clothes that Pocahontas is wearing in the portrait are meant to show how well integrated she was into English life in order to reassure investors that the natives could be made to adopt English ways. The beaver hat is light in color, presumably white, gray or tan. The feather fan is said to be symbolic with various interpretations, but we can see many such fans in portraits of the era. The names Matoaka (often said to be her real Indian name but likely a Latinization) and Rebecca (her Christian name) appear in the border. Husband John Rolfe's name is also mentioned (Joh. Rolff). This portrait is our source for Pocahontas's age and by calculation, her approximate birth date. According to Rasmussen & Tilton (1994), in Pocahontas: Her Life & Legend, artist Simon van de Passe was the son of Crispin van de Passe the elder, a portraitist to the English court.. Simon aimed to follow in his father's footsteps (p. 32). More on the Simon van de Passe Engraving |

Camilla Townsend, in the Smithsonian Channel's 2017 Pocahontas: Beyond the Myth

* Camilla Townsend has since clarified that the word 'brochure' should have been 'broadside,' which was usually a single sheet of paper used for advertising purposes. Merriam-Webster says, "1. a sizable sheet of paper printed on one side" and "2. a sheet printed on one or both sides and folded". - edit 5/24/2021

- "Simon van de Passe, an artist at the time, was asked by the Virginia Company to sketch her and then make an engraving for a brochure."

Narrator: "It's the only picture of her made from life."

Townsend: "It is noteworthy that he did not at that time attempt to make her look like your average white English girl or German girl or French girl, right? She is very clearly in that image a native American person."

* Camilla Townsend has since clarified that the word 'brochure' should have been 'broadside,' which was usually a single sheet of paper used for advertising purposes. Merriam-Webster says, "1. a sizable sheet of paper printed on one side" and "2. a sheet printed on one or both sides and folded". - edit 5/24/2021

|

Copy of Van de Passe engraving made over 150 years later

The 1793 image at right is a copy by an unknown artist of the van de Passe engraving (Source: Rasmussen, Tilton 1994). In this image, Pocahontas has a slightly more European look, as her cheekbones are less clearly defined, and she has rounder eyes. This was a subtle attempt at making Pocahontas appear less 'ethnic.' The easiest way to distinguish between the two engravings is by looking at the backgrounds (curved lines in the original; straight lines in the copy). The replica also places dots inside the O, C and G of the border writing. To the casual observer, there may be no significant difference between the reproduction and the original, but to preserve historic authenticity, we should try to keep them apart. This seems to be difficult, as even museum websites, such as that of the Virginia Museum of History and Culture are apt to confuse them. Notice they use the 1793 reproduction on their Pocahontas page while speaking of the "only life portrait.' (March 21, 2018) The original Simon van de Passe and the reproduction are often attributed to the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., but in fact there are copies of both elsewhere. The images are engravings, so they were meant to be printed on a mass scale. |

The Booton Hall Portrait

Booton Hall Portrait Booton Hall Portrait

|

The Booton Hall Portrait was painted by an unidentified artist, modeled after the Simon van de Passe engraving and some time after the engraving had been published. The portrait has been described by some as being the original upon which Simon van de Passe based his engraving, but that theory is currently not in favor. The painting can only be traced back to the mid-1700s, so there is no evidence it was painted during Pocahontas's lifetime.

Philip L. Barbour, in Pocahontas and Her World (1971), wrote “A European portrait-painter of 1616-1617 would surely have noticed that Pocahontas was 'brown’ or 'tawny,’ like the rest of her people. But the color of her skin in the portrait is clearly European, and her hair is a European brown, not an Indian black. Relying only on the engraving, a painter-copyist would not have recognized his own error.” (from Wikimedia Commons). In the same vein, the beaver hat is shown as black, while the engraving appears light in color (white or tan). This is another mistake a painter-copyist could have made, but not the original artist/engraver or a hypothetical copyist/engraver. John Chamberlain (1553-1628), after seeing a copy of the engraving that was widely published, wrote in a letter, "Here is a fine picture of no fayre Lady." It is believed Chamberlain was referencing the engraving and not the painting in order to make such a comment. |

Author comments that muddy the record

From Savage Kingdom (2007) by Benjamin Woolley

"... to advertise Pocahontas's presence there [in England], the Virginia Company commissioned a portrait. An obscure and therefore relatively cheap Dutch artist called Simon Van de Passe was hired to perform the task. The result was an awkward, probably rushed affair. It showed her dressed in expensively embroidered English dress, her face framed by a huge starched ruff and feathered high hat. Perhaps the most noticeable feature of an undistinguished work was that she clutched a fan of three white feathers, the insignia of the Prince of Wales, evidently included as a homage to Prince Henry's influence over the venture. The engraving printed up for mass circulation was even less flattering." p. 332.

From A Man Most Driven (2014) by Peter Firstbrook

"During her visit, Pocahontas also had her portrait painted, and then engraved by Simon van de Passe, the same Dutch artisan who caught Smith's likeness for the Map of Virginia. The painting now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC." p. 334

My comment on Woolley & Firstbrook;

Both Woolley and Firstbrook seem to think an oil painting, possibly the Booton Hall Portrait (above) was the original, and that it was painted by Simon van de Passe before he made the engraving. This is incorrect. They both also say the oil painting is in the National Portrait Gallery, which further points to the Booton Hall Portrait, or a replica of the Booton Hall Portrait. There are several versions of the engraving and painting in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., however, and it's sometimes difficult to know which version authors are talking about when they say it "hangs in the National Portrait Gallery." (There is also this to complicate matters further, as it cannot be found on the National Portrait Gallery website, so its provenance and current whereabouts are unknown.)

And a corrective ...

From Pocahontas, Powhatan and Opechancanough (2005) by Helen Rountree

"One of the things that passed the time [at Brentford] was that Pocahontas had her portrait done. It was not a painting, for that would require too much time (and money). Instead the engraver Simon van de Passe, who would later create a portrait of John Smith, made a sketch of her and then produced engravings from it that were circulated to interested parties. ... That engraving was the only portrait of her done from life, so it is unfortunate that van de Passe was no expert at depicting an Amerind face with epicanthic folds over the eyes. Artists in later centuries largely ignored that picture and painted their own, even paler, more Europeanized 'princess.'" p. 180.

My comment on Rountree:

Rountree, unlike Woolley and Firstbrook, does not think that the Booton Hall Portrait is the original, and I agree. We're with Philip Barbour and others on this. The Simon van de Passe engraving should be considered the original and most definitive image. Rountree says that the engraving was "largely ignored" by later artists, but the Booton Hall Portrait is a notable exception.

From Savage Kingdom (2007) by Benjamin Woolley

"... to advertise Pocahontas's presence there [in England], the Virginia Company commissioned a portrait. An obscure and therefore relatively cheap Dutch artist called Simon Van de Passe was hired to perform the task. The result was an awkward, probably rushed affair. It showed her dressed in expensively embroidered English dress, her face framed by a huge starched ruff and feathered high hat. Perhaps the most noticeable feature of an undistinguished work was that she clutched a fan of three white feathers, the insignia of the Prince of Wales, evidently included as a homage to Prince Henry's influence over the venture. The engraving printed up for mass circulation was even less flattering." p. 332.

From A Man Most Driven (2014) by Peter Firstbrook

"During her visit, Pocahontas also had her portrait painted, and then engraved by Simon van de Passe, the same Dutch artisan who caught Smith's likeness for the Map of Virginia. The painting now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC." p. 334

My comment on Woolley & Firstbrook;

Both Woolley and Firstbrook seem to think an oil painting, possibly the Booton Hall Portrait (above) was the original, and that it was painted by Simon van de Passe before he made the engraving. This is incorrect. They both also say the oil painting is in the National Portrait Gallery, which further points to the Booton Hall Portrait, or a replica of the Booton Hall Portrait. There are several versions of the engraving and painting in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., however, and it's sometimes difficult to know which version authors are talking about when they say it "hangs in the National Portrait Gallery." (There is also this to complicate matters further, as it cannot be found on the National Portrait Gallery website, so its provenance and current whereabouts are unknown.)

And a corrective ...

From Pocahontas, Powhatan and Opechancanough (2005) by Helen Rountree

"One of the things that passed the time [at Brentford] was that Pocahontas had her portrait done. It was not a painting, for that would require too much time (and money). Instead the engraver Simon van de Passe, who would later create a portrait of John Smith, made a sketch of her and then produced engravings from it that were circulated to interested parties. ... That engraving was the only portrait of her done from life, so it is unfortunate that van de Passe was no expert at depicting an Amerind face with epicanthic folds over the eyes. Artists in later centuries largely ignored that picture and painted their own, even paler, more Europeanized 'princess.'" p. 180.

My comment on Rountree:

Rountree, unlike Woolley and Firstbrook, does not think that the Booton Hall Portrait is the original, and I agree. We're with Philip Barbour and others on this. The Simon van de Passe engraving should be considered the original and most definitive image. Rountree says that the engraving was "largely ignored" by later artists, but the Booton Hall Portrait is a notable exception.

Essay on the Simon van de Passe engraving from The Pocahontas Archive, by Edward J. Gallagher. Note that the image appearing on this webpage is the 1793 replica, not the original!

In researching the Simon van de Passe engraving and its related painting, the Booton Hall Portrait, I wondered how we actually know which of the two came first. It is generally accepted that the Simon van de Passe engraving is the original, as I've indicated above (via Rountree 2005), but how do we know for sure? Do the historical records of the Virginia Company actually state that Simon van de Passe was commissioned to make a Pocahontas portrait? As far as I can tell, there is no reference in the Virginia Company documents that mention hiring de Passe (but I say that only because no authors in my research have referenced it). Researchers have made some (reasonable) assumptions based on a few facts that strongly suggest the Simon van de Passe engraving is the real original. However, we do not have 100% certainty. I welcome any information from readers that can help settle the matter.

Reasons why we believe the Simon van de Passe engraving is the original:

An interesting (if unconvincing) defense of the Booton Hall Portrait as the original came from a Francis Burton Harrison, who wrote (circa 1926?), "In the end, therefore, the authenticity of the portrait rests largely on the fact, which is a convincing fact, that it is the palpable original from which DePasse engraved the cruel caricature which ever since her death has passed current as the likeness of Pocahontas, a caricature reproduced again and again to illustrate the little maiden's romantic story .. To bring home this identification and criticism, it is only necessary to compare the photographs recently made from the original portrait and from an example of the DePasse print ...." In other words, the painting must be the original because it's more attractive! (from "The Pocahontas Portrait" (1927).

Reasons why we believe the Simon van de Passe engraving is the original:

- Simon van de Passe was verifiably living and active during Pocahontas's lifetime. He also made the John Smith engraving, which is the only contemporary image of Smith. (Firstbrook, p. 300)

- The Booton Hall portrait can only be traced back to the mid-1700s.

- An engraving would have been more within the budget of the Virginia Company at the time and more useful for reproduction.

- The Booton Hall portrait is different in ways that indicate it came later, not before (coloring of skin, hair & hat).

- Because the Simon van de Passe engraving was considered unflattering by some (perhaps, according to Rountree, because the artist was not used to depicting Native American faces), the Booton Hall Portrait may have been an attempt to re-make her image and render her more attractive and conform to romanticized European expectations..

- Letter writer John Chamberlain (1553-1628) made a contemporary reference to a presumed copy of the engraving.

- The Booton Hall portrait erroneously makes reference to Pocahontas's husband as Tho. Rolfe, which one presumes the original artist would not do. However, this mistake has been attributed to a later addition to the painting after it was damaged by fire, and the restorer misread the letters Joh and changed them to Tho. (from "The Pocahontas Portrait" in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 35, Nov. 4 (Oct. 1927).

An interesting (if unconvincing) defense of the Booton Hall Portrait as the original came from a Francis Burton Harrison, who wrote (circa 1926?), "In the end, therefore, the authenticity of the portrait rests largely on the fact, which is a convincing fact, that it is the palpable original from which DePasse engraved the cruel caricature which ever since her death has passed current as the likeness of Pocahontas, a caricature reproduced again and again to illustrate the little maiden's romantic story .. To bring home this identification and criticism, it is only necessary to compare the photographs recently made from the original portrait and from an example of the DePasse print ...." In other words, the painting must be the original because it's more attractive! (from "The Pocahontas Portrait" (1927).

Essay about the Simon Van de Passe engraving and the Booton Hall Portrait at the U.S. Govt. Publishing Office/Catalogue of Fine Art

|

Pocahontas (1889-1907) by Richard Norris Brooke This full-length portrait is in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, VA. It is an imaginative, white-washed rendering based on the Van de Passe engraving, much like the Booton Hall portrait above.

The plaque at the museum said this in 2016: Richard Norris Brooke American, 1847-1920 Pocahontas, 1889 and 1907 Oil on canvas GIft of John Barton Payne, 19.1.51 "In 1889, the year that the Oklahoma "land run" catapulted homesteaders into the last open territory of the American West, Brooke began his life-size image of one of the country's most famous Native Americans--Pocahontas. The Virginia-born painter chose as his source an adaptation of a 1616 life portrait of the Powhatan woman, but quickly abandoned his work, claiming that 'the court costume on an Indian type was not pleasing.' Eighteen years later, the Colonial Revival fervor surrounding the three-hundredth anniversary of the English landfall at Jamestown prompted him to finish the painting in time for the exposition in Norfolk. Brooke ultimately addressed the earlier difficulties by anglicizing his version of the Virginia princess. His final Pocahontas is a fair-skinned figure who turns to meet the viewer with a confident gaze." |

|

The Mary Ellen Howe (1994) Replica

The 1994 Mary Ellen Howe portrait of Pocahontas tries to correct the mistakes in the Booton Hall Portrait and preserves the (presumed) authenticity of the Simon van de Passe engraving. This portrait is in the Virginia Museum of History in Richmond, Va. and graces the cover of both Townsend's Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma (2004) and Rountree's Pocahontas, Powhatan & Opechancanough (2005) . Note the darker skin than in the Booton Hall portrait the black hair, and the white beaver hat.

Rasmussen & Tilton (1994), in Pocahontas: Her Life & Legend, record that Howe visited and researched the Pamunkey, Mattaponi and Rappahannock Indians of Virginia to better approximate skin color. She noticed the overbite, dimpled chin and high cheek bones from the portrait among Indians living in Virginia today (p 49). I don't know if gossip John Chamberlain would have liked this portrait any more than the engraving, but for us today, it provides an image that is better than any other we have of the real Pocahontas. Rasmussen and Tilton describe it as "the most accurate portrait of Pocahontas that has been or can be painted." p. 49. Edit 12/18/2019 - I plan to write in more detail about this portrait, but for now, I'd just like to add two thoughts: 1) the notion that Howe could glean any useful information about Pocahontas's skin color from current Powhatan residents is questionable, and 2) the beaver hat would likely not have been white. See 'More on the Van de Passe engraving' |

|

The New World (2005) film version

The New World costume designers did a nice job of capturing the general feel of the attire from the portrait, but we notice right away that they didn't try to duplicate it exactly. The color of the hat is wrong, for one, We have to admit, the black hat here is attractive, though, and the real human face of the actress helps us to understand how an engraving and photo necessarily differ. Obviously, the half-Peruvian, half Swiss-German actress (Q'orianka Waira Qoiana Kilcher) is unlikely to resemble the real Pocahontas, though we'll never know for sure. Note that this movie prop hat is not an actual beaver hat, but a fabric copy. See 'More on the Van de Passe engraving' |

Not Pocahontas!

|

The Sedgeford Hall Portrait

The Sedgeford Hall Portrait has an interesting history, and for many years, it was thought to be a portrait from life of Pocahontas and her son, Thomas Rolfe. This turned out to be wishful thinking on the part of the Rolfe family in England, who purchased the painting based on that mistaken belief. The painting is actually of Pe-o-ka, the wife of Seminole Chief, Osceola, and their son. The portrait is on display in King's Lynn Town Hall, Norfolk, UK. A sign posted under the portrait reads, "The mother and child portrayed are probably Pe-o-ka, the wife of Osceola, the War Chief of the Seminoles of Florida, and their child in 1837. It was acquired by Eustace Neville Rolfe of Heacham Hall who believed it represented Pocahontas and her son." Many books and websites on Pocahontas still feature this image, claiming it to be Pocahontas and Thomas Rolfe. Don't be fooled! New article on the history of the Sedgeford Hall Portrait. "Is the Sedgeford Hall Portrait Evidence of a Crime?" |

The following books (among others) all misidentified the woman in the Sedgeford Hall Portrait as Pocahontas. At the time these books were published, there was some doubt* about the age of the portrait by art historians, but generally, people accepted the popular identification, as no precise alternative information existed. The subjects were finally identified as Pe-o-ka and her son in 2010 by researcher Bill Ryan. Skepticism about the portrait is mentioned in Tilton's Pocahontas: the Evolution of an American Narrative (1994) p. 108. Note too that Mossiker's 1976 book, Pocahontas: the Life and the Legend, does not make this mistake. Mossiker's contemporaries must have thought of it as an omission, but she was actually correct not to mention it!

Edit (9/1/2020): Books about Pocahontas published in 2015 and 2017, well after the re-identification of the above portrait, still include it as an illustration of Pocahontas and Thomas. This is unacceptable.

Edit (9/1/2020): Books about Pocahontas published in 2015 and 2017, well after the re-identification of the above portrait, still include it as an illustration of Pocahontas and Thomas. This is unacceptable.

Additionally, Paula Gunn Allen, in Pocahontas: Medicine Woman, Spy, Entrepreneur, Diplomat (2003), appears to refer to Pocahontas being in the Sedgeford Hall Portrait, though she doesn't identify the portrait by name: “ … someone seems to have determined that the young couple should visit the ancestral Rolfe estate. … While they were there ... a portrait of Lady Rebecca and her son, Thomas, was made.” p. 294

|

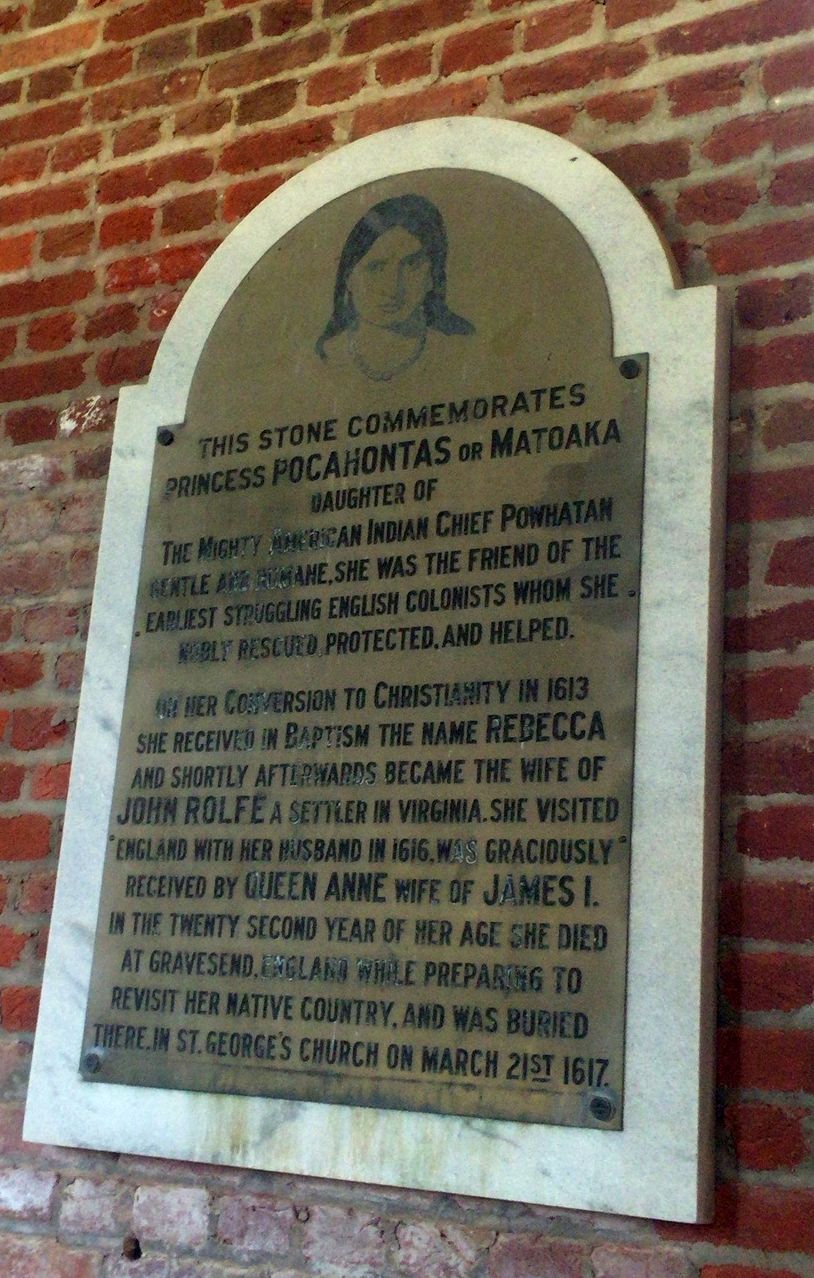

Erroneous Plaque at Historic Jamestowne

One might think that Historic Jamestowne would try to get the image of Pocahontas right, but as we see from the plaque inside the reconstructed church, the image of Pe-o-ka from the Sedgeford Hall Portrait is used to represent Pocahontas. The plaque makes no reference to the source of the image. It reads: "This stone commemorates princess Pocahontas or Matoaka, daughter of the mighty American Indian chief, Powhatan. Gentle and humane, she was the friend of the earliest struggling English colonists.whom she ably rescued, protected and helped. At her conversion to Christianity in 1613, she received in baptism the name Rebecca and shortly afterwards became the wife of John Rolfe, a settler in Virginia. She visited England with her husband in 1616, was graciously received by Queen Anne, wife of James I. In the twenty-second year of her age, she died at Gravesend, England, while preparing to revisit her native country, and was buried there in St. George's church.on March 21st, 1617." I suspect that the Historic Jamestowne museum would like to rectify the error, but the plaque has probably gained some historical value of its own, making it difficult to casually replace. |

Pictures of Pocahontas - Link to site Top Illustrations by Top Artists' Beautiful Public Domain Illustrations

(C) Kevin Miller 2018

Updated Oct. 31, 2021 / Banner photo by Hadley-Ives

Updated Oct. 31, 2021 / Banner photo by Hadley-Ives

- Home

- History

-

Controversies

- Controversies

- Is John Smith's account of his rescue by Pocahontas true?

- Did John Smith misunderstand a Powhatan 'adoption ceremony'?

- What was the relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith?

- Is it possible that John Smith never actually met Pocahontas?

- Was Smith's gunpowder accident actually a murder plot?

- How should we view John Smith's credibility overall?

- How was Pocahontas captured?

- Did Pocahontas willingly convert to Christianity?

- What should we make of Smith's "rescues" by so many women?

- Were Pocahontas and John Rolfe in love?

- What was the meaning of Pocahontas's final talk with John Smith?

- How did Pocahontas die?

- How did John Rolfe die?

- Was there a Powhatan prophecy?

- Why didnt the Indians wipe out the settlers?

- When did the balance of power shift from the Powhatans to the English?

- How big a part did European diseases play in the Jamestown story?

- Books

- Art

- Films

- Powhatan Tribes

- Links

- Site Map

- Contact